The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Reserve Bank last week found reasons to deny any relief to the hard pressed SA economy in the form of lower short term interest rates. And to do so despite the very good prospect of less inflation and still slower growth to come.

According to the MPC statement:

“The MPC assesses the risks to the inflation outlook to be more or less balanced. Domestic demand pressures remain subdued, and, given the continued negative consumer and business sentiment, the risks to the growth outlook are assessed to be on the downside.”

Concern about the possible direction of the rand appears as the principle reason for the MPC to delay any action on interest rates and wait for further evidence of lower inflation.

To quote the MPC further:

“The rand remains a key upside risk to the forecast. The rand has, however, been surprisingly resilient in the face of recent domestic developments. This is partly due to offsetting factors, particularly positive sentiment towards emerging markets and the improved current account balance.”

But as the MPC must surely know, the future of foreign exchange value of the rand – weaker or stronger – will always be uncertain because it is at risk of political and global forces well beyond the influence of Reserve Bank actions or interest rate settings. Over the past year the rand has strengthened for global reasons, common to all emerging market currencies and, as acknowledged by the MPC, despite the Zuma-induced uncertainties about the future course of fiscal policy.

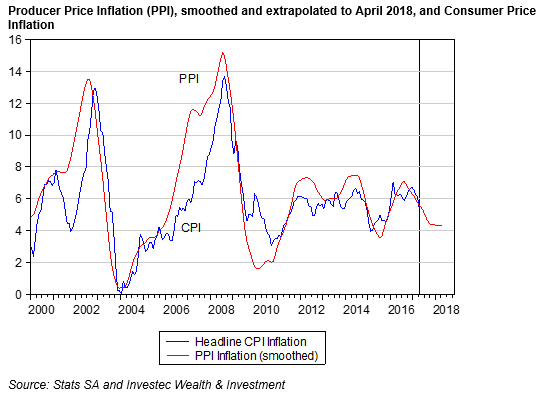

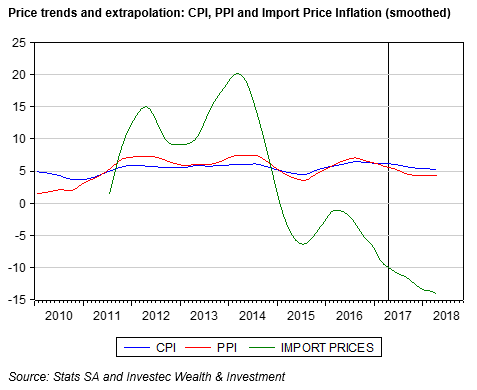

What is known about changes in the exchange value of the rand is that it will make exports and imports more or less expensive and usually lead the inflation rate higher or lower. In the figures below we show how the Import Price Index leads the Producer Price Index that in turn leads the Consumer Price Index in a consistent way. Given the recent strength in the rand, the trend is strongly pointing to lower inflation to come. Indeed, the MPC was surprised by the latest lower headline inflation rate reported for inflation, a lower rate that has still to be incorporated into its own forecasts of inflation.

The so-called pass through effect of the exchange rate on domestic prices, will also depend on also uncertain, global prices that also effect the US dollar prices of imported goods and services- particularly the dollar price of a barrel of oil. Other uncertainties will also influence domestic prices as the MPC acknowledges (for example electricity prices) as will expenditure taxes and excise duties – again forces not influenced by the interest rates. The unpredictable harvest is another major uncertainty that influences prices in SA – for now this is helping materially to reduce the inflation rate.

Exchange rate moves and other shocks, unconnected to the level of spending in the economy, are regarded as supply-side shocks that register in the CPI temporarily. Unless the shocks are continuously repeated in the same direction, they fall out of the CPI after 12 months. Hence monetary theory tells us these are temporary forces acting on prices that should best be ignored by monetary policy.

Interest rates will however influence spending in the economy in a predictable way and are called for when there are excess levels of demand. This is usually accompanied by increases in the money and credit supplies. This is far from the current case in South Africa, where spending and credit growth remains subdued and hence calls for lower interest rates, perhaps much lower.

This all raises the rationality of interest rate settings in SA that react to forces that are impossible to predict with any confidence – for example the exchange rate, over which monetary policy has no influence. Supply side shocks on inflation in SA have (wrongly in my opinion) allowed to influence interest rate settings with all inflationary forces treated as the same threat by monetary policy, regardless of its provenance. This has been the case since early 2014 in response to rand weakness and a drought that both forced prices higher. But a positive supply side shock on prices of the kind South Africa is now benefitting from (a stronger rand as well as a much improved harvest) is surely to be acted upon with urgency. Waiting to see what will happen to the exchange rate is simply to prolong the agony of tolerating slow growth for no good anti-inflation reason.

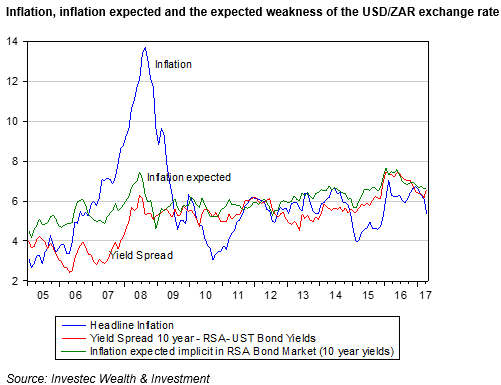

And in response to the inevitable Reserve Bank retort that failure to act on inflation will lead to more inflation expected and hence more inflation to come, I would suggest that this theory, on which the Reserve Bank relies so heavily to justify higher interest rates, has little support from the evidence of the inflationary process in SA. Inflation expectations have remained persistently high, as has the expected weakness of the rand, even as inflation itself has moved higher or lower. Evidence furthermore suggests that inflation expected, if anything, follows rather than leads realised inflation.

More important, it is highly unlikely that inflation expected can decline with the persistent market view that the rand will weaken by 6% p.a. or more each year for the next 10 years, as has been the persistent trend. Inflation expectations have proved very hard to subdue, despite the determination of the Reserve Bank to act against inflation, without obvious benefits for the inflation rate and regardless of the negative impact higher interest rates have on the subdued growth in demand.

Inflation expectations are measured below by the difference between nominal bond yields and their inflation-linked equivalents of similar tenure. The expected path of the USD/ZAR is measured by the difference between RSA bond yields and their US Treasury equivalents. These are compared to actual inflation in the graph below. As may be seen, inflation has been far more variable than inflation expected or the expected weakness of the rand. For the record, since 2005, measured at month end, the headline inflation rate has averaged 5.9% p.a, with a standard deviation (SD) of 2.2% p.a. Inflation expected has been much more stable, while it also averaged 5.9% p.a with a reduced SD of 0.71% p.a, while the spread between 10 year RSA yields and US Treasuries – a very good proxy for the extra cost of buying dollars for forward delivery – averaged 5.25 p.a. at month end with a SD of 1.2% p.a.

It will probably take an extended period of low inflation to reduce these expectations of inflation and rand weakness. Sacrificing economic growth for an inflation rate that has proved largely beyond the control of the Reserve Bank has never seemed to me to be good monetary policy. And it makes even less sense now that the inflation outlook has improved, even if this should prove temporary. 31 May 2017