We discuss government plans to encourage beneficiation of minerals. We argue that unwillingness to beneficiate is a market outcome rather than a market failure. We explain that is may well become a government failure as the price of the essential input for industry- electricity- is priced well above its true full cost. We argue against setting the price of electricity in South Africa to protect the balance sheet of Eskom rather than the promote the competitiveness of the economy. Click for full report

Electricity prices

Month: November 2011

The Rand this Q4 2011

This report discusses the recent behaviour of the ZAR- that is weaker than expected. According to our emerging equity market model of the ZAR. the ZAR is about 9% weaker than predicted by the model- indicaing recent SA specific influences on the ZAR.

For the full report click below

SA Operation Reverse Twist

Bond markets: Operation twist in reverse, or just bowling a wrong ‘un?

The US Federal Reserve System has been conducting operations to reduce the interest yield on long dated US Treasury Bonds, and by so doing attempting to twist the yield curve, that is buying longer dated bonds in order to reduce long term interest rates.

Meanwhile in SA, we are seeing something of a twist in reverse. We will discuss this topic further in this piece, but first some explanation of the US version.

The Fed has been borrowing short from its member banks to buy long dated US government debt. It has committed some US$400bn to the scheme. The Fed owns about US$1.675 trillion of US government debt or over 10% of all US debt in issue. It also holds US$841bn of mortgage backed securities issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government sponsored enterprises that support the mortgage market in the US. The Fed has been buying these securities in the market and the sums paid out have mostly ended up as excess cash reserves (deposits) held by banks with the Fed itself. What the Fed pays out has ended up with the Fed.

Mortgage loans in the US are typically long dated loans for up to 30 years, at fixed rates of interest linked to the yield on long dated Treasuries. The intention of the Fed is to reduce mortgage rates to encourage demand for homes and house prices. By so doing it would encourage a recovery in home building activity. Higher house prices would also help US households recover some of the equity they have lost in their homes.

According to US Flows of Funds Accounts published bty the Fed, the average US home is worth 30% less than it was in 2006. In 2005 homeowners’ equity in their homes (the difference between the market value of their homes and their mortgage liabilities) was worth over $13 trillion. The value of this equity had shrunk to $6.2 trillion by September 2011 and the share of owners’ equity in their homes from 59.8% to 38.6%. The net worth of US households has held up much better than their equity in homes over this period, having declined marginally from over $59 trillion in 2005 to $58.7 trillion in 2011. This represents 5.1 times the disposable incomes of households, which is a very high wealth to income ratio by international standards.

Without a recovery in the housing market, the prospects for US economic growth cannot be regarded as promising: hence Operation Twist. Long term interest and mortgage rates have remained exceptionally low, presumably mostly attributable to the safe haven status of US government debt in a highly risk averse world, rather than to Operation Twist itself or the quantitative easing (purchases of bonds and other securities) already conducted by the Fed.

And so to the reverse

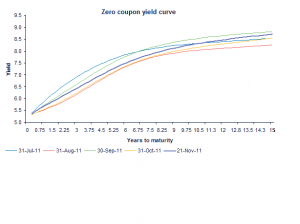

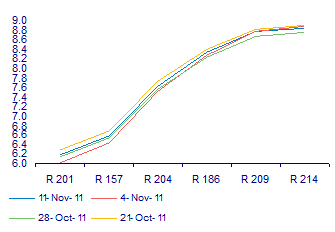

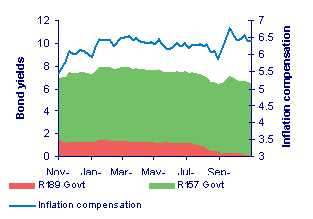

The SA Treasury has also been conducting its own intervention in the market for SA government debt. This may be described as the reverse of operation twist. The Treasury has been very busy extending the maturity profile of RSA government debt, actively buying up short dated government securities before due date and issuing much long dated securities of both the conventional and inflation linked variety. With the yield curve in SA upward sloping and getting more so (see below) this means that for now, or until the yield curve turns flat or negative, the SA taxpayer is paying up to 2% per annum more for its longer term borrowing. This additional expense of servicing interest bearing domestic rand denominated debt of the order of R800bn might well be better incurred helping the poor or giving tax relief to businesses to employ them. Why then the rush to roll over RSA debt before it matures and especially to convert lower interest short term debt to higher longer dated debt, before it is required to do so?

