27th December 2017.

Every well traded market offers opportunity and danger. The opportunity is to buy low and sell high. The grave danger is that the investor/speculator does the opposite- sells at the bottom and buys at the top. The history of returns from equity markets reveals just how tempting it is to try and get the timing of entry into and exit from the market right; or, to put it more modestly, why it is important not to get the timing badly wrong.

The irregular pattern of past returns from equities

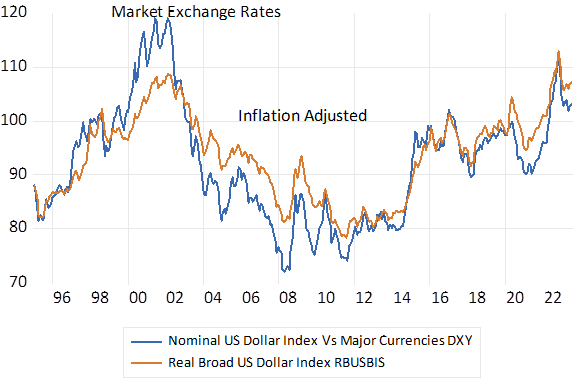

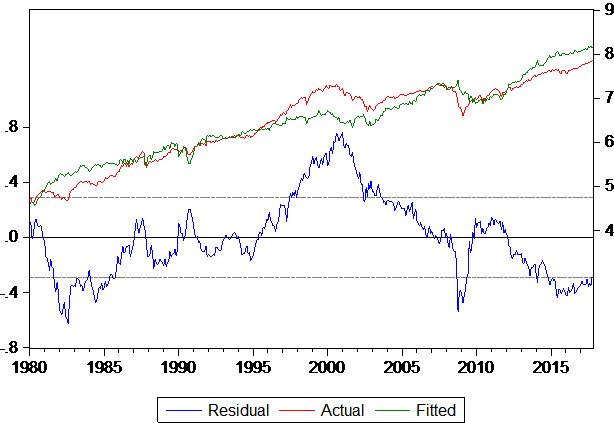

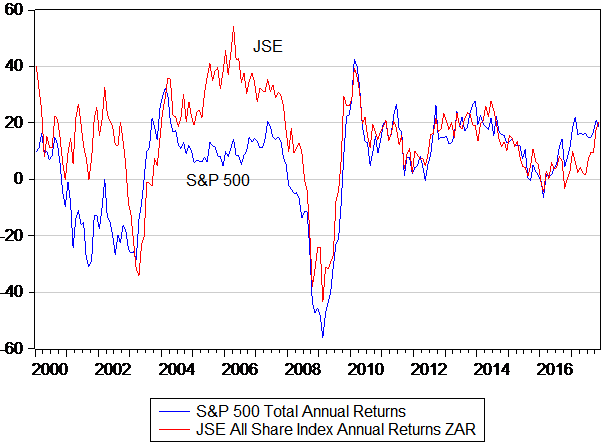

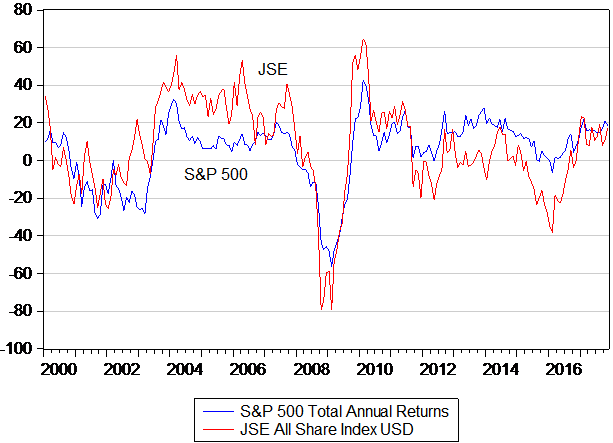

In figure 1 we show that since January 2000, the ups and downs of the S&P 500 Index of the largest companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange and the JSE All Share Index. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that getting out of the New York market in early 2000 and re-entering in 2002, would have been very good for wealth creation. For investors on the JSE, timing would have called for even greater agility. It would have been best to have sold off somewhat later, in 2002, and then to have re-entered in 2003, so benefiting from the excellent returns available until the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 caused so much damage to all equity markets.

