Category: Current Research

The elusive notion of risk

Risk is an elusive concept to pin down and for investors to grapple with in practical,

measurable terms.

Investors who take a position on the stock market understand clearly what it means when they’re told their investment has produced a particular return over a particular period.

Most will also tell you they understand the notion of investment risk as an uncertainty of outcome; in particular, the higher the risk one is exposed to, the higher the chance that one loses one’s money. However, it is also accepted that in order to obtain good returns, one needs to take on extra risk. Then, in hindsight, risk is often used to explain why the realised return on an investment is high, on the one hand, or sometimes disastrously low on the other.

Underlying these perceptions of risk is the fundamental market tenet that one must expect to get rewarded for taking a position on an uncertain future. Therefore, markets must “price” risk into a share price, so that the higher the perceived risk of that investment, the higher the required future return on the investment. The problem is that neither this market-determined required return nor the associated risk is objectively measurable.

Still, plenty of people have tried. Quantitative financial analysts and the pioneering work of Nobel prize-winning economist Harry Markowitz use a statistical measure known as standard deviation (of return) as a proxy for risk. Typically, researchers in financial analysis will calculate an estimate of this standard deviation by using past values of share price returns.

In other words, to calculate the risk of a quoted company they would first compute the daily (or weekly) return of the share price over a certain period, and then compute the standard deviation of those returns. This measure, often termed volatility, is then taken as a measure of company risk. We will discuss below the flaws in this approach to measuring risk, but first consider some examples of situations where risk is much more precisely measurable.

In the game of roulette, played in casinos and assuming, of course, an unbiased wheel, we have constant probabilities of the ball landing on any of 36 numbers and zero at each spin of the wheel. It will be easily accepted that the risk involved in a bet on, say, red is much less than the risk of betting on the number 8-black, and one is rewarded accordingly.

If a red number comes up and you’ve bet R1 on red, you get R2 back. If you bet R1 on black and it comes up, you get R36 back.

Because the probabilities are fixed at each spin of the wheel, you could precisely

calculate the expected return of your bet and the associated standard deviation of that return, which proxies for risk.

When one plays a game with fixed probabilities, one always knows precisely what one’s expected return is. But in financial markets, event probabilities are not known precisely and change over time.

The key point is that when one plays a game with fixed and known probabilities, and

places a particular bet in that game, one always knows precisely what one’s expected

return is, and also the risk one is exposed to.

But in financial markets, event probabilities are not known precisely and, in fact, change continuously over time. What’s more, there is no possible repetition within an economic system as there is in roulette; the clock cannot be put back, and no process can ever be repeated in exactly the same way.

However, in the case of measuring risk and return in financial markets, we can make some headway in certain circumstances.

For example, assuming the SA government does not default on its contractual payment obligation, one can calculate the exact realised return on an RSA government bond held to maturity.

This required return must reflect the chance of a country default (if there is a default, the return is zero). Apart from its local rand borrowing, the SA government also borrows money on foreign markets denominated in dollars. These SA “Yankee bonds” are traded in New York, along with similar dollar-denominated bonds from other countries.

The required premium of the return (the spread) over and above the return an investor obtains on US government bonds of similar tenure is termed the sovereign risk. It is a measure of the probability of the bonds being paid out, according to contract, in dollars.

One can then calculate the spreads for the different countries which have issued dollar bonds. So, in this case, one can quite precisely compare the market’s perceived risk of default for different countries in paying these dollar-denominated bonds, and compare sovereign risk across different countries.

In the share market, there is no similarly definitive way to obtain the expected return or the risk of any company share on the basis of share market prices. Market analysts often use proxies for comparative value (and hence comparative risk) such as p:es and various measures of yield, such as dividend yield or earnings yield. The underlying principle is that a high-risk company should be reflected in a comparatively low market price, given the current earnings or the dividend payout.

Quantitative portfolio analysts are, however, given the even more challenging task of

combining different shares and instruments into a portfolio of assets expected to yield some overall return for some, often pre-mandated, risk.

They are thus faced with the problem of estimating portfolio (or share) risk in order to construct portfolios that fall within their given risk mandate. Given this problem, analysts almost always opt for using the estimated standard deviation of historical share price returns as a measure of volatility, which are then used as a proxy for risk.

There are plenty of problems associated with using past market data to measure risk or return But there are plenty of problems associated with using past market data to measure risk or return; the underlying issue is that markets are assumed to be efficient. This means the share price at any time can be assumed to reflect known information about the underlying company, but that price will continuously change as new information flows into the market.

Given that this new information is, by definition, unexpected and hence not predictable in any way, the resulting movement in share prices is, in turn, unpredictable. Therefore, past returns can give no indication of what future returns might be.

Risk, in contrast, may have some momentum in that a dramatic event, such as 9/11, will generally give rise to an extended period of return volatility, as markets grapple to understand and price in the impact of the event on share values.

However, though we may be able to anticipate volatility in the short term, the ability to do so over time is confounded by the statistical requirement of parameter stationarity.

In other words, if one wants to estimate a parameter using observations of that parameter over time, the parameter one is measuring cannot itself change over that period.

It’s a bit like locating a target when it’s moving, but your locating method must assume that the target is stationary. In the case of share price (or portfolio) volatility, this is an untenable assumption.

The conclusion is that any attempt to measure risk is problematic, especially in the

context of listed companies.

However, there is little acknowledgment of this fact by analysts. Analysts require

estimates of risk as a key input into almost any comparative share valuation or portfolio recommendation, but carefully avoid any interrogation of the validity of their estimates of risk. Individual investors may believe they understand risk, but their perceptions are often governed by whatever return they receive.

So: risk is an elusive concept to pin down and for investors to grapple with in practical, measurable terms. Fortunately, investors can usually take comfort in the one clear truth offered up by financial analysis. This is that the only sensible investment strategy is to carefully diversify one’s portfolio across as many asset classes as possible.

Then, assuming the world continues to advance technologically in the same innovative and productive ways it has in the past, irrespective of what unexpected challenges may arise, one’s investment will yield attractive returns over a long period.

Barr is emeritus professor of statistical sciences at the University of Cape Town (UCT);

Kantor chairs the Investec Wealth & Investment Research Institute and is emeritus

professor of economics at UCT

Book chapter: The theory and practice of investment strategy

In this chapter I reflect on the role of the economist/strategist in the business of managing wealth. It is a role I have played since my first involvement with the financial markets in the early nineteen-nineties.

I share the ideas about financial markets and their relationship to the economy that have informed my work as an investment strategist and economist in the financial markets. I say a little about my personal involvement in the financial markets.

I explain the importance of a well-considered investment strategy, for not only the wealth owner or their agents, the portfolio managers, but for the greater good.

These thoughts are followed by a case study of how I go about my work reading the financial markets that I hope will be of interest and helpful to those with a close interest in financial markets. The analysis offered is an example of pattern recognition that analysts and indeed all businesses rely upon to improve their predictions. This recognition has become so much easier over my years with the ready availability of low-cost computing power, most helpful software, and abundant data, easily downloaded. Exhausting the data, testing a theory, looking for evidence to support a theory, becomes a matter of minutes rather than the years it took when I first took an interest in financial markets. Theory and observation run together, observations lead to theory and theory is tested by observation. My attempts to understand and explain the links between the financial markets and the economy and the economy and financial markets remains a work in progress that I hope to continue for as long as it makes sense for me to do so and worthwhile for those who engage with me.

Read the full chapter here: Chapter 10 – The theory and practice of investment strategy

Inflation of prices and wages – have they had any predictable consistent influence on output and employment in the US since 1970?