Source: Investec Securities and Investec Wealth and Investment

The average duration of SA debt, that is the time it takes for investors to recover their capital through a mixture of coupon payments and principal repayment, has risen significantly over recent years as we show below. Zero coupon bonds issued at a discount have a duration equal to the time to maturity. For debt with a predetermined coupon, the higher the nominal coupon payment, the shorter the duration. The average duration of US government debt is shorter than RSA debt – somewhere between four and five years.

Were these refinancing operations of the SA Treasury being conducted in the vanilla bonds alone, one might conclude that the Treasury, in preferring long to short, had a negative view on the inflation outlook for SA. Borrowing long is a good idea when inflation turns out to be unexpectedly high – borrowing short makes sense when the market overestimates the inflation rate incorporated into long term interest rates.

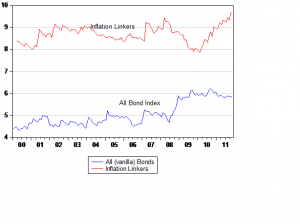

However the opposite is true when issuing inflation linkers and the Treasury has been especially aggressive converting its short dated inflation linkers into much longer dated inflation linkers. If inflation was expected to rise above expectations, an issuer would much prefer issuing short dated inflation linked securities, rather than the longer dated maturities. These long dated linkers would bring ever higher interest payments and receipts as inflation rose.

At recent auctions the Treasury has been issuing inflation linkers with 20 years to maturity (for example the R202) at real yields of 2.6% to redeem the once dominant R189 that is due to mature in 2013. The R189 is currently priced to offer a negative real yield of -0.07%. Or in other words, the Treasury is now paying out something like 240bps extra to roll over this inflation linked debt, rather than waiting for this shorter term debt to mature in two years time.

Average duration of RSA Inflation and Vanilla Bonds

Why Europe is not a good example

Why then would the Treasury be pursuing such aggressively expensive debt management? Hopefully it is not in response to the difficulties European governments and their debt managers have been seen to have in rolling over their debt with highly bunched maturity schedules. These refinancing difficulties arise because the Greek, Portuguese, Italian and Spanish governments cannot call upon the services of their own central banks to convert, without limit, interest bearing into non-interest bearing government debt- that is to say cash. Their central bank sits in Frankfurt and appears very reluctant to convert longer dated Euro debt into cash. This is not a problem for the US. If faced by any temporary reluctance to bid for longer dated Treasuries, the Fed could come to the rescue with extra cash.

So could the SA Reserve Bank, if called upon, issue rands in exchange to overcome any refinancing emergency that might show up. Rolling over debt can only become a solvency or liquidity problem when the borrowing is undertaken in a foreign currency. Rolling over debt cannot be an issue when the debt is issued in an inconvertible currency that can be created without limit by a central bank should this be forced upon a government with its independent central bank. And most important, the knowledge that in last resort, government debt issued in the inconvertible currency of the land can always be converted in to cash, would surely be enough to fully overcome fears that government debt could not be rolled over. By exchanging cash for government securities (if conducted without limits), a central bank could invoke an inflation problem. However it could also overcome any refinancing problems (as the Italians and Greeks, now without such a fallback position, are fully aware).

There is presumably a case for smoothing what may be bunched repayment schedules for maturing government debt. But there is also a case for anticipating them in advance when scheduling debt, to avoid bunched repayments making such smoothing operations unnecessary in the first place. Paying a large interest premium to do so does not make good sense; nor is long dated debt issued by the RSA necessarily superior to issuing shorter dated debt.

Long term interest rates are the geometric average of expected short rates over the same period. To think otherwise is to second guess the market in fixed interest and there is little reason to believe the issuers of debt have superior insight about the direction of interest rates than lenders have. There are however some unintended consequences of longer duration: the longer the duration the more responsive the All Bond Index will be to unexpected changes in interest rates. Adding risks to fixed interest rate bonds in general discourages demand for them.