Despite all the understandable gloom and doom of that unhappy episode in the history of capitalism, the GFC was followed by a period of strong and sustained value gains that continue to the present day (late 2017). It has been a rising equity tide that only briefly faltered in 2014. Those with strong beliefs in the essential strength of the global economic system and, more important, with faith in the capabilities of central bankers to come to the rescue, did well not to sell out in 2008 at what proved to be a deep bottom to share prices.

Figure 1: Annual returns on the S&P 500 Index (USD) and the JSE All Share Index (ZAR)

Source: Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment

These total share market returns (price changes and dividends received) have been calculated as gains or losses realised over the previous 12 months and calculated each month. The average annual return on the S&P 500 between January 2000 and November 2017, in US dollars, was 5.3% compared to 14.4% in rands generated on the JSE. The worst month for both markets was in late 2008, when both markets were down over 50% on the year before. The best year-on-year return on the S&P 500 over this period was 43%, realised in the 12 months to February 2010, while the best months for investors on the JSE were in late 2005 when annual returns peaked at over 50%. Adjusted for inflation in the US and SA, the S&P Index has provided about a real average 3% p.a return and the JSE an impressive 8% p.a. in real rands.

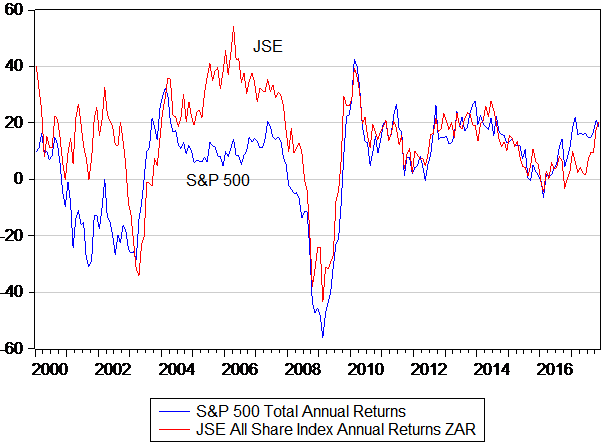

When measured in US dollars, the JSE also outperformed, having delivered close to 7.5 % p.a on average compared to the 5.3% p.a earned on the S&P 500. It may be seen in figure 2 below that the JSE provided superior US dollar returns between 2003 and 2007, but offered markedly inferior returns (in US dollars) compared to the S&P 500 since 2012. These high average returns over an extended period of time surely indicate the advantage of maintaining consistently high exposure to equities over the long run.

Figure 2: annual US dollar returns – S&P 500 Index and the JSE All Share Index

Source: Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment

While timing which market to favour over another – the JSE before 2008 and the S&P 500 after 2014 – can make an important difference to investment outcomes, it should also be noted that the returns on the S&P 500 and the JSE are quite highly correlated on average (close to 70%) in all the ways to measure performance.

The forces common to all equity markets around the world will often be directed from the US economy and its asset markets to the rest of the world – rather than the other way round – making an analysis of the state of the S&P 500 a very good starting point for analysing any equity market.

The essential question then arises. Is it possible to undertake value-adding or loss-avoiding equity market timing decisions with any degree of analytical conviction? Such market timing decisions are unavoidable for any fund manager or investment strategist with responsibilities for funds that are not all-equity funds. Any fund required by its investors to hold a balance in their portfolios of cash, fixed interest investments of various kinds as well as the many alternative asset classes that might feature in portfolios, would have to exercise judgements about the risk inherent in equity markets at any point in time.

The risk that the equity markets might, as they have in the past, melt down or even melt up – only then perhaps to melt down again – must therefore be uppermost in the minds of all fund managers having to decide on an appropriate allocation of assets. Even those running all equity funds have to decide how to time turning newly entrusted cash into equities and, more important still, which particular equities to buy and sell.