21st January 2019

Benign expectations of inflation and interest rates despite low rates of unemployment

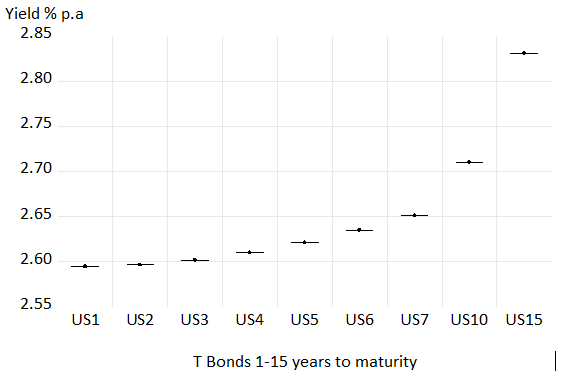

The US capital market in January 2019 reveals a very benign view of inflation and of the direction of interest rates. The long- term bond market indicates that inflation is expected to stay below an average 2% per annum over the next ten years. The difference between the yield on a vanilla 10 year Treasury on January 9th (2.71% p.a) and an 10 year Inflation protected US bond that day (0.833% p.a) is an explicit measure of inflation expected in the bond market. This yield spread gives long term investors in US Treasuries a mere 1.88% p.a extra yield for taking on the risk that inflation will reduce the real value of their interest income. And the Fed is confidently expected not to raise short term rates this year. The money market believed in January 2019 that there was only a one in four chance of the Fed Funds rate rising by 25 b.p. this year. On January 9th 2019, the one year treasury bond yield of 2.59% p.a. was expected to be only marginally higher, 2.66% p.a in five years. [1]

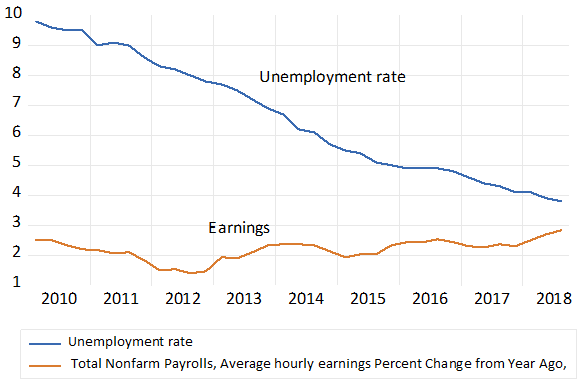

Are such views consistent with a very buoyant labour market it has been asked? Unemployment rates are at very low levels, below 4% of the labour force while average earnings are rising at about 3% p.a. These bouyant conditions in the labour market may portend more inflation and higher interest rates to confound the market consensus.

Fig. 1: The US Treasury Bond Yield Curve on January 9th 2019.

Source; Reuters-Thompson and Investec Wealth and Investment

Figure 2; Unemployment and earnings growth in the US

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

The relationship between wages and prices in the US

Do changes in prices lead or follow changes in wage rates in the US? The economic reality is that they both follow and lead. Both the price of labour – average wages and other benefits per hour of work and its cost to employers- and the price of a basket of goods and services, represented by the CPI, are determined more or less simultaneously and inter-dependently in their market places. As we show below the index of average wages and the CPI are highly correlated. How they interact is not nearly as obvious and may not be consistent enough to make for any convincing evidence of cause and effect- that is from prices to wages or wages leading prices.

The relationship between wages and prices and employment and GDP

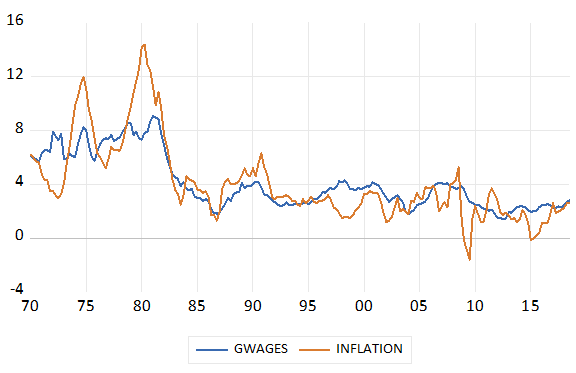

Fig.3 Wage and headline inflation in the U.S 1970-2018.3; Quarterly data, year on year percentage changes

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

As may be seen in the chart above wage inflation in the US ( year on year per cent changes in hourly earnings) appears to track headline inflation very closely and vice versa. Wage inflation has been less variable than headline inflation ( year on year change in the CPI) Headline inflation since 1970 has averaged 4.09% with a standard deviation (SD) of 2.95% p.a. while average wage inflation per annum has been a very similar 4.09% p.a, with a lower SD of 2.02% p.a.

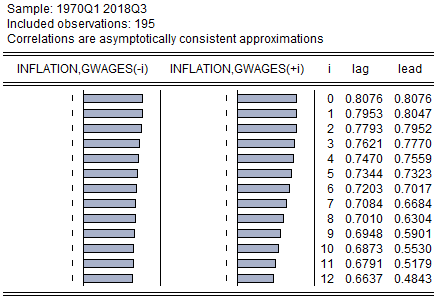

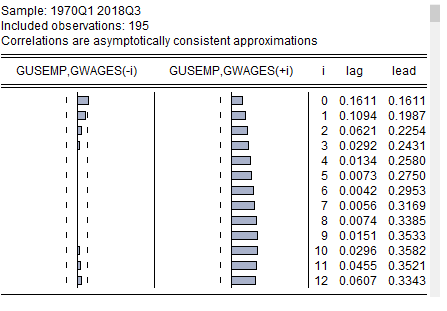

We show below a table of correlations of headline and wage inflation at different leads and lags. As may be seen the highest correlations are realized for contemporaneous growth rates. The correlations remain very similar for lags up to 12 quarters and point to no obviously important and reliable leads and lags that could inform any wage plus theory of inflation.

Table 1; Cross-Correlogram of inflation and growth in wages in the US. Quarterly data Y/Y percentage growth (1970.1-2018.3)

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

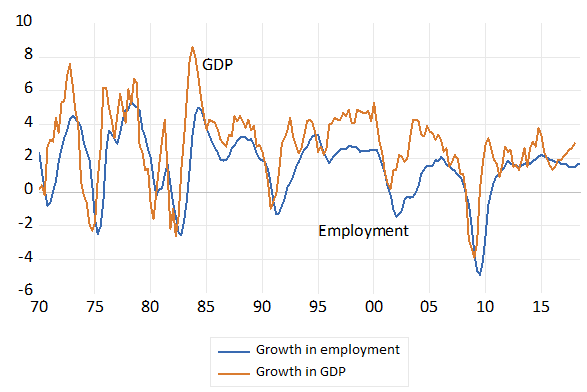

Fig.4 Growth in employment and GDP Quarterly data y/y percentage growth (1970.1-2018.3)

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

We show the very close relationship between the growth of payrolls and the growth in the U.S economy in the chart above. GDP has grown on average by 2.77% p.a since 1970 while employment has increased by 1.56% p.a on average since then. The correlation of the two growth series is 0.60 while, as may be seen, employment growth (SD 1.87% p.a) has been less variable than output growth (SD 2.18% p.a) GDP growth very consistently leads employment growth. The lag effect seems strongest at two quarters. The correlation between changes in GDP and changes in employment two quarters later is as high as 0.86.

We show the lag structure in the Cross-Correlogram below

Table 2. Cross-Correlogram of Growth in Employment and Wages in the US. Quarterly data y/y percentage growth (1970.1 2018.3)

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Why changes in wage rates and prices are so highly correlated

The markets for goods and the markets for labour have the general state of the economy in common. The wages and prices that emerge in the markets for labour and goods and services will be influenced by how rapidly the demand for and the supply of all goods, services and labour may be growing. Furthermore higher wages or prices will in turn restrain demands for labour and other goods and services effecting the observed wage rate and employment outcomes in the labour market.

Changes in prices, wages and interest rates have their causes (represented in the conventional supply and demand analysis by leftward or rightwards shifts in the demand and supply curves that cause prices to rise or fall) But any such shock to prices or wages or interest rates and asset prices will also have effects on demand or supply, as prices move higher or lower. Such effects can be represented by movements along the relevant demand or supply curves.

The essence of any helpful analysis of supply and demand forces at work is to recognize and identify the sequence of events that lead to any new equilibrium price when supply and demand are again in balance . That is to identify the initial causes of a price change, the supply side or demand side shock that gets prices or wages or interest rates moving in one or other direction, and their subsequent effects on prices and the further adjustments made by buyers and sellers to the shocks. An unexpected spurt of economic growth may well lead to more employment and higher real wages. That is cause a shift rightwards in the demand curve for labour. Higher real wages then serve to ration the available supply of labour under pressure from increased demands.