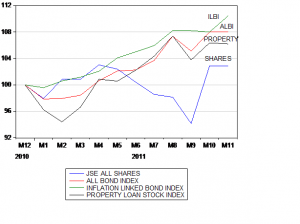

Furthermore the recent debt management operations in the inflation linkers (which have meant additional demand for them) have made this class of bonds an outperformer over the past year. Is the SA Treasury, in its urgency to substitute long dated for short dated RSA securities (to avoid what it regards as potential embarrassments in the debt market), misreading the nature of the Euro debt problems – at the expense of the SA taxpayer? Brian Kantor

Asset Class Performance 2011 to November 18th

The Reserve Bank – what it can and cannot do

Published in Sunday Independent November 20th 2011

Brian Kantor

15th November 2011

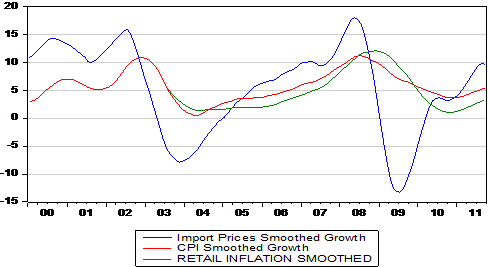

It is surely clear that the SA economy can do with all the help it might get from lower interest rates. It is not getting that help from the Reserve Bank because the inflation outlook has deteriorated. The inflation outlook however has deteriorated because of a weaker rand. And the rand is weaker for reasons completely out of the influence of the MPC – that is the Euro debt crisis.

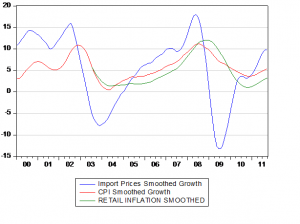

The MPC should know but seems not to recognize that interest rate settings in SA have no predictable influence at all on the exchange value of the rand. The correlation between changes in interest rates and the changes in the value of the rand is close to zero- that is there is no observable influence of changes in interest rates on the exchange value of the rand. And therefore interest rates have no predictable influence on the prices paid for imported and exported goods that have such a strong direct bearing on consumer prices in South Africa. Moreover over the past twelve months, since the MPC last cut interest rates, the rand has been all over the place, driving inflation in one and then the other direction.

The evidence is overwhelming, no doubt awful to contemplate for those with a text book view of monetary policy in South Africa is that interest rates and therefore monetary policy settings have not had any meaningful influence on inflation outcomes in SA. And moreover they cannot be expected to have any predictably anti inflationary purpose until the rand responds to SA, rather than global forces. This surely cannot be predicted to happen any time soon.

Like it or not monetary policy can only influence aggregate demand in South Africa. Its impact on the price level has been and will be overwhelmed by moves in the rand. Thus higher interest rates, especially when accompanied by a weaker rand and the higher prices that follow, can only mean less spending and less output and employment in South Africa- without having any helpful influence on inflation or the outlook for inflation that will be dominated by the outlook for the rand. By not lowering rates or even, heaven forbid at this stage of the business cycle, contemplating raising them, because the inflation rate might breach the inflation targets, the MPC has burdened the SA economy with less growth and no more or less inflation.

And should the Reserve Bank response to this critique take the form that monetary policy must fight not just inflation but inflationary expectations, it should also be recognized that there is also no evidence of this in South Africa. Inflation may have affected inflation expected in South Africa, even though inflation expected has been remarkably stable, suggesting that such effects have been of small magnitude. But there is no evidence of any feedback or so called second round effects effects. That is more inflation expected leading to more inflation. This has not happened perhaps because the theory is faulty but much more obviously, because inflation in SA follows the exchange rate and does not lead it. ( See Below)

South Africans have been called upon to make sacrifices in the form of slower growth for lower inflation or at least inflation in line with inflation targets that in the light of our recent monetary history make no sense at all. A new narrative for SA monetary policy is long overdue. This does not have to mean more inflation or more inflation expected. This would neither be desirable or inevitable. If the narrative explains the facts of the matter that inflation is dominated by exchange rate movements, over which SA has little predictable influence, and monetary policy was set accordingly, it would mean faster and more sustainable rates of growth. This faster more sustainable and predictable growth would attract more capital to South Africa to fund this growth. This would mean a stronger rather than weaker rand over the long run- and so less rather than more inflation over the long run.