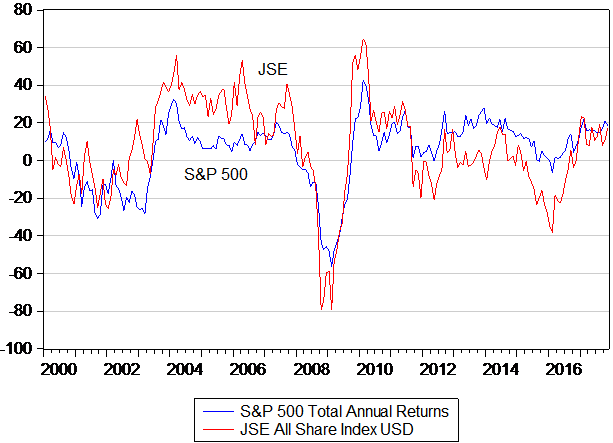

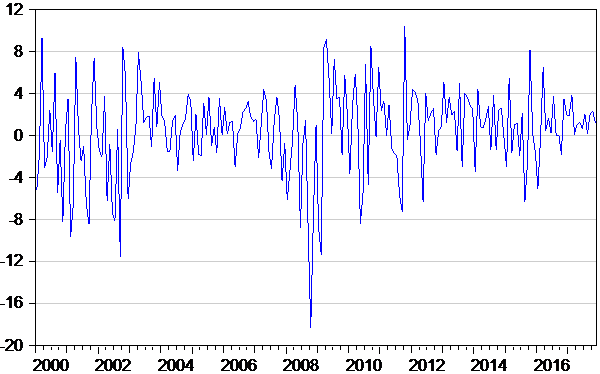

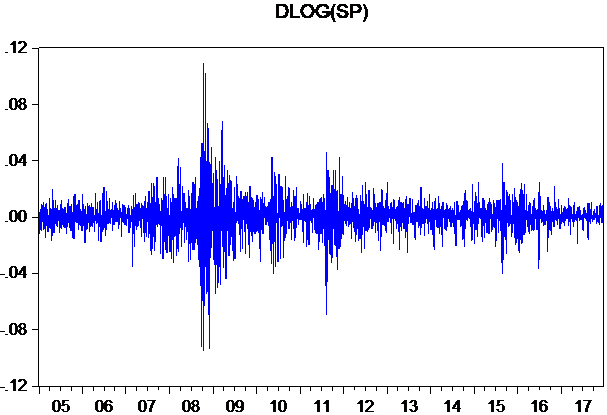

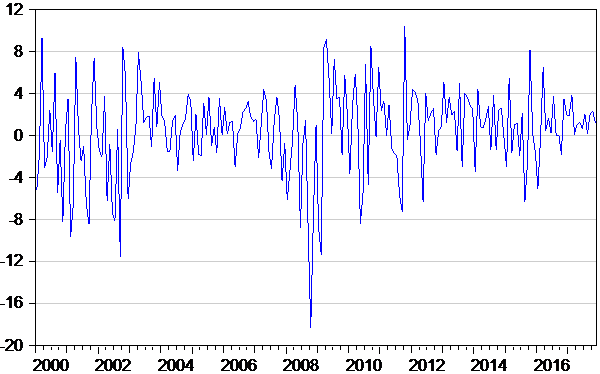

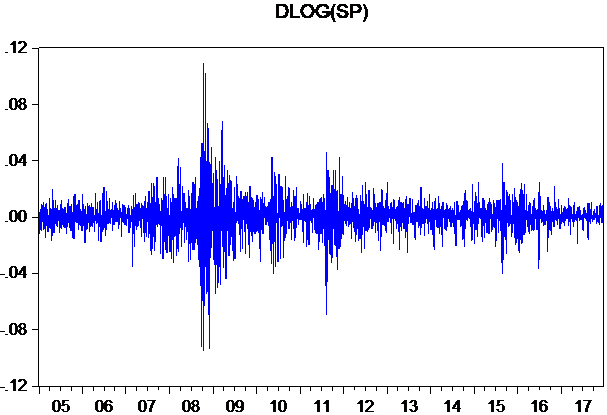

The broad direction of the equity or any other market can only be known after the event. From day to day, month to month or quarter to quarter, market prices and values are about as likely to go up as they are to go down. These short-term price moves therefore appear to observers as largely random, as the figure of monthly changes and daily moves in the S&P 500 Index shown below demonstrate. Note the still random (down/up, up/ down in no predictable order or magnitude) but very wide daily moves in the S&P 500 during 2008-2009 and during the euro bond crisis of 2011.