These higher wages may induce more potential workers to seek employment. Such responses would make the supply curve of labour more elastic in response to higher wages. Thus more worker employed will help offset the initial wage pressures emanating from the demand side of the market .

Supplies of goods and services and capital and labour may also come from abroad to add to supplies and so influence prices on the domestic markets. Trade and capital flows may alter the rate of exchange that, depending on their direction, may add to or reduce the price of imports in the local currency. And exports can add to demands – so competing with local buyers and to possibly price them out of the local market. It is demand and supply that determine prices and wages. The changing state of domestic demand may not be enough to push prices or wages consistently higher. The final outcomes for prices will also depend on the supply side responses.

Furthermore prices are not simply set as a pre-determined percentage higher than the cost of producing them. Of which the costs of employing workers may be a more or less important part, depending on the labour intensity of production. The state of the economy (demand) and the competition to supply customers will determine how much margin over costs will their way into the prices any firm will charge.

Costs to some firms are the prices charged by their suppliers- including their employees. The distinction between what may be described as costs, or alternatively prices, will be based on the position the buyer or seller occupies in the supply chain. In the very long run prices and the costs of supplying all goods or services offered will tend to converge. The relevant cost to be covered will include the opportunity costs of employing capital as well as labour.

Is it a matter of demand pull or cost push on prices- or is it both – with variable difficult to predict lags between prices and costs or costs and prices? The evidence of wage and price growth trends says it is both as would any full theory of wage and price determination.

Another force common to prices wages and interest rates is the increase in prices and wages expected in the future. The faster they are expected to increase the more workers and firms and investors for that matter will wish to charge upfront for their services. All this complexity makes any uni-directional wage or cost-plus theory of inflation of very limited explanatory or predictive power.

The Phillips curve – origins and uses.

There is an economic theory known as the Phillips curve, that predicts that decreases in the unemployment rate (increases in the demand for labour) would cause wages to rise faster and for prices and interest rates to follow. The original paper written in 1958[2] was primarily an exercise in innovative, early econometrics. It demonstrated how curves could be fitted to annual data on changes in wages and the unemployment rate. It showed a broadly negative relationship between wage rates and the unemployment rate. The theory was that increased demands for labour- represented by a lower unemployment rate -would lead to higher wages.

The data extended over a long run, 1861-1957. It was collected over a period when the United Kingdom was mostly on the gold standard and when inflation would have been confidently expected to be sustained at very low levels. Of interest is that Phillips in his paper was well-aware of the role variable import prices might play in influencing prices and wages. A force we would describe today as a supply side shock.

It was this theory that Keynesian economists invoked in the sixties to argue that more employment could be traded of for more inflation. The idea was that workers, unwilling to accept the wage cuts that might restore full employment, might be fooled by inflation that surreptitiously reduced their real wages and so encouraged employment. Employment opportunities that were presumed to be structurally deficient – depression economics that is.

The classical economists regarded the flexibility of wages and prices in the downward direction as the cure for recessions. The extended unemployment of the nineteen thirties appeared to indicate that any reliance on wage and price flexibility to restore full employment was unrealistic. Given that nominal wages were seen as rigid in the downward direction meant persistently high levels of unemployment. That is unless governments intervened to stimulate aggregate demand enough to cause inflation and thereby reduce real wages enough to encourage employment. The implications of the Phillips curve that appeared to trade higher nominal wages for more employment was generalised to imply a tradeoff of inflation for faster growth.

The predictive powers of the Phillips curve

The theory has had very poor powers of prediction- originally of what became high inflation and slower growth in the US and elsewhere in the nineteen seventies. Much higher average rates of inflation of prices and wages in the seventies were associated with much slower not faster growth. This lethal combination came to be described as stagflation. That inflation was accompanied by slower not faster growth encouraged monetarists with an alternative demand led rather than a wage led theory of inflation. The quantity theory of prices, reconfigured by Milton Friedman, regained its currency. [3]

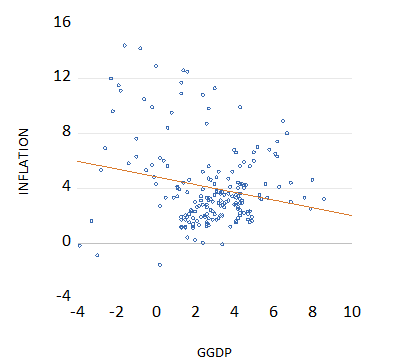

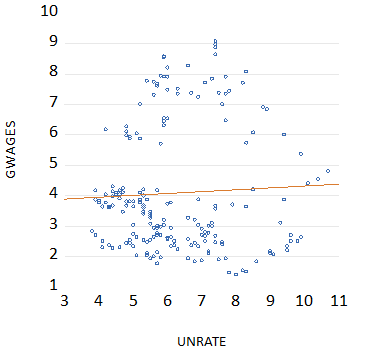

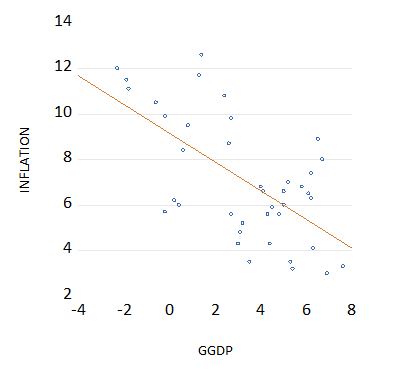

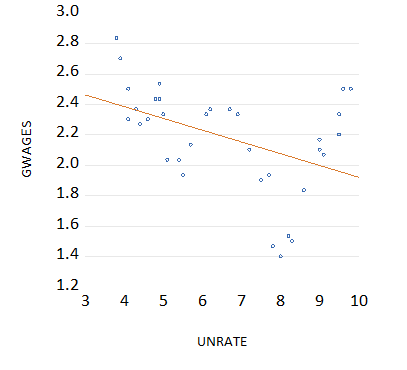

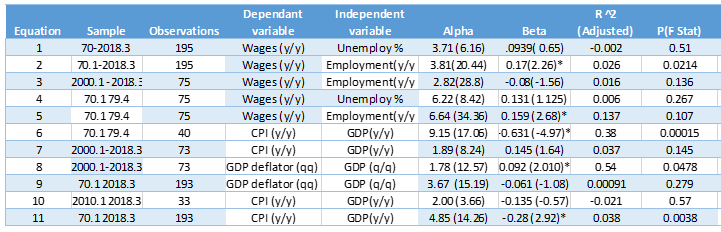

Any negative relationship between wages and unemployment (increased wage rates associated with less unemployment or more generally more inflation associated with faster GDP growth) in the US is conspicuously absent in the employment inflation wage growth and GDP data ever since the 1970’s and in-between. We demonstrate the absence of any support for the Phillips curve in the charts and tables below.

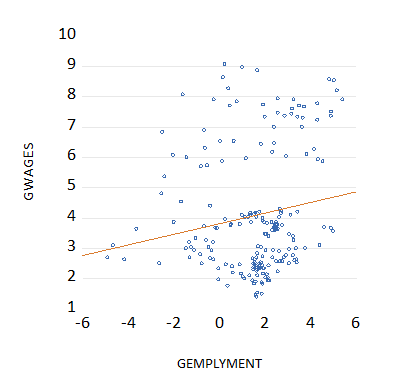

As may be seen the scatter plots and the regression lines that connect them indicate that unemployment and wage increases and inflation and GDP growth are not related in any statistically significant way. This is true of the relationship between unemployment (or employment) over the entire period 1970 – to 2018 and sub-periods including more recently between 2000 and 2018 and between 2010 and 2018. The correlations for the entire period and for sub-periods within them between wage growth and employment growth and between inflation and output growth are close to zero as may be seen in the table of regression results. The scatter plots and their regression lines shown below indicate the absence of any consistently meaningful relationships very clearly.