But this narrative would mean recognizing that inflation targeting for South Africa- given the openness of its financial and currency markets to unpredictable global forces – has not been a sound basis for monetary policy.

Retail inflation- led by import prices – a mix of global prices and exchange rates – heading higher

Earnings are growing strongly in Europe – despite slow growth

Alexis Xydias and Adria Cimino report for Bloomberg today that

“Net income for companies in the Stoxx Europe 600 Index will rise by 10.5 percent in 2012 after increasing 11 percent this year, led by carmakers such as Porsche SE and retailers including Burberry Group Plc, according to more than 12,000 analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg. The gauge is headed for four straight years of income growth exceeding 10 percent, the longest streak since 1998, data show”, and that European profit growth

“….. will exceed the 10.1 percent estimated for U.S. companies, even though the economy in the 17-nation euro zone is expanding at one-third the pace….”

The reason that profits are growing much faster than nominal GDP in Europe and the US is that the dominant European and US companies increasingly depend on revenues and profits generated globally. Emerging market economies are doing much better and growing much faster than developed economies. They are playing catch up adopting proven technologies and through the absorption of labour from low productivity employment in agriculture to much more productive engagements in factories that fully participate in global supply chains without push back from trade unions protecting established workers. Yet wages are rising rapidly as competition for workers builds up. And these fast growing economies have not yet made promises of welfare benefits funded by taxpayers that are now proving impossible to fulfil. The cloud on their economic horizons is a meltdown in demands from Europe and perhaps the US- where the economic outlook now looks a lot more promising than a few months ago. The opportunity these rapidly emerging economies have is to rely much more on domestic rather than foreign consumers.

It is these same consumers in the emerging economies that are already proving so helpful to the profits of companies listed in Europe and the US. The willingness of these profitable global companies to add productive capacity and to employment in their home economies would be greatly assisted by a sense that their own governments are coming to grips with the necessity to spend less so as to grow faster and in this way overcome their debt problems

Interest rates: Surprise, surprise – SA specific (monetary policy) risks influence the JSE and the rand

Our markets have been dominated by global events – with the JSE, the rand and to a lesser extent the SA bond market gyrating closely in tune with global markets, especially emerging markets, in response to degrees of global risk aversion.

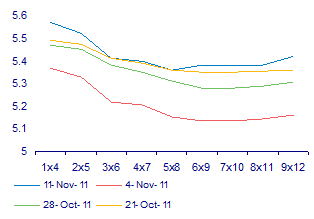

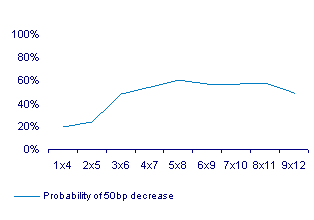

Friday 11 November however was an unusual day in the SA bond and equity markets. Market moves were dominated by an SA specific event: the meeting and outcome of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Reserve Bank that reported back on Thursday afternoon. The market by Friday had significantly revised its view on the interest rate outlook. The market had attached only a small probability of a cut in rates on the Thursday before, but had been pricing in an above 50% probability of a cut within three months.