Figure 3: S&P 500 monthly returns (percent)

Source: Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment

Figure 4: S&P 500 daily returns (2005-2017)

Source: Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment

But these daily or monthly movements may reveal a broad drift in either direction, more up than down, or the other way round, measured over longer period of time. So when daily and monthly moves are converted into annual changes, observers will get the drift (after the event) and a persistent statistically smoothed trend in returns, that peaks and troughs in some more regular way, will be registered, as shown in figures one and two above. These phases, from top to bottom in annual returns, are defined as either a bull or bear market or something in between, depending on the depth or height of the following trough or peak, but can only be identified with hindsight.

Understanding how assets are valued

This does not mean that nothing meaningful can ever be said about the state of a market after it has moved higher or lower. With observation of the past we can understand the forces that have driven the value of any company higher or lower and so the average of them represented by a stock market index and therefore recognise the forces that might drive them higher or lower in the future, if past performance can be relied upon.

Successful, more profitable companies – those that earn a high return on the capital shareholders provide their managers – after all command higher values than less successful ones. And part of their success or failure will also have to do with the environment in which they operate. The laws and regulations, including the taxes their shareholders are subject to, will influence their ability to generate revenues and reduce costs, as will fiscal and monetary policies. The more certainty about these forces in the future, the less (more) risk to be discounted in the prices paid and the more (less) valuable will be the future flows of revenues and costs in which owners will share.

These market wide forces that determine the value of a share market index are in principle not difficult to identify. In practice they raise many unresolved issues about how best to give effect to the underlying theory. The economic caravan always moves on making it impossible to prove the superiority of one valuation approach over another. Holding other things equal is only possible in the laboratory, not in the economy.

The market can be thought of as conducting a continuous net present value (NPV) calculation, estimating a flow of benefits from share ownership over time, the numerator of the equation. That can be calculated as earnings (profits) or dividends or net (free after-capital expenditure) cash flow expected. The calculations of these are highly correlated when measured for an aggregate of all the firms that make up the Index. This expected performance of the market is then assumed to be discounted by a rate that reflects the required risk-adjusted rate of return set by the market.

The cost of owning shares rather than other assets, is given effect in the applied discount rate. It represents the opportunity foregone to own other assets, for example government or private bonds or cash, that offer pre-determined interest rate rewards with less default risk. In addition shareholders will, it is assumed, expect some additional reward, described as an equity risk premium (ERP) for the extra risks incurred in share ownership that offer no predetermined income. Hence a higher discount rate when the ERP is added to benchmark, default risk free fixed interest rates as provided by securities issued by a government. Such risks can be measured by the variability of the value of the share index from day to day, as shown above, a process of price determination that makes share prices more variable and less predictable than those of almost all other relevant asset classes.

These share prices will go up or down as the discount rate rises or falls with changes in interest rates. And with circumstances that cause investors to attach more uncertainty to the flow of benefits they expect from share ownership. The price of the shares goes lower or higher to compensate for these extra or reduced risks to the outlook for the economy and the companies who contribute to it.

The numerator of the NPV equation that summarises the expected flow of benefits to owners may be regarded (for reasons of simplicity) as (relatively) stable. A lower (higher) share price reconciles this given outlook with the required risk adjusted return that makes owning a share seem worthwhile. So when discount rates go up (down) – valuations (share prices) move in the opposite direction to improve (reduce) the expected returns from share ownership. Lower prices, other things being equal including expectations of profits to come, mean higher expected returns and vice versa.

Understanding and taking issue with the market consensus

One of the essential questions with which to interrogate the market, is to judge whether current market-determined interest rates are likely to move higher or lower or the environment that companies will operate in is going to become more or less helpful to their profitability. By definition, what surprises the market moves in interest rates or tax rates or risk premiums, will move valuations in the opposite direction. You may believe that the marketplace has misread the true state of affairs, such as the outlook for interest rates and risk premiums, and so has mispriced the share market, overvaluing or undervaluing it enough to encourage additional selling or buying.