The table of regression results shown below confirms the absence of any predictable statistically significant relationship between employment and wage growth or between GDP growth and prices or indeed vice-versa. As may be seen the single equation regression equations are almost all explained by their alphas. The goodness of the fits of the regressions are very poor indeed. Their respective R squares that are all close to zero- indicating that the growth rates are generally not related at all. The betas that determine the slope of the regression lines are of small magnitude and most do not pass the test of statistical significance at the 95% confidence level – and some that do, for example equations 6 and 11, indicate that the relationship between wage growth and employment is a negative rather than a positive one. The presence of serial correlation in the equations as demonstrated by the Durbin-Watson (DW)statistic indicates that these betas may well be biased estimates. It would seem very clear that there is no trade-off between wage and price growth and the growth in output and employment in the US. Any forecast hoping to predict inflation via recent trends in wage rates or employment would be ill-advised to do so, given past performance.

Fig.5; Inflation and growth in real GDP Quarterly Data Growth year on year. Scatter Plot and Regression line (1970.1 2018.3)

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig 6: Growth in wages y/y and the unemployment rate 1970.1 2018.3 Scatter Plot and regression line

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig.7; Growth in wages and growth in employment (1970,1 2018.3) Scatter Plot and regression line

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig.8; Inflation and growth in GDP (1970-79) Scatter Plot and regression Line

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig 9; Growth in wages and unemployment rate (2010.1 2018.3) Scatter Plot and regression line

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Table 2; Regression results

[4] The data is downloaded from the St Louis Federal Reserve data base Fred. The data is quarterly and seasonally adjusted and all growth rates have been calculated by Fred and downloaded into Eviews. Eviews was used to run the regression equations and construct the charts. Wages were represented by average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees in the private sector. (AHETP) Employment by Total Nonfarm Payrolls (PAYEMS) The unemployment rate (UNRATE) is the civilian unemployment rate. The GDP and CPI have their conventional descriptions

Not inflation- only unexpected inflation has real effects on output and employment

That is because firms and workers build inflation into their wage and price settings. Much faster inflation in the seventies did not come to surprise workers and did not mean lower real wage costs for the firms that hired them. Moreover prices rise faster as they did in the seventies, as the oil price rose so dramatically, when Middle East producers exercised their newly found monopoly power to restrict supplies. Negative supply side shocks that raise prices and reduce demand will complicate the relationship between price and wage changes.

A larger positive supply side shock for the global economy that caused downward pressure on prices was the entrance of China and Chinese labour and enterprise into the global economy. It brought a very large increase in the supply of goods- especially of manufactured goods. This addition to supplies at highly competitive prices lowered the prices established producers outside of China have been able to charge and forced many of them out of business.

The challenges for the economic forecaster

It is possible to build more complex multi- equation models that incorporated lags between GDP growth and employment growth and between changes in prices and wages to hopefully forecast inflation and growth. That is consistently with economic theory combined supply and demand forces and their feed-back effects with due importance attached to inflationary expectations and how they are established. If the feed-back effects however accurately identified are themselves of variable force through different phases of the business cycle the estimates of the equations are unlikely to deliver statistically meaningful results.

The accuracy of such forecasts will depend not only on the internal logic of the equations estimated, but on the assumptions made about the forces outside the model. The predictive power of such models must be tested out of the sample periods over which the coefficients of the model were estimated. Forecasters inside and outside of central banks have every incentive to make accurate forecasts of inflation, growth, interest rates and asset prices. The ability of any of these models to consistently beat the market place has to date never been obvious. And were they so able the market itself would become less volatile.

Inflationary expectations and the reactions of central bankers[5]

The importance of inflationary expectations in the determination of the price and wage level has much impressed itself on central bankers. They recognized that there was no output or employment benefit to be gained from more inflation. That only unexpectedly higher inflation might stimulate more output- and unexpectedly low inflation will do the opposite. The central bankers have come to understand that their ability to surprise the market and their forecasts is very limited. Given that is the importance workers (trades unions)and firms with price or wage setting powers would attach to predicting inflation as accurately as possible. They do so in order to avoid the potential income-sacrificing consequences of underestimating or over estimating inflation. Underestimating the inflation to come would mean setting wages and prices below where market forces might have justified. Overestimating inflation might mean wages and prices having to reverse direction with a consequent loss of output and employment. Successfully second -guessing central bank action that helps determine the rate of inflation is an essential ingredient for successful market makers.

When the surprises are revealed they will come with losses of output and employment as the market adjusts or in the case of surprisingly rapid inflation exchange rate weakness and higher interest rates will follow. Dealing with such surprises adds volatility to prices and asset prices. A risky environment discourages savings, inward capital flows and investment and reduces potential output and its growth.

Thus central bank wisdom is that they should avoid as far as possible inflation shocks and associated monetary policy actions that might surprise the market place. Rather they have come to understand that their task is offer the market place a highly predictable and low rate of inflation in the interest of permanently faster growth rates. Hence inflation targeting.

A South African post-script

This is the objective of the SA Reserve Bank -enshrined in our constitution – as we have been well reminded recently. But success in achieving balanced growth does demand more flexibility than the SA Reserve Bank has demonstrated. The flexibility to recognize that powerful and frequent supply side shocks to inflation – exchange rate, oil price and food price shocks call for very different interest rate responses than when demand is leading inflation.

Alas demand led inflation has been conspicuously absent in recent years. Wage increases in SA therefore explain unemployment not inflation. Accurately forecasting inflation in SA – better than the Reserve Bank has been able to do – means anticipating the exchange rate and the oil price and rainfall in the maize triangle. A near impossible task it may be suggested. Eliminating demand led inflation ( policy settings that attempt to balance domestic demand and supply) rather than directly aiming at an inflation rate that is largely beyond its control is a much more realistic and appropriate task for the SA Reserve Bank. And the market place can fully understand these realities. Inflation forecast and so inflationary expectations in SA will be rational ones.

[1] By Reuters-Thompson interpolating the yield curve that is reproduced here

[2] A.W.Phillips, The relationship between unemployment and the rate of change of money wage rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957,Economica vol 25 (19580 pp 283-99

[3] My own interpretation of the analytical disputes of the time can be found in my Rational Expectations and Economic Thought, Journal of Economic Literature, Volume XV11 9December 1979),pp 1422-1441 it referred to the pioneering work on the role of expectations in macro-economics of Milton Friedman (1968) and Edmund S.Phelps (1967 and 1970)

[5] See my, The Beliefs of Central Bankers about Inflation and the Business Cycle—and Some Reasons to Question the Faith, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance; Volume 28, Number 1, Winter 2016

Recent Research

Much of my recent research output has been published in the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, now published for Columbia Business School by Wiley. (See references below) Some earlier versions of this work may be found on the Blog- but copyright prevents me from posting the published versions.

Global Trade – Hostage to the Volatile US Dollar, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 30, Number 1, Winter 2018

The Beliefs of Central Bankers about Inflation and the Business Cycle—and Some Reasons to Question the Faith, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance; Volume 28, Number 1, Winter 2016

A South African Success Story; Excellence in the Corporate use of capital and its Social Benefits with David Holland, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 26, Number 2, Spring 2014

2013 Nobel Prize Revisited: Do Shiller’s Models Really Have Predictive Power? with Christopher Holdsworth, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 26 Number 2 Spring 2014

Lessons from the Global Financial Crisis (Or Why Capital Structure Is Too Important to Be Left to Regulation) with Christopher Holdsworth, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 22, Number 3, Summer 2010

Time-series-based Financial Analysis led us down a blind alley – could Big Data Analysis repeat the same mistake?

Abstract

This paper considers the new thrust of Statistical Analysis and Operations Research in the area of so-called Big Data. It considers the general underlying principles of good statistical modelling, particularly from the perspective of Pidd (2009), and how some initiatives in the Big Data area may not have applied these principles correctly. In particular, it notes that demonstrations of applicable techniques, which are purported to be appropriate for Big Data, frequently use data sets of stock market share prices and derivatives because of the huge quantum of high frequency share price data which is available. The paper goes on to critique the frequent use of such historical stock market price data to forecast stock market prices using time series analysis and details the limitations of such practice, suggesting that a large volume of work done towards this end by statisticians and financial analysts should be treated with circumspection. It is seen as unfortunate that a large contingent of extremely able students are directed into areas that encourage time series modelling of stock market data with the promise of forecasting what is essentially unforecastable. The paper also considers which approaches may be appropriately applied to model and understand the process of share price determination, and discusses the contributions of the Nobel-prize winning economists Fama and Shiller.