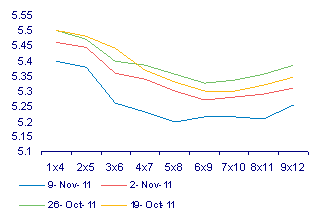

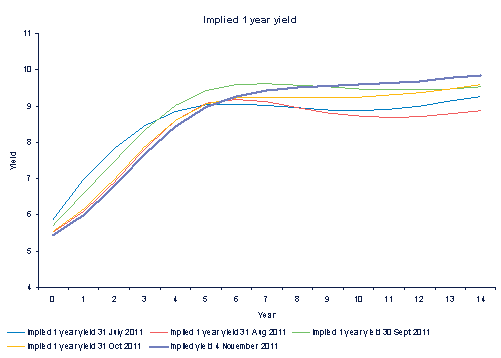

As we show below the market, in the light of what was said rather than what was decided at the MPC meeting, now regards the chance of a cut in rates anytime soon as highly remote. The yield curve that was upward sloping, indicating the likelihood of higher interest rates a year out, has shifted up and become steeper indicating higher rates to come, and sooner.

Clearly such expected interest rate moves are not helpful to the growth outlook for SA, which has if anything deteriorated in recent months, with the risks attached to Europe and its implications for global growth, as was confirmed by the Reserve Bank. Also indicated by the Reserve Bank was the weakness in domestic demand.

Hence the failure on Friday of the equity market to respond to better news about Europe or to the strength in offshore equity markets. The rand was similarly unmoved by stronger equity markets, perhaps also because the SA growth outlook had deteriorated.

It is surely clear to all on the MPC that the SA economy can do with all the help it might get from lower interest rates. It is not getting that help because the inflation outlook has deteriorated. The inflation outlook however has deteriorated because of a weaker rand; the rand is weaker for reasons completely out of the influence of the MPC, namely the Eurozone debt crisis.

The MPC should know but seems not to recognise that interest rate settings in SA have no predictable influence at all on the exchange value of the rand. As we show below the correlation between changes in interest rates and the changes in the value of the rand is close to zero – there is no observable influence of changes in interests rates on the exchange value of the rand and therefore on the prices paid for imported and exported goods that in turn have such a strong direct bearing on price setting behaviour in SA. The correlation co-efficient is close to zero. Moreover, since the MPC last cut interest rates in November last year, the rand has been all over the place driving inflation in one and then the other direction.

The evidence is overwhelming that interest rates have not had any meaningful influence on inflation outcomes in SA. Moreover they cannot be expected to have any predictably anti-inflationary purpose until the rand responds to SA, rather than global forces. This surely cannot be predicted to happen any time soon.

Like it or not monetary policy can only influence aggregate demand in SA. Its impact on the price level has been and will be overwhelmed by moves in the rand. Thus higher interest rates, especially when accompanied by a weaker rand and the higher prices that follow, can only mean less spending and less output and employment – without perhaps having any helpful influence on inflation or the outlook for inflation. By not lowering rates or even, heaven forbid, contemplating raising them, the MPC has consistently burdened the SA economy with less growth without any predictable influence on inflation.

And should the response to this critique take the form that monetary policy must fight not just inflation but inflationary expectations, it should also be recognised that there is also no evidence of this in South Africa. Inflation may have affected inflation expected in SA (even though inflation expected has been remarkably stable, suggesting that such effects have been of small magnitude). But there is no evidence of any feedback effects (ie more inflation expected leading to more inflation). It has not happened perhaps because the theory is faulty but much more obviously, because inflation in SA follows the exchange rate and does not lead it.

South Africans have been called upon to make sacrifices in the form of slower growth for lower inflation or at least inflation in line with inflation targets, which make no sense at all. A new narrative for SA monetary policy is long overdue. This does not have to mean more inflation or more inflation expected. If the narrative recognises and explains the facts of the matter and monetary policy were set accordingly it would mean faster and more sustainable rates of growth. By attracting more capital to SA to fund growth could mean a stronger rather than weaker rand over the long run and so less rather than more inflation over the long run. But this would mean recognising that inflation targeting – given the openness of its financial and currency markets to unpredictable global forces – has not been a sound basis for monetary policy in SA. Brian Kantor

If not now, then when?

We have heard the same story before from the Reserve Bank MPC. With every reason to cut rates to improve the growth outlook and to alleviate the risks of slow growth (as highlighted recently by Moody’s), the MPC again stood pat as it has done since November 2010, when it last cut rates in surely very different and less propitious circumstances.