The market consensus (revealed by the current level of the Index) will also have incorporated its expectations of performance to come by the companies represented in the Index. This consensus may also prove fallible. Earnings may be about to accelerate or decelerate in surprising ways. Operating profit margins may stay higher or lower for longer than expected. The economy itself may be about to enter an extended period of well-above past growth rates. If so, and you will have your own reasons for believing so, this would provide good reason to reduce or increase exposure.

Such contrarian opinions, if acted upon will add to or reduce exposure to equities. The market consensus is determined by its participants, all with the same incentive to understand it better, as you have, and is studied by many with great analytical skills and vast experience. Consensus has every reason to be the consensus. And when the consensus changes – as we have shown it so often changes – it will do so for good and well-informed reasons. Beating the market – that is getting market timing right – is a formidable task, so humility is advised.

While perfectly timing market entry or exit is not a task given to ordinary mortals, we can draw some helpful inferences about the condition of the market place, given this sense of what has driven past performance. We are in a position to judge how appropriately valued a market is at a point in time and therefore what would be required of the wider economic forces at work to take the market higher- or prevent it from going lower. We will attempt to recognise what is being assumed of the equity market – what assumptions are reflected in the prices paid for shares – and whether or not you can agree or differ from what is at all times the market consensus.

Our valuation exercises

We judge whether the equity market is demandingly or un-demandingly valued in the following way. We determine how current valuations are more or less demanding of additional dividends. Why dividends? Because they have the same meaning today as always: cash paid out to shareholders rather than retained by the enterprise. They are not subject to changing accounting conventions, such as the nature of capital expenditure and research and development expenditure that may or may not be fully expensed to reduce earnings. What may appear as an overvalued market would need a strong flow of dividends to justify current values and expectations. An undervalued market would be pricing in a slow-down in dividend payments. Good or poor dividend flows can take the market higher or lower.

Furthermore, we judge whether the market is more or less complacent about the discount rates that will be attached to these dividends to come. In this we are also aware that the interest rates we observe and that the market expects, as revealed by the level of long term interest rates and the slope of the yield curve, may be abnormally low or high – but might normalise to some degree in the near future.