The paper then concludes by suggesting that the Big Data initiative should be treated with some caution and further echoes the sentiments of Pidd; namely that the focus in Operations Research and Statistics should remain firmly on creative modelling, rather than on the singular pursuit of large amounts of data.

Read full paper here: Kantor 2018 – Big Data

Machines in a world of abundance

Will the intelligent machines ease us out of work as we understand it?

Where will all the workers go?

The pace of technological and scientific change is both rapid and accelerating. Robots with powerful computers have invaded the factory floor and the warehouses and distribution centres with great effectiveness. The number of workers employed in them have accordingly shrunk. Transistors, sensors and cameras will soon combine to eliminate the need for someone in the driver’s or pilot’s seat, and move us faster and more safely than now.

A common modern refrain in response to the challenge of the robots is where will all the workers go? Will it be into other jobs or into unemployment? And if the cohort of the unemployed is to become a much larger one for want of employment opportunity, how will society cope with the assumed failure of an economy to employ most of those who seek work?

Replacing workers with machines is not something new. Smashing the hand loom machines was not helpful

The advance of knowledge and its application to production – so improving the ratio of output to inputs of resources – of land, labour and capital is not something new. Economic progress, scientific advances accompanied, sometimes led, by the invention of ever more powerful machines, has been more or less continuous since the 17th century. The east, that once so lagged behind the west in economic and military prowess, is rapidly catching up in the economic and scientific stakes, applying much of the same proven recipe for economic progress.

The increased production of goods and services enhanced by ever more productive machinery of all kinds (medical equipment included) has been accompanied by consistent advances in the average standard of living and life expectancies and a rapid growth in population. The population of the world has more than doubled since 1970, increasing from 3 billion to more than 7 billion today. On average we are better supported today by higher levels of production of the essentials for life: food, shelter and medical care. And we are provided for with more of the luxuries of life, including more time off work.

We choose more leisure – not working – when we can afford to do so

A preference for more leisure has been exercised in greater volume as the average hours per week worked has declined. Leisure is a desired form of consumption for which income and other forms of consumption have been willingly sacrificed. Choices made by those who can afford to reduce hours at work, and some of the drudgery and dangers of work, have been eliminated with the aid of machines, helping to make work more pleasurable and less onerous. Nice work – if you can get it.

This growth in population has been accompanied by a rapid (more or less) increase in the numbers employed (that is in the work force). The greater number of humans surviving and employed today has also been accompanied by a large reduction (billions fewer) of those who survive despite absolute poverty. Absolute poverty is conventionally defined as those earning or consuming the equivalent of US$2 per day. Most would describe these developments as progress even if happiness – whatever this means – may be as elusive as ever.

These increases in incomes and output represent impressive and consistent economic progress (compounding growth in output and incomes) made over the past 300 years. Yet there is more to be done to raise average living standards to the levels now realised by those in the upper quintiles of the distribution of incomes in the most economically developed economies. Surely this is an economic state to be preferred and aspired to by all who lack this degree of material comfort and the choices it brings with it – including time spent not toiling? And if past performance is anything to go by, it is a realistic prospect. After all, incomes double every 20 years if they grow at 3% a year.

Only the (few) well off in their comfort zones would wish to halt economic progress

There is therefore every reason out of concern for our fellow humans to encourage the scientific revolution that will make humans and the machines who complement their efforts, ever more productive. The capabilities of the robots are bound to improve with developments in artificial intelligence (AI) that will make the machines less dependent on their human supervisors. The numbers of workers employed designing, building, servicing and operating each robotically enhanced unit of equipment, will also decline, also aided in their efforts by AI and digitilisation. The robots, with enough enhanced artificial intelligence at their disposal, may be able to write their own operating instructions. Therefore fewer writers of code for them will be called for.

Output per person employed will rise accordingly with the application and utilisation of these new wondrous machines. Economists describe this process as an increase in the ratio of capital to labour in the production process. It rose in the past when machines first replaced animal and human power and production became mechanised before being automated to an ever greater degree. Production – the output of goods and services produced with the aid of capital equipment – including what we now describe as robots of one kind or another, will grow as it has in the past, aided by ever more superior equipment. And perhaps the output of goods and services produced, with the aid of capital, will increase even more rapidly than before.

Will machines become substitutes for, rather than complements to, human action?

But will the pace of change now leave many more behind? Unable to find useful work and so effectively replaced by the machines, rather than able to earn more, because of the equipment they work with, the less skilled today may be more vulnerable than they have proved to be in the past, less able to compete directly with the robots, for robotic type work, which may be all many humans undertake and are capable of.

And the same displaced workers may be unable, for want of relevant skills, to find alternative employment, building and servicing the ever more numerous robots. Or capable of providing service to those earning higher incomes from owning, designing, managing, building and maintaining the robots.

All may not be about to be lost by human agents in the competition with machines. I am informed that while a modern computer can now always beat a chess grand master. The master chess player accompanied by a computer will beat the computer unaided. The highest incomes in the years to come may be earned by those best able to work with the robots.

Those who thrive with the help of robots are likely to choose more leisure and the services that accompany time off work. Empathetic humans may have great advantages, compared to inhuman robots, when supplying the services that accompany leisure including, walking the dogs and looking after the cats and birds of the affluent. Particularly should alternative employment and income earning opportunities in the production of goods (rather than services accompanying leisure) be lacking. Humans may try harder to serve and so help keep the robots at bay.

Humans, as we are well aware, are highly adaptable to changing circumstances. This is why we have become the pre-eminent species and there are so many more of us commanding the planet. We may have enough time to adapt to the competition from robots and the opportunities they open up, including becoming more skilled teachers, with the aid of robots. Computers may (at last) be productive in adding to the skills of their students as they have done for chess players. So improving their own skills, productivity and employment prospects as they improve the skills and employment prospects for their students.

The scope for redistributing what is produced more abundantly will increase

But empathetic humans can do more than compete more effectively. A growing volume of output made possible by science, technology and robots provides more opportunity to take from the more productive to give to the less productive, including the unemployed and those without capacity to contribute much to the output of the economy. The past tells us that as GDP increases, so does the size of government and the share of incomes (output or GDP) that is taxed and redistributed by governments exercising their power to do so. This is a process that is strongly encouraged by the less economically advantaged and to which their elected representatives will respond. The ability to respond to the collective will and impulse, will be governed by the growth in the economy. The more that is produced the more that can be redistributed.

The relatively poor and the unemployed too will thus continue to look to an improved standard of living if the society is productive enough and the tax base large enough to make more welfare spending feasible. We can expect more of this compulsory taking and giving should our economies become more productive and not all share equally in its advance, as is bound to be the case. This is if fast exponential growth continues over many years because the incentives to innovate and invent, the true drivers of economic progress, are encouraged enough by economic policy.

The interdependence of welfare and work – and of employment benefits and employment opportunities – and of income and its growth

Such generous welfare will have some of the consequences we can already observe. The better the state – that is other people – provide for the unemployed – those willing and able to work –the greater has to be the employment benefits that make choosing work – sacrificing leisure – a sensible decision. And the less skilled are less likely to command rewards from work that exceeds improved benefits available to them when not working. Their reservation wage – the employment benefits that make sense working for – may be too high for some to choose work. For them, without the skills that command higher more attractive rewards from employers, leisure is the rational alternative to work. They will choose more of it if employment prospects deteriorate.

Thus welfare benefits of all kinds will tend to reduce the supply of potential workers and, perhaps unintentionally, increase the employment benefits of those in work. Decent work is likely to become ever more decent as the economy grows and welfare becomes more generous to the relatively poor. But as these employment benefits improve and the cost of hiring rises, employers will be encouraged to further substitute machines (capital) for labour. In doing so they perhaps leave a greater proportion of the adult population not working or even seeking work. They choose leisure – because in a sense they can afford it.

A productive society may well be able to afford to support the relatively poor and the unemployed generously. But will it do so generously enough to avoid resentment of the better off? Resentment that given political consequences may well lead to policies that disrupt the economy and its progress. The process of economic growth depends on society accepting – at least to some degree – unequal rewards for unequal contributions. Is not acceptance of those forces of invention and innovation that will drive the development of robots and AI essential to the purpose of economic progress? Invention and innovation and risk taking generally are the true source of economic progress and need to be given the right encouragement. The economic problem of not enough to go around is only resolved by permitting a degree of unequal rewards for unequal effort and outcomes. Inhibiting the rewards for economic success may well prevent it occurring.

