Higher commodity prices could bring about higher global inflation. That would not necessarily be bad news for South Africa.

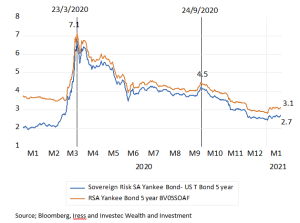

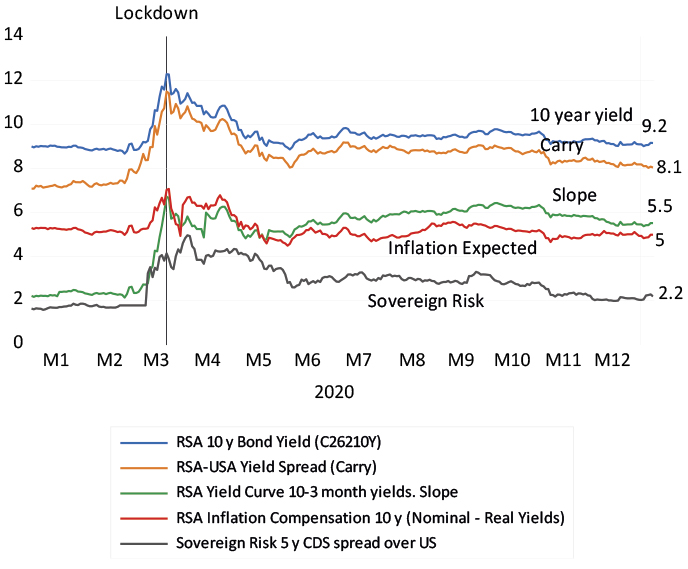

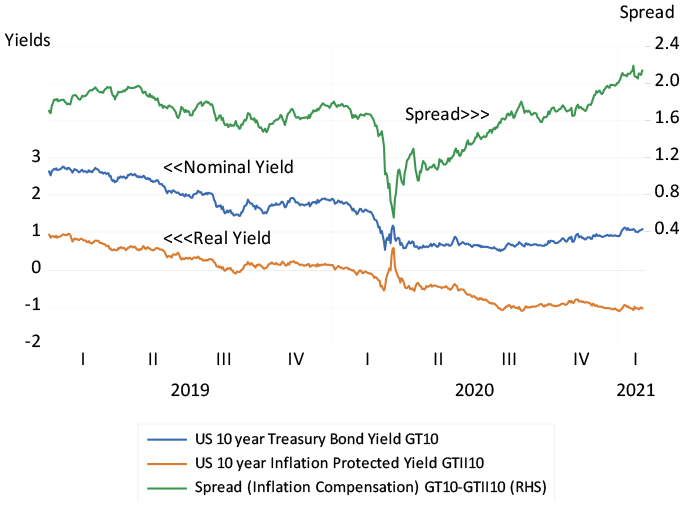

There is a hint of inflation in the frigid northern air. It’s being reflected in the long-end of the bond markets, the part of the yield curve that is vulnerable to signals of high inflation and the higher interest rates and lower bond values that follow. The compensation offered for bearing the risk that inflation may surprise on the upside is reflected in the spread between nominal and inflation-linked bond yields. These spreads have been widening in the US, and in low inflation countries like Germany and Japan.

This spread for 10-year bonds in the US was as little as 0.80% at the height of the Covid-19 crisis, was 1.63% at the end of September, and at the time of writing is at 2.14%. It has averaged 1.97% since 2010. The spread has widened because investors have forced the real yield lower, to -1.03%, further than they have pushed the nominal yield higher now, to 1.15%. This is still well below the post 2010 daily average of 2.25% (see figure below).

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment, 11 February 2021

Investors are paying up to insure themselves against higher inflation by buying inflation linkers and forcing real yields ever more negative. Clearly, the nominal yields continue to be repressed by Fed Bond buying (currently at a $120 billion monthly rate). One might think it’s easier to fight the Fed with inflation linkers, than via higher long bond yields, to which the currently low mortgage rates and a buoyant housing market are linked.

The Fed is insistent that it is not even thinking yet of tapering its bond purchases. The Treasury, now led by Janet Yellen, previously in charge of the Fed, insists that a new stimulus package of US$1.9 trillion is still needed for a US recovery.