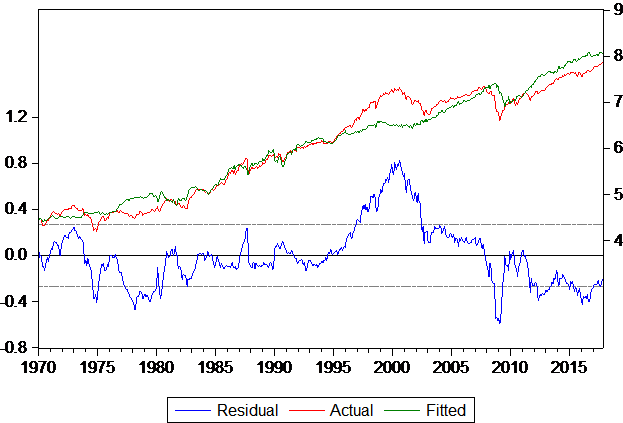

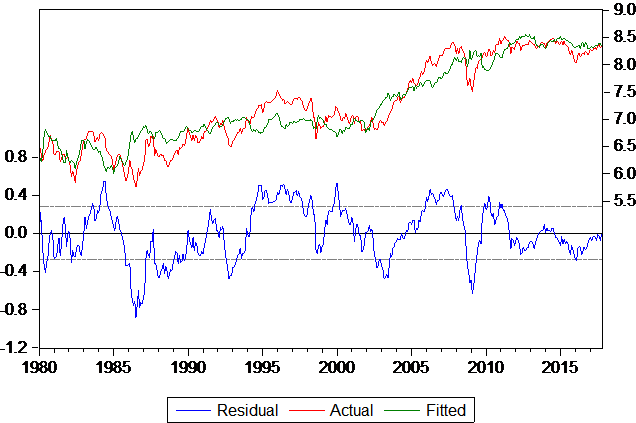

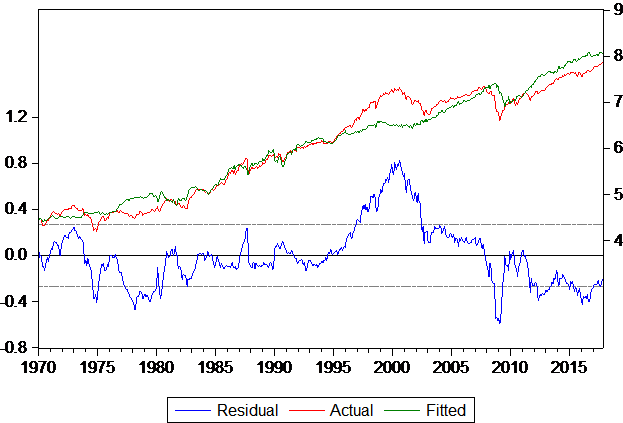

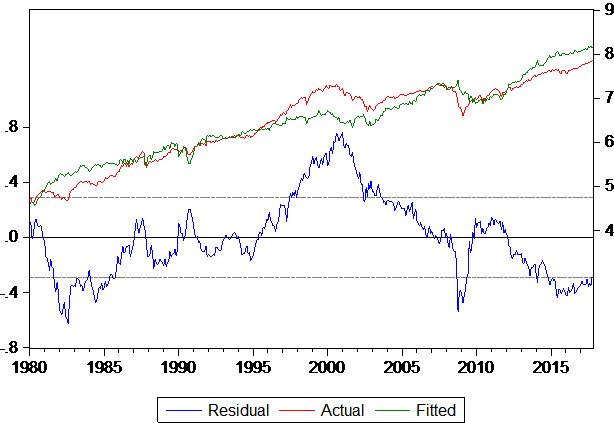

We utilise regression equations that compare the current level of the leading equity index the S&P 500 to the level predicted by trailing dividends and long-term interest rates. The results of such an exercise are shown below. The model equation predicts a significantly higher S&P 500 than is the case today, some 40% higher. By this standard the S&P is currently undervalued.

The model provides a very good fit and both explanatory variables easily pass the test for statistical significance and accord well with economic theory. It explains past market behaviour well.

Figure 5: Regression model* of the S&P 500 (1970-2017)

Source: Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment

*Representation:

LOG(SP) = -1.80463655704 + 1.18059721064*LOG(SPDIV) – 0.0727779346562*USGB10

We can back test the model. If the model was run with data only up to November 2014 when the S&P began its new upward momentum we would have received a very helpful signal that the S&P was in fact very undervalued at that time. This signal would have encouraged investors at that point in time to have maintained high equity weight in portfolios- or what is described as a risk-on position.

Similarly had we applied the model in early 2000, just before the so called Dot.com bubble burst, the model would have registered that the S&P 500 Index was then greatly overvalued for prevailing dividend flows and interest rates Reducing exposure to equities at that point in time would have been very much the right approach to have taken – as we soon came to find out. We should add however that the model would also have registered a high degree of overvaluation as many as three years before the market fell away from its high peak. Even irrational exuberance, as Alan Greenspan memorably described it in 1997, perhaps relying on a similar approach to value determination, or its reverse undue pessimism, can persist for an extended period of time, making our model or any such valuation exercise based on historical performance unhelpful as a short-term trading model, but still valuable as a basis with which to interrogate market consensus.

In our models we regard the value of the S&P 500 as representing the present value of a flow of dividends (the performance measure) discounted by its opportunity cost, represented by the interest rate (the expected return) on offer from a 10-year US bond yield. An alternative approach would be to compare the value of the Index to the expected economic performance of the companies included in the Index, and then to infer the discount rate that could equalise price and expected performance in the NPV equation.

The Holt system[1] undertakes this calculation. It estimates the free cash flow return on capital realised by and expected from all listed companies (CFROI) real cash flow return on real cash invested using the same algorithms applied to all the companies covered by the system and its data base. This analysis can be used to derive a market discount rate for any Index that equalises the value of an Index, for example the S&P 500, to the cash flows expected from it.

