Should we be frightened of our banks and their shadows or should we rather learn how to deal with banking failure?

Shadow banks rather than non-bank financial intermediaries

A new description – shadow banks – has entered the financial lexicon. The term is, as we may infer, is not used in a positive context. Rather it is to alert the public to the potential dangers in shadow banks, as opposed to the presumably better regulated banks proper.

This is a use of language consistent with one of the dictionary definitions of the word:

A dominant or pervasive threat, influence, or atmosphere, especially one causing gloom, fear, doubt, or the like: They lived under the shadow of war.

Or perhaps alluding to shadowy, defined as:

| 1. | full of shadows; dark; shady |

| 2. | resembling a shadow in faintness; vague |

| 3. | illusory or imaginary |

| 4. | mysterious or secretive: a shadowy underworld figure

Source: www.Dictionary.com |

An older, less pejorative description of this class of financial institution or lender would have been non-bank financial intermediary or perhaps near-bank financial intermediary to describe those firms that closely resembled banks in their lending activities. Examples are mortgage lenders (once called building societies), insurance companies, pension funds, money market funds and unit trusts, all of which would have fall under the modern description, shadow banks.

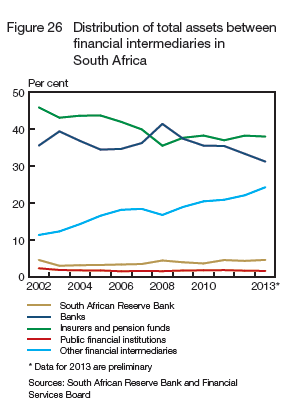

As we show below, drawing on the March 2014 Financial Stability Report of the SA Reserve Bank, the share of SA banks in the total business of Financial Intermediation in SA has declined over the past few years while the share of other financial intermediaries (including money market funds and unit trusts) has risen consistently, also in part at the expense of pension and retirement funds

Source; SA Reserve Bank Financial Stability Report, March 2014

The role of financial intermediaries is to facilitate the capital providing and raising activities of economic actors, domestic and foreign. They stand between (intermediate) the providers of capital in the economic system, be they households or firms, and those raising funds, to cover (temporary) financial deficits, that is, other households and firms and government agencies needing finance. They also compete for financial custom with those providers and users of finance who might bypass the financial intermediaries completely and deal directly with each other.

Such activities may be described as disintermediation when, for example, a firm previously dependent on bank finance bypasses the banks and issues its own debt or equity in the financial markets. The subscribers to such issues may however well be other financial intermediaries, for example pension funds, in which case it is the banks that will have been disintermediated.

Why banks are different from all other financial intermediaries

What then makes banks different in principle from other financial intermediaries? It may be in the detailed manner in which they are regulated, as we indicate above. But pension and retirement funds are also subject to particular regulations and regulators designed to protect providers of capital to them as are the managers of money market funds or unit trusts.

Banks are different not because they borrow and lend (or, more generally, raise and provide capital); they are different fundamentally because an important part of their function is to provide, via some of the deposit liabilities they raise, an alternative to the cash provided by the central bank that can be used for transactions, in the older terminology, as a much more convenient medium of exchange . In so doing, they provide an essential service to the economy, providing a payment system without which the modern economy would founder.

The danger with banks, narrowly confined to those few institutions that provide the payments mechanism, is that a large bank failure would bring down the payments mechanism with it. This is a danger to the broader economy almost too ghastly to contemplate. It is a danger that makes a large transaction clearing bank, on which all other financial institutions depend, not only to hold their cash, but more importantly, to help make payments, too big to fail. If such a bank were in danger of failing and unable to recapitalise itself in the market place, it would be obliged to call on the taxpayer for additional capital and the central bank for cash as a lender of last resort. A call that the central bank and the government could not, in good sense, resist. Shareholders given such a rescue should then lose all they have invested in the bank while depositors might be saved while bank creditors generally may or may not be obliged to accept a haircut. A possible haircut would help bank creditors exercise essential disciplines over banks as borrowers. The moral hazard of too big to fail and therefore too big to have to worry about default could be overcome without jeopardising the payments system with a predictable well recognised set of bankruptcy procedures for banks.

Clearly, facilitating payments by transferring deposits on demand of their depositors, is not all that banks do. Not all their funding is by way of deposits that may be transferred or withdrawn on demand. Term deposits as well as ordinary debt may be more important on their balance sheets than current accounts or transaction balances.

Banks, narrowly defined as the providers of a payments system, largely originated by offering an alternative medium of exchange to that of transferring gold or silver and the notes issued by a central banks to settle obligations. The owners of banks came to realise that they did not have to maintain anything like a 100% backing in gold or notes or deposits with the central banks for the deposits that could be withdrawn without notice, to survive profitably.

Fractional reserve banking was seen to be possible and profitable. In other words, the interest spread between the cost of raising deposits, with demand deposits paying the lowest interest or no interest at all, helped the banks make profits on the spread between their borrowing costs and interest income and so helped pay for the costs of maintaining the payments mechanism – a form of cross subsidy. It may be surmised that had the banks had to levy fees to cover all the costs, including a return on capital, of providing the payments mechanism, bank deposits might have proved less attractive and the growth of retail banks accordingly more inhibited than it was.