People not working on a larger scale because the society can afford to support their leisure – given a lack of skills and adaptability – may create a whole set of problems for the more or less permanently non-working. Society may be required to find ways to make not working psychologically meaningful and acceptable to the tax payers. Compulsory work, perhaps by helping less fortunate humans and work improving the environment, in exchange for welfare, may become a component of the adjustment to growing affluence made possible by the robots (robots it might be added who can help avoid the drudgery and danger of many kinds of work that workers do not regard as any more than a means to the end of consumption).

What if the robots delivered true economic abundance and solved the economic problem for us?

But what if we took the advance of the robots to its full logical conclusion? An imaginary state of the world when robots aided by superior AI completely replaced all humans in the work place1. The robots with enough AI may completely replace their human managers and collaborators. They may be able to manage themselves with a single minded purpose (programmed originally by humans) to produce more goods and services for humans to consume, and for whom the robots are the servants (perhaps better described as slaves) with no preferences of their own.

If robots replaced all workers the only income earned would be earned owning robots who produced all the goods and services supplied to an economy, that is to the people who make up the society. And there would be an overwhelming abundance of goods and services for humans to consume. It should be recognised that if and when the robots take over, all the work the economic problem of scarcity will have been resolved. The difficulty of society having to determine what should be produced and who should benefit from the production would have been overcome by the advance of the robots. Trade-offs between who produces and who benefits from production will no longer be relevant. The perhaps unimaginably productive robots will be providing more than enough goods and services so that no person will be short of anything to accompany their leisure.

Since there would be no work for humans to engage in there would be no income from work to be sacrificed for leisure or to be saved to be consumed in the future. The only source of capital to replace and produce new and better robots would then be the savings made out of income received owning robots.

Abundance solves not only poverty but inequality of incomes as well

Given that there is no economic problem, the inequality problem (derived increasingly over time by owning robots in unequal amounts) would be solved by expropriating and nationalising the primary means of production – the super productive robots. The collective will take over from the individual without any of the usual dire consequences when the economic problem exists and demands resolution.

The now all embracing collective, the state as owner of all the abundant means of production – the robots – would spread the equivalent of the abundant free cash flow generated by the robot owning state-owned firms equally to all the population. That is the state as owner would spread equally all the surplus (cash) around that has been generated by the productive robots, after capital reinvested in new and better robots and in the social infrastructure that supports the leisure of all not working.

For example, the supply of roads and swimming pools and sports stadiums has to be determined and the balance distributed as income to the population. Intelligent robots will manage the state-owned companies and issue the tenders and welfare checks in response to the instructions of the politicians, elected by the people at leisure

It should be understood that in these circumstances of robot-supplied abundance, the robots would be programmed (by other robots) only to meet the full and satiable demands of the leisure class – that is the entire population. These robots will not require any of the incentives that are now necessary to get humans to work well by appealing to their self-interest.

Adam Smith’s hidden hand that turns private interest into public benefits will have done its work. The unequal rewards that we now have to offer to talented humans so that they will deliver the goods will have become redundant. Self-interest becomes irrelevant in the midst of abundance: everybody has more than enough of everything and have only to decide how to allocate their time. Hence owning anything will make no sense and protecting rights of ownership (property rights) will have served their function.

Robots will just do what other robots programmed by robots tell them to do and they will produce more than enough to keep us at comfortable leisure and out of work. They will be productive slaves without any preferences of their own to get in the way of maximising output. AI therefore will have replaced intelligent humans in the production of everything – produced abundantly by robots for all humans to consume in as much quantity as they might desire. There would be no differential rewards to breed resentment. Full equality of incomes is a logical consequence of super abundance.

A different world would mean the evolution of a different species

That some people have a (natural) human capacity for greater enjoyment of leisure than others may then become a problem that will have to be addressed by the political process. Legislation against unequal utility might be called for, with the required dose of pharmaceuticals (or implanting of genes) to make sure that all are rendered equal in consumption and happiness.

The economic logic of robot-supplied abundance that demands no sacrifices from humans in the form of work or saving, would be a very different world. It would be essentially inhuman as far as we understand the human condition. That is the harsh one we inhabit that demands sacrifice (work and savings) and the acceptance (very difficult for many particularly intellectuals and academics whose rewards are no well correlated with their IQs) of unequal rewards for unequal effort and sacrifice.

Abundance would require that humans evolve as a very different species. Humans would be back in the Garden of Eden, perhaps then as the first time having to start all over again learning about the necessity of work and sacrifice. Perhaps abundance is a frightening prospect to many. But even if it is, would it be wise to stop the advance of the robots that promises to eliminate poverty and so even work itself? Choosing abundance (or rejecting it) will be a collective one made by those in the way of the marching robots. 19 March 2018

1A possibility welcomed in inimitable style by the most famous economist of his time John Maynard Keynes in his essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren written in1930 and published in his Essays in Persuasion, Macmillan and Company, London, 1931. The book is available as a Project Gutenberg Canada Ebook. www.gutenberg.ca

Keynes writes “….I draw the conclusion that, assuming no important wars and no important increase in population, the economic problem may be solved, or be at least within sight of solution, within a hundred years. This means that the economic problem is not – if we look into the future – the permanent problem of the human race……..”

And later

“……Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced his real, his permanent problem- how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.

The strenuous purposeful money-makers may carry all of us along with them into the lap of of economic abundance. But it will be those peoples, who can keep alive, and cultivate into a fuller perfection, the art of life itself and do not sell themselves for the means of life, who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes.”

Point of View: Artificial intelligence and the productivity conundrum

The world’s first artificially intelligent lawyer has arrived. Called Ross, and built on IBM’s famous cognitive computer called Watson, it has been “employed” by US firm Baker & Hostetler to work in its bankruptcy practice.

According to Futurism.com, Ross can “read and understand language, postulate hypotheses when asked questions, research, and then generate responses (along with references and citations) to back up its conclusions. Ross also learns from experience, gaining speed and knowledge the more you interact with it”. (http://futurism.com/artificially-intelligent-lawyer-ross-hired-first-official-law-firm/)

It’s not just lawyers who should be looking over their shoulders. All sorts of knowledge workers could see their employment prospects and livelihoods threatened by artificial intelligence, including journalists, accountants, portfolio managers, even surgeons and physicians.

With the aid of the internet and easy access to case law and its interpretation, fewer lawyers may be required to resolve a bankruptcy procedure. Fewer analysts may be required to value a company with the aid of Bloomberg data and its accompanying suite of programmes. Lasers directed by unerringly accurate robots may well help reduce the time in the operating theatre and the dangers of doing so.

What is the impact of these newly adapted technologies on productivity in the industry and the economy as a whole? Let’s use the example of the artificially intelligent bankruptcy lawyer above. The productivity of the lawyers in bankruptcy practice can be defined as the number of cases concluded divided by the number of lawyer hours billed to do so*. Presumably the number of lawyers (and legal hours billed) will decline with the aid of Ross. Thus the surviving lawyers working on bankruptcy law in a legal practice will have become more productive in the sense of an increase in the ratio (cases concluded/hours billed). Measuring productivity in this case seems a simple task.

It becomes much more difficult to measure the productivity of a service provider when real output is much trickier, and sometimes impossible, to measure. One would not wish to measure the productivity of an analyst, journalist, artist or inventor of a new video game by the number of words written and published or number of pictures painted or pixels injected. The quality of the work produced is surely more important than the quantity of output and “quality” is recognised in revenues generated. As is admitted by the calculators of productivity, it is impossible to measure the productivity of government officials, because it is not possible to measure how much they produce. All that can be measured is their employment benefits – an input. In the case of an author, composer, copywriter or game developer, only the value of the royalties they have earned can be measured – their revenue line, not the time spent writing the masterpiece. Measuring productivity requires that inputs and outputs can be independently measured, which is not always the case, especially for service providers.