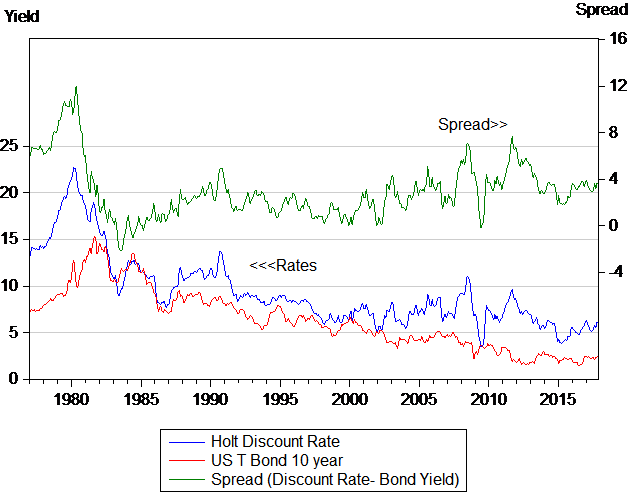

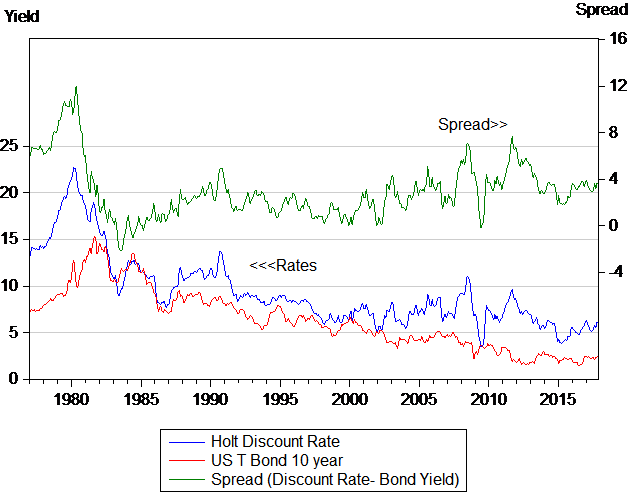

In the figure below we compare this nominal Holt discount rate for the S&P 500 to US long term interest rates. These discount rates have receded with long-term interest rates, as theory would predict. Note also that both interest and the Holt discount rate are at very low levels, implying higher share prices for any given flow of dividends.

Of greater importance perhaps for share prices than discount and interest rates is the spread between them. This spread, the extra risk premium for holding equities rather than bonds, has widened in recent years. While the discount rate may have declined, it has maintained and even increased the distance between it and interest rates, so encouraging demand for equities.

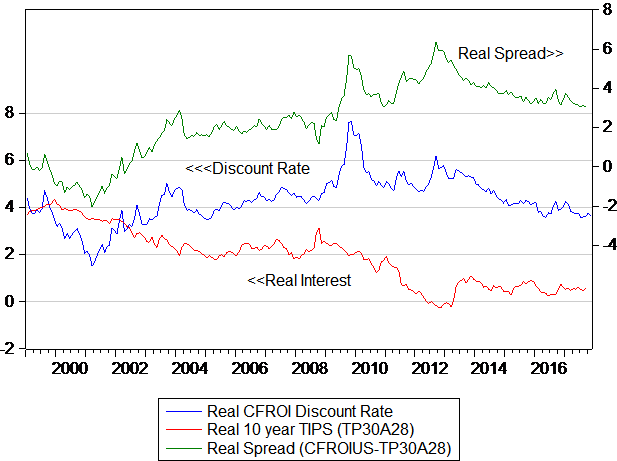

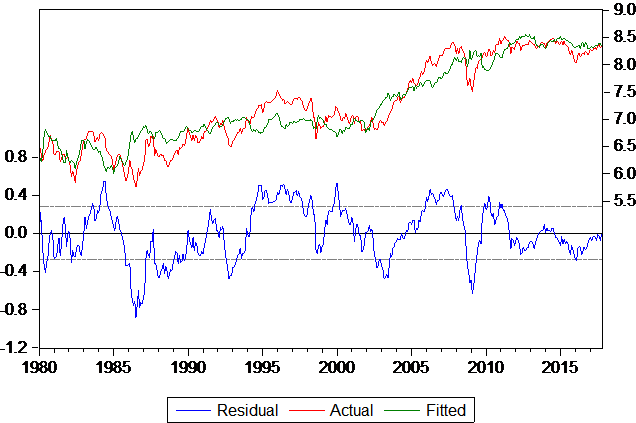

When we replace interest rates with this risk premium in our dividend discount model we get a very similar signal of a currently undervalued S&P 500 (see below).[2]