Yes, as we are constantly reminded, the inflation rate remains stubbornly high despite the recognised weakness of domestic demand. But what is not acknowledged is that the inflation rate is beyond any predictable influence of the Reserve Bank. This fact of economic life is simply ignored by the MPC which employs a highly flawed theory (that enjoys no empirical support whatsoever from the SA evidence) of the forces that have driven inflation in SA over the past 10 years. The MPC appears simply not up to the intellectually demanding task of adapting its highly conventional theory of inflation to recognise its anti-inflationary impotence or the seriousness of the slow growth outlook. Its responsibility is to do what it can for growth (which is all the Reserve Bank can realistically hope to do), that is, influence the domestic growth rate with its interest rate settings so that it may better fall in line with potential growth.

The fact is that the exchange rate drives inflation in SA and the exchange rate is dominated by highly unpredictable global forces beyond the influence of SA monetary policy. Inflationary expectations have remained highly stable in SA and only modestly influenced by inflation itself. Any possible feedback from more inflation expected to more inflation has clearly not been in evidence. Moreover there has been no predictable impact of changes in policy determined interest rates on the exchange value of the rand. Therefore it should be recognised that while interest rate settings influence the level of aggregate demand in SA, the links between changes in aggregate demand and inflation have been overwhelmed by exchange rate changes (and will continue to be so overwhelmed). In the same way, any possible influence on the inflation rate of inflationary expectations will be overwhelmed by unpredictable exchange rate developments and to a lesser extent by global food and commodity prices. The so called second round effects on inflation are but an article of faith for the members of the MPC. Good monetary policy takes more than faith in conventional and also flawed theories of inflation.

This is a disappointment. We had hoped for better from Governor Marcus – but we are inclined to the view that we should not now expect a more growth sensitive approach from her and her committee.

It is very hard to anticipate the change in circumstances that could lead to a rate cut anytime soon. If not now then when? The inflation outlook will remain unchanged (absent of any important reversal in the rand) that can only come with an improved global growth outlook that in itself would reduce the argument for lower rates. And so we can anticipate an extended period of sub-optimal growth, inflation at or about the upper band of the target range – and thus an extended period of interest rates at current levels. Brian Kantor

SA economy: Moody’s can do some good

The mood may have changed even if the SA economic facts have not. But the Moody’s negative watch can do SA good without doing any harm.

Moody’s has raised legitimate concerns about the risks facing economic policy makers in SA that will resonate strongly with observers not only outside but also inside government circles. The question one would have to ask is what is especially new about these threats to SA political and economic stability. Perhaps the Moody’s decision to put SA’s credit rating on negative watch tells us more about the changing world of credit and especially for credit rating agencies than it is does about the direction of SA economic policy. What is clearly especially galling to the Treasury is that Moody’s appears to have been unimpressed by the strong affirmation of the conservative fiscal policy settings outlined by Finance Minister Gordhan in his speech to Parliament in October backed up in his recently issued Medium Term Budget Policy Statement. The government has planned to maintain the ratios of government revenue and government expenditure to GDP, to reduce debt to GDP ratios and to give greater impetus to capital formation rather than improved benefits for those who work for or depend on government.

The populist threats to the conservative setting of fiscal policy or the all-important role played in the economy by privately owned businesses, both domestic and foreign, are not new and will remain an ever present in SA, as they will almost everywhere else (Switzerland perhaps excepted and Wall Street Masters of the Universe not excluded) . The greatest risk to stability in SA is slow rates of economic growth that frustrate ambitions of individuals and firms and the financial capacity of the public and private sectors. This can lead to attempts at quick fixes by politicians.