However, looking at the example of the number of bankruptcy cases (which we would regard as an independent measure of output), what if the quality of advice has improved even as the numbers of hours billed declines? The advice may be superior with the aid of Ross’s deep memory bank. How would we adjust for this quality dimension in our measure of legal productivity? The question is apposite for the service sector generally, where computers and data management (and improved knowledge) have presumably enhanced the quality of service provided by lawyers, analysts and other knowledge professions, including the improved offering of physicians supported by bigger data and better statistics. If the quality of advice has objectively improved, then any hour of consulting service will be delivering more in real terms than a case handled in the same time say 10 years before. The output of the consultant will in effect have increased, even if the input of time is the same. But by how much is the leading question. The physicians may be seeing the same number of patients a day, charging them higher fees, but they (their patients) are likely to be living longer and better lives.

In cases like this we will not be comparing like with like, apples with apples or aspirins with aspirins, making any measure of real output and so productivity over time a very difficult exercise and one subject to significant errors in what is measured. For example, your medical insurance may well have become more expensive – or your cover reduced – but are you not getting a better quality of medical service in return? And exactly how much better? In the case of medical insurance, only what you are paying – not your additional benefits – will find their way into the official price indices.

A further aspect is the impact of improved quality on the broader economy. If the bankruptcy cases are resolved with less billable time spent in court and hence with a larger percentage of debt being recovered with reduced legal expenses, this would be a clear gain to the creditors. Creditors would be better off in real terms, with less spent on legal fees and earlier resolution of their claims, meaning that the creditors could spend more on other goods or services or save more. And lawyers competing with each other for work that has become less costly for them to supply, may well charge you less for their time. It is competition for extra revenue that turns lower costs into lower prices – even in the legal profession – provided they do not collude on fees.

Could the GDP deflator, the price index that converts estimates of GDP in money of the day into a real equivalent, hope to pick this up with a high degree of accuracy? Enough to provide accurate measures of GDP or productivity growth over extended periods of time? The deflator used to convert nominal GDP into real GDP, attempts to adjust for quality improvements in the output of goods and, especially, services produced. Yet in South Africa, 68% of all value added is comprised of services of one kind or another the quality of which may well be changing over time, in ways that are very difficult to measure.

Ours is more of a service economy, than one that produces goods, the output of which is much more easily measured in units of more or less constant quality – for example number of bricks or tons of cement or steel. Thus, if we are underestimating quality improvements in the large service sector, we will be overestimating inflation and so underestimating the growth in real incomes, output and productivity.

Your real incomes and your productivity may well have increased even if you are taking home no more pay or other employment benefits. You may be benefitting from an enhanced quality of service as well as a very different mix of services than was available 10 years before, for example easy internet access that has so changed the way we work and play. This has become a particular problem in the developed world where prices as measured are generally falling. Deflation, rather than inflation, is the greater concern and nominal wages are not rising, even if productivity and the standard of living, differently measured and quality enhanced, is improving (though perhaps poorly recognised, as voters in their frustration at their constant money incomes turn to populists who promise a better standard of living). A mere one or two per cent extra a year factored into GDP or productivity growth measures, well within a range of possible measurement errors, would provide a very different impression of how the developed world is doing. A rising real standard of living, if only we could measure it, might well be accompanying stagnant employment benefits, when calculated in money of the day.

*One of the criteria the World Bank uses for measuring the ease of doing business in any country is outcomes in the bankruptcy courts. The tables below measure ease of doing business across a number of categories, and we show the SA and Australia findings where SA compares quite poorly. The ranking is, for example, 120/189 for ease of starting a business compared to 11 for Australia; and 41 for bankruptcy proceedings compared with 14 for Australia. Both countries rank poorly for trade across borders (130 and 89). Note we do much better than Australia when it comes to protecting minority investors: ranked 14 vs 66; and worse for getting credit, 59 Vs 5.

Point of View: A question of (investment) trusts

Understanding investment trusts and how they can add value for shareholders regardless of any apparent discount to NAV.

Remgro, through its various iterations, has proved to be one of the JSE’s great success stories. It has consistently provided its shareholders with market beating returns. Still family controlled, it has evolved from a tobacco company into a diversified conglomerate, an investment trust, controlling subsidiary companies in finance, industry and at times mining, some stock exchange listed, others unlisted. Restructuring and unbundling, including that of its interests in Richemont, have accompanied this path of impressive value creation for patient shareholders.

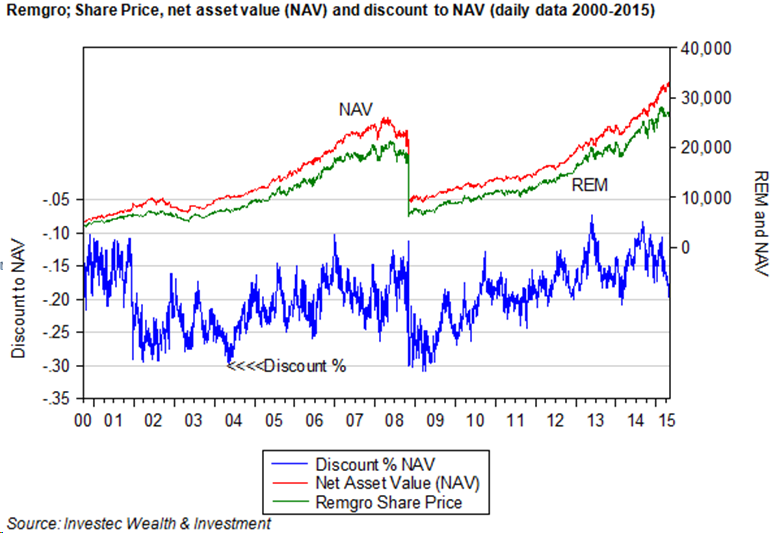

The most important recent unbundling exercise undertaken by Remgro was in 2008 when its shares in British American Tobacco (BTI), acquired earlier in exchange for its SA tobacco operations, were partly unbundled to its shareholders, accompanied by a secondary listing for BTI on the JSE. A further part of the Remgro shareholding in BTI was exchanged for shares in another JSE-listed counter and investment trust, Reinet, also under the same family control, with the intention to utilise its holding of BTI shares as currency for another diversified portfolio, with a focus on offshore opportunities. Since the BTI unbundling of 2008, Remgro has provided its shareholders with an average annual return (dividends plus capital appreciation, calculated each month) of 23%. This is well ahead of the returns provided by the JSE All Share Index, which averaged 17% p.a over the same period. Yet all the while these excellent and market beating returns were being generated, the Remgro shares are calculated to have traded at less than the value of its sum of parts, that is to say, it consistently traded at a discount to its net asset value (NAV).

The implication of this discount to NAV is that at any point in time the Remgro management could have added immediate value for its shareholders by realising its higher NAV through disposal or unbundling of its holdings. In other words, the company at any point in time would have been worth more to its shareholders broken up than maintained as a continuing operation.

How then is it possible to reconcile the fact that a share that consistently outperforms the market should be so consistently undervalued by the market? It should be appreciated that any business, including a listed holding company such as Remgro, is much more than the estimated value of its parts at any moment in time. That is to say a company is more than the value of what may be called its existing business, unless it is in the process of being unwound or liquidated. It is an ongoing enterprise with a presumably long life to come. Future business activity and decisions taken will be expected to add to the value of its current activities. For a business that invests in other businesses, value can be expected to be added or lost by decisions to invest more or less in other businesses, as well as more or less in the subsidiary companies in which the trust has an established controlling interest. The more value added to be expected from upcoming investment decisions, the higher will be the value of the holding company for any given base of listed and unlisted assets (marked to market) and the net debt that make up the calculated NAV.

Supporting this assertion is the observation that not all investment trusts sell at a discount to NAV. Some, for example the shares in Berkshire Hathaway run by the famed Warren Buffet, consistently trade at a value that exceeds its sum of parts. Brait and Rockcastle, listed on the JSE, which invest in other listed and unlisted businesses, are currently valued at a significant premium to their sum of parts. Brait currently is worth at least 45% more than its own estimate of NAV while Rockcastle, a property owning holding company offers a premium over NAV of about 70%. PSG, another investment holding company, has mostly traded at a consistently small discount to NAV but is now valued almost exactly in line with its estimated NAV.