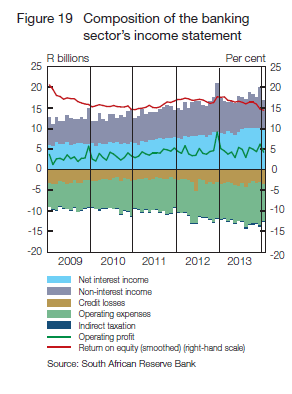

Banks in SA have become more dependent on net interest income in recent years, rising from about 5% to 10% of net income, while operating expenses have grown by about the same percentage. Return on equity has declined but remains a respectable 15% p.a.

Source; SA Reserve Bank Financial Stability Report, March 2014

The inevitable risks in fractional reserve banking and leveraged banks

Such fractional reserves however do pose a risk to the shareholders of banks as well as to their depositors. There might be a run on the bank that could cause the bank to fail, making the shares they owned in the bank valueless. Clearly, the interest earning assets it typically held could not be cashed in as easily as its deposit liabilities. Banking failures led to responses by regulators – firstly in the form of a compulsory cash to deposit ratio demanded of banks and in the form of deposit insurance designed to protect the smaller depositor. This was introduced in the US in the 1930s in response to the Great Depression and the banking failures associated with it.

Compared to most other financial institutions, including the so-called shadow banks, banks proper have always been among the most highly leveraged of business enterprises.. Their debts include all deposits, current and time deposits, equivalent to 90% or more of their assets, leaving little room for errors in the loans made.

The protection provided to depositors in the form of required cash or liquid asset reserves could not insure any bank or financial institution against the bad loans that could wipe out shareholders equity and cause a bank to go out of business. Hence the regulatory focus in recent years, not so much on cash adequacy, but on equity capital adequacy. The Basel rules promoted by the central bankers’ central bank, the Bank for International Settlements located in Basel, Switzerland, have imposed higher equity capital ratios of banks.

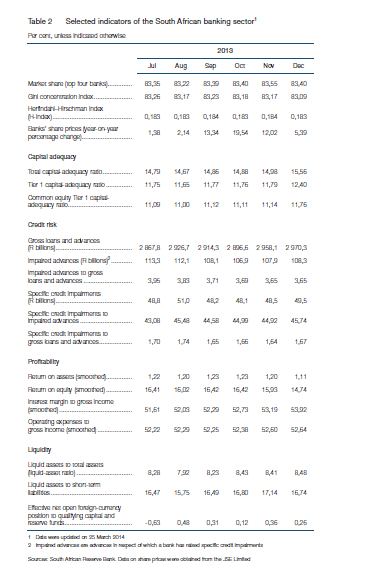

Understandably, the SA Reserve Bank as the regulator of the SA banks has given attention in its Financial Stability Report to the capital adequacy as well as the operating character of the banks under their supervision. The results of this analysis indicate that by international standards, the four large SA banks are well capitalised and well managed. As the table below shows, a capital to asset ratio of nearly 15% provides a return on banking shareholders’ equity of close to 15%, even though the return on total assets held by the banks is only 1.1%. Without high degrees of leverage SA banks might not be profitable enough to be willing to cross-subsidise the payments mechanism. If so other providers of a payments mechanism would then have to be found.

Funding such alternative providers with fees charged might not seem an attractive alternative to the current banking system that facilitates payments, partly through the interest spread, but with the danger than banks can fail. Dealing with the possibility of failure may well prove a better approach than imposing capital and cash requirements of banks that make them unable to easily stay in business.

There are no guarantees against banking failure

There is no guarantee that regulated bank capital, adequate for normal times and not so demanding as to threaten the profitability of banks and their survival as business enterprises, would be sufficient to support the banks in abnormal times. The global financial crisis of 2008 took place in most unusual circumstances, that is when the an average house price in the US declined by as much as 30% from peak to trough. Such declines meant that much of the mortgage lending of US banks had to be written off. Even a capital adequacy ratio of 15% might not protect a banking system, with a typically large dependence on mortgage lending, against failure, should the security in house prices collapse as they did in the US. SA banks have held up to 50% of all their assets in the form of nominally secure mortgage loans. They too would not have survived a collapse in house prices of similar magnitude.

Is it possible to insulate the payments mechanism from other banking activity? And what would it cost the holders of transaction balances?

It may be possible, given modern technology, to separate the payments system from bank lending and borrowing. The payments system could be conceivably managed by the specialised equivalents of a credit card company that would compete for non interest bearing transactions balances on a fee only basis. The transfer mechanism could well be a smart phone or some equivalent device.

The proviso would have to be 100% reserve backing for these balances held for clients to transfer. These reserves that would fully cover the liability would have to take the form of a cash deposit with the central bank or notes held in the ATMs. A deposit with a private bank would not be sufficient to the purpose- the other private bank, unlike a central bank can also fail and so bring down the payments system. If such a separation of banking from payments was enforced by regulation, large banks might not then be too big to fail any more than any other financial intermediary or indeed any other business enterprise might be regarded as too big to fail. But the unsubsidised transaction fees that would have to be levied to cover the costs of such an independent payments system, fully protected against failure, that would include an appropriate return on shareholders capital invested in such payment companies, might prove more onerous than the costs of maintaining transaction balances with the banks today that provide a bundle of services, including facilitating transactions.

It is striking how expensive it is to transfer cash through the specialised agencies that provide a pure money transfer service. A fee of 5% or more of the value of such a transaction is not unusual. The case for bundling banking services, even should banks need to be recapitalised should they fail in unusual circumstances, may well be a price worth paying. In other words what is required for financial stability and a low cost payments service is a predictable rescue service for the few large banks that manage the payments system.