The rating agencies have long been very well aware of these dangers to the impressive conservative fiscal and monetary policy directions taken by the new SA. Aware enough, that is, to have made SA’s ascent to an investment grade credit status a long hard ride. It is this status that has now been put on negative watch by Moody’s (though not by Standard and Poor’s). But Moody’s was not entirely negative in its judgment. It did not derate RSA credit, for the following reasons as we quote below from its statement:

“To date, South Africa’s fiscal picture and economic policy parameters have remained generally in line with Moody’s expectations, hence the continued A3 rating. The South African authorities’ economic stewardship has been effective for more than a decade, during which time they brought public finances and inflation under control and significantly bolstered the country’s external liquidity position. In addition, meaningful progress has been made in raising living standards, expanding social services and physical infrastructure, and putting in place a financial support mechanism for the most underprivileged. Finally, the outlook for South Africa’s public finances has not diverged significantly from Moody’s projections when the country entered into recession in 2009, roughly the time of Moody’s last sovereign rating action, despite the rather sluggish economic recovery over the past two years….”

The Moody’s rationale for a negative watch on RSA credit went as follows and is highly deserving of serious attention especially by those in the tripartite alliance inclined to believe in quick fixes or the magic wands that are meant to provide well paid jobs for all (that current policies applied to regulate the SA labour market have so singularly And conspicuously failed to do), a fact of SA economic life well recognized incidentally by Minister Gordhan in his policy review.

To quote the rationale:

“The primary driver behind Moody’s decision to change the outlook on South Africa’s government ratings to negative is the rising pressure from society at large, as well as from within the ANC and its political partners, to ease fiscal policy in order to address South Africa’s high levels of poverty and unemployment. In Moody’s view, spending beyond the substantial amounts already budgeted in response to such demands could push debt to levels more commensurate with lower-rated sovereigns. South Africa’s direct debt and guarantees for state-owned companies’ obligations currently approach or exceed 50% of GDP. Moreover, a substantial proportion of the government budget is already absorbed by wages, social support and debt service, limiting the room for new growth-supportive spending.

“Secondly, Moody’s is concerned that economic growth will be somewhat slower than previously expected in the years ahead due to a weaker global economy, depressing any rebound in South African employment levels over the coming years. This would in turn aggravate existing frustrations over the lack of economic opportunities. Moreover, job creation in this environment would not be enough to absorb new entrants to the labour force nor reduce the already high levels of unemployment. In Moody’s opinion, this situation poses risks to political stability over the longer term. Thirdly, Moody’s believes that the political leadership’s unwillingness to definitively reject demands from certain segments of the political spectrum for more activist policy interventions is harmful to South Africa’s economic prospects, in particular private investment. The agency also says that nationalisation of the mines and/or other sectors — however unlikely to happen — would not achieve the stated aim of accelerating progress on black economic transformation. Instead, such moves are more likely to do the opposite, reducing the country’s attractiveness to both local and foreign investors, and encouraging the outward migration of citizens and businesses. Such actions would in turn raise the risk premium on government debt, further inflating the already-rising costs of debt service. Overall, Moody’s believes that the next two years will be especially challenging for South Africa’s political system, with the potential for further pressures emerging for the established economic policy framework during this period.”

The most important factor restraining growth in SA over the next 12 months are not the structural weaknesses of the SA economy or the populist threat to property rights and fiscal policy settings. It is the European government debt crisis and the threat it poses to global growth and sothe demand for SA goods and services, including services supplied to tourists. The behaviour of the rand and so the outlook for inflation and its impact on interest rates paid on debt issued by the RSA is completely dominated by these global forces. RSA specific political or monetary policy influences on these important influences on the growth outlook and the willingness of SA firms and households to invest or spend are conspicuously absent. It is not the Moody’s watch that moved the rand yesterday but higher yields on Italian government debt.

Hopefully these facts of economic life have been well appreciated at the Reserve Bank sitting today to decide on the repo rate. As the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank pointed out in its latest statement, the SA economy is being held back by a lack of foreign and domestic demand. The short term outlook for the global economy has deteriorated. The outlook for the domestic economy is not conspicuously improved, at least according to Moody’s. The Reserve Bank can only hope to stimulate domestic demand by lowering interest rates. It cannot expect to have any predictable influence on foreign demand or the value of the rand (and so on the outlook for inflation) with its interest rate settings.

That lowering interest rates might do some good in promoting essential economic growth and so reducing SA risks (without doing any harm in the form of more inflation) should make a decision to cut interest rates an obvious one. If it was not altogether obvious at its