It would appear that the market expects relatively more value add to come from the investment decisions to be made by a Brait or Rockcastle or PSG, than it does from Remgro. The current value of the shares of these holding companies has risen absolutely and relatively to NAV to reflect the market’s expectation of the high internal rate of returns expected to be realised in the future as their investment programmes are unveiled. Higher (lower) expected internal rates of return are converted through share price moves into normal risk adjusted returns. The expected outperforming businesses become relatively more expensive in the share market – perhaps thereby commanding a premium over NAV – while the expected underperformers trade at a lower share price to provide the expected normal returns, so revealing a discount to NAV.

The NAV of a holding company however is merely an estimate, subject perhaps to significant measurement errors, especially when a significant proportion of the NAV is made up of unlisted assets. Any persistent discount to NAV of the Remgro kind may reflect in part an overestimate of the value of its unlisted subsidiaries included in NAV. The NAV of a holding company is defined as the sum of the market value of its listed assets, which are known with certainty, plus the estimated market value of its unlisted assets, the values of which can only be inferred with much less certainty. The more unlisted relative to listed assets held by the holding company, the less confidence can be attached to any estimates of NAV.

The share market value of the holding company will surely be influenced by the same variables, the market value of listed assets and the estimates of the value of unlisted assets minus net debt. But there will be other additional forces influencing the market value of the holding company that will not typically be included in the calculation of NAV. As mentioned, the highly uncertain value of its future business activities will influence its current share price. These growth plans may well involve raising additional debt or equity, so adding to or reducing the value of the holding company shares, both absolutely and relative to the current explicit NAV that includes only current net debt. Other forces that could add to or reduce the value of the holding company and so influence the discount or premium, not included in NAV, are any fees paid by subsidiary companies to the head office, in excess of the costs of delivering such services to them. They would detract from the value of the holding company when the subsidiary companies are being subsidised by head office. When fees are paid by the holding company to an independent and controlling management company, this would detract from its value from shareholders, as would any guarantees provided by the holding company to the creditors of a subsidiary company. The market value of the subsidiaries would rise, given such arrangements and that of the holding company fall, so adding to any revealed discount to NAV.

It should be appreciated that in the calculation of NAV, the value of the listed assets will move continuously with their market values, as will the share price of the holding company likely to rise or fall in the same direction as that of the listed subsidiaries when they count for a large share of all assets. But not all the components of NAV will vary continuously. The net debt will be fixed for a period of time, as might the directors’ valuations of the unlisted subsidiaries. Thus the calculated NAV will tend to lag behind the market as it moves generally higher or lower and the discount or premium to NAV will then decline or fall automatically in line with market related moves that have little to do with company specifics or the actions of management. In other words, the market moves and the discount or premium automatically follows.

If this updated discount or premium can be shown to revert over time to some predictable average (which may not be the case) then it may be useful to time entry into or out of the shares of the holding company. But the direction of causation is surely from the value attached to the holding company to the discount or premium – rather than the other way round. The task for management is to influence the value of the holding company not the discount or premium.

Yet any improved prospect of a partial liquidation of holding company assets, say through an unbundling, will add to the market value of the holding company and reduce the discount. After an unbundling the market value of the holding company will decline simultaneously and then, depending on the future prospects and expectations of holding company actions, including future unbundling decisions, a discount or premium to NAV may emerge. The performance of Remgro prior to and after the BTI unbundling conformed very well to this pattern. An improvement in the value of the holding company shares and a reduction in the discount to NAV on announcement of an unbundling – a sharp reduction in the value of the holding company after the unbundling and the resumption of a large discount when the reduced Remgro emerged. See figure 1 above.

The purpose of any closed end investment trust should be the same as that of any business and that is to add value for its shareholders by generating returns in excess of its risk adjusted cost of capital. That is to say, by providing returns that exceed required returns, for similarly risky assets. Risks are reduced for shareholders through diversification as the investment trust may do. But shareholders can hold a well diversified portfolio of listed assets without assistance from the managers of an investment trust. The special benefits an investment trust can therefore hope to offer its shareholders is through identifying and nurturing smaller companies, listed and unlisted, that through the involvement of the holding company become much more valuable companies. When the nurturing process is judged to be over and the listed subsidiary is fully capable of standing on its own feet, a revealed willingness to unbundle or dispose of such interest would add value to any successful holding company.

This means the holding company or trust will actively manage a somewhat concentrated portfolio, much more concentrated than that of the average unit trust. Such opportunities to concentrate the portfolio and stay active and involved with the management of subsidiary companies may only become available with the permanent capital provided to a closed end investment trust. The successful holding company may best be regarded and behave as a listed private equity fund. True value adding active investment programmes require patience and the ability to stay invested in and involved in a subsidiary company for the long run. Unit trusts or exchange traded funds do not lend themselves to active investment or a long run buy and hold and actively managed strategy of the kind recommended by Warren Buffett. A focus on discounts to estimates of NAV, to make the case for the liquidation of the company for a short term gain, rather than a focus on the hopefully rising value of the shares in the holding company over the long term, may well confuse the investment and business case for the holding company, as it would for any private equity fund. The success of Remgro over the long run helps make the case for investment trusts as an investment vehicle. So too for Brait and PSG, which are perhaps best understood as listed private equity and highly suited to be part of a portfolio for the long run.

Appendix

A little light algebra and calculus can help clarify the issues and identify the forces driving a discount or premium to NAV

Let us therefore define the discount as follows, treating the discount as a positive number and percentage. Any premium should MV>NAV would show up as a negative number.

Disc % = (NAV-MV)/NAV ……………………………………….. 1

Where NAV is Net Asset Value (sum of parts), MV is market value of listed holding company

NAV = ML+MU-NDt ……………………………………………. (2)

Where NAV is defined as the sum of the maket value of the listed assets held by the holding company. MU is the assumed market value of the unlisted assets(shares in subsidiary companies) held by the holding company and NDt is the net debt held on the books of the holding company – that is debt less cash.

Note to valuation of unlisted subsidiaries MU;

MU may be based on an estimate of the directors or as inferred by an analyst using some valuation method- perhaps by multiplying forecast earnings by a multiple taken from some like listed company with a similar risk profile to the unlisted subsidiary. Clearly this estimate is subject to much more uncertainty than the ML that will be known with complete certainty at any point in time. Thus the greater the proportion of MU on the balance sheet the less confidence can be placed on any estimate of NAV.

The market value of the holding company may be regarded as

MV=ML+MU-NDt+HO+NPV………………………………………………..(3)

That is to say all the forces acting on NAV, plus the assumed value of head office fees and subsidies (HO)activity and of likely much greater importance the assessment markets of the net present value of additional investment and capital raising activity NPV. NPV or HO may be adding to or subtracting from the market value of the holding company MV.

A further force influencing the market value of the holding company would be any liability for capital gains taxes on any realisation of assets. Unbundling would no presumably attract any capital gains for the holding company. These tax considerations are not taken up here

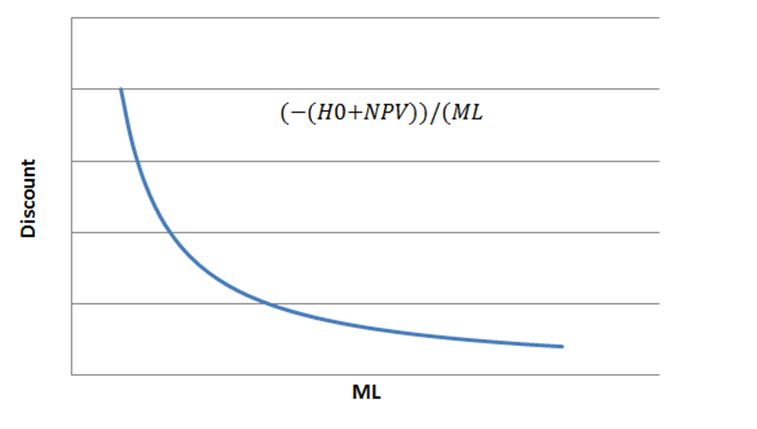

IF we substitute equations 2 and 3 into equation one the forces common to 2 and 3 ML,MU,NDt cancel out and we can conveniently write the Discount as the ratio

Disc= – (H0+NPV)/(ML+MU-NDt ) ………………………………………..(4)