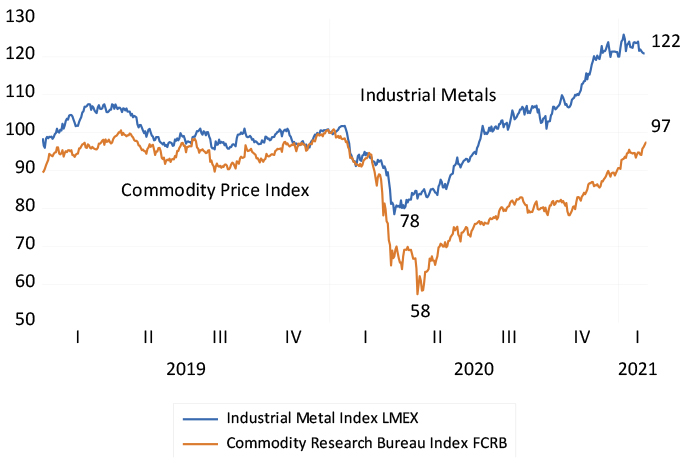

Metal and commodity prices, grains and oil are all rising sharply off depressed levels. Industrial metals are 45% up on the lows of last year, while a broader commodity price index that includes oil is up 51% off its lows of 2020.

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment, 11 February 2021

These higher input prices will not automatically lead to higher prices at the factory gate or at the supermarket. Manufacturers and retailers might prefer to pass on higher input costs. But they know better than to ignore the state of demand for their goods and services. They can only charge what their markets will bear, which will depend on demand that in turn will reflect policy settings.

Higher inflation rates cannot be sustained without consistent support from the demand side of the economy. Yet supply side-driven price shocks that depress spending on other goods and services can become inflationary, if accommodated by consistently easier monetary and fiscal policy. In the 1970s, it was not the oil price shocks that were inflationary. They were a severe tax on consumers and producers in the oil importing economies, which in turn depressed demand for all other goods and services. It was the easy monetary policy designed to counter these depressing effects that led to continuous increases in most prices. That was until Fed chief Paul Volker decided otherwise and was able to shut down demand with high interest rates and a contraction in money supply growth that reversed the inflation trends for some 40 years.

The financial markets will be alert to the prospects that demand for goods and services will prove excessive and inflationary in the years to come – and that they may not be dialed back quickly enough to hold back inflation.

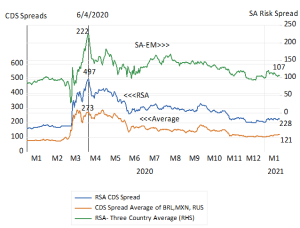

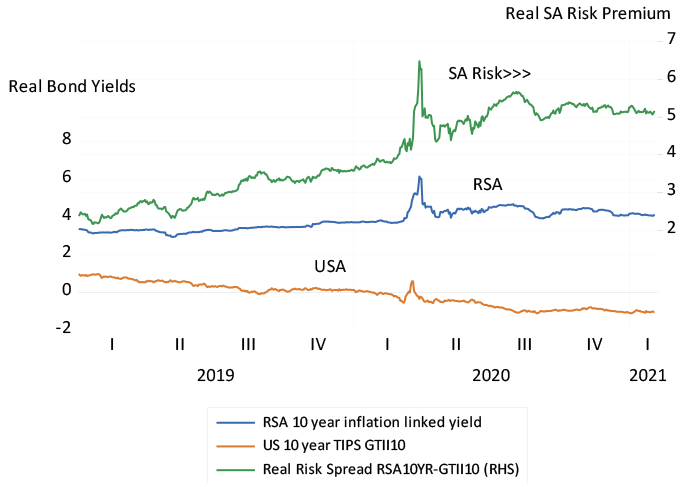

There is consolation for South Africa should global inflation accelerate. It will be accompanied by higher metal prices and perhaps bring a stronger rand to dampen our own inflation. It may also help reduce the large South Africa risk premium that so weakens the incentive to undertake capital expenditure as well as the value of South African business. Our inflation-linked 10-year bonds now yield a real 4.13%, a near record 5.15 percentage points more than US inflation linkers of the same duration. Any reduction in South African risk would thus be welcome.

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment, 11 February 2021