Figure 6: US Holt discount rates (nominal) US long bond yields (10 year) and risk spread

Source: Credit Suisse Holt, Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment

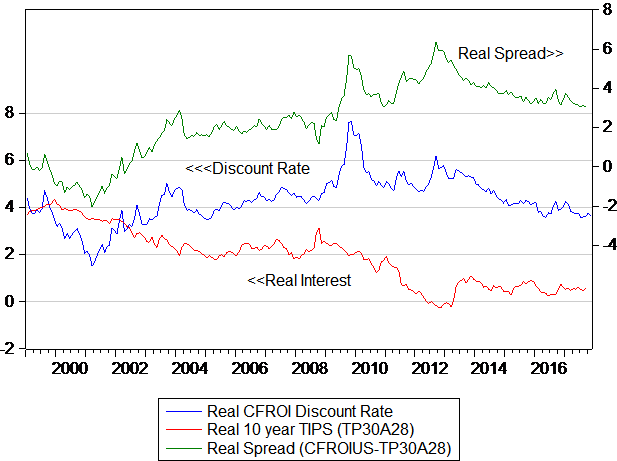

Figure 7: Real Holt discount rates and real interest rates and real risk spread

Source: Credit Suisse Holt, Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment

Figure 8: A model of the S&P 500 (explanatory variables, dividends and spread between discount rate and long term interest rates)*

*Representation of the equation:

LOG(SP) = -4.59846533561 + 1.51940769795*LOG(SPDIV) – 0.0501430590849*(CFROINOM-USGB10)

Source: Credit Suisse Holt, Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment

Therefore we conclude that the S&P 500, despite its recent strong upward momentum, is undervalued for current dividends and interest rates or the risk spread. However some caution about the level of the S&P Index is called for by a sense that long-term interest rates are now very low and may well normalise. A further reason to be cautious about the current level of the S&P 500 is that the day-to-day volatility of the Index has been very low by comparison with the past. This indicates an unusual degree of comfort with the current state of the US share market. Were volatility to normalise, share prices would probably under pressure.

Hence our asset allocation advice has been to retain a neutral exposure to equities for now, with the next 18 months in mind. On a shorter term view (less than six months) however, we are of the view that upside strength is at least as likely as any move lower.

When we review the JSE applying a similar method of analysis, the rand values of the All Share Index appears as fairly valued for trailing dividends and US Interest rates. It also appears fairly valued when all the variables of the model are converted into US dollars. However when the (high) level of the S&P is included as an explanation of the USD value of the JSE in place of US interest rates the JSE appears as now attractively undervalued.

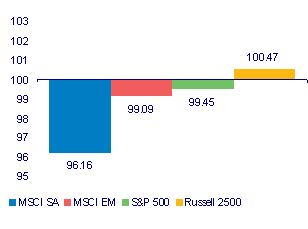

The S&P 500 is normally a rising tide that lifts all boats. But in the case of the JSE this has not been the recent case. Not only the JSE but emerging market equity indexes generally also lagged behind the S&P 500 after 2014 and until mid-2016. It will take less SA risk, which comes with an improved political dispensation, to focus global attention on the potential value in SA equities, particularly the companies heavily exposed to the SA economy. The SA political news has improved and the case for SA equities exposed to a potentially stronger SA economy, has also improved, making the case for a somewhat overweight exposure to this sector of the JSE.

Figure 9: A model of the US dollar value of the JSE with dividends and US interest rates*

*Representation:

LOG(JSE USD ) = 1.3925529347 + 0.776827626347*LOG(DIVIDENDS USD ) – 0.127168505553*US 10 Y Bond Yields

Source: Credit Suisse Holt, Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment

[1] Credit-suisse.com/holtmethodolgy

“HOLT derives a market-implied discount rate by equating firm enterprise value to the net present value of free cash flow (FCFF). HOLTs FCFF is generated by a systematic process based on consensus earnings estimates, a growth forecast, and Fade. This process is similar to calculating a yield-to-maturity on a bond” See Holt Notes November 2012

[2] In order to undertake the analysis over an extended period of time we added US inflation to the real Holt discount rate for the US sample to establish a nominal discount rate to be compared with nominal interest rate. An equivalent series of US real interest rates (Tips) is only available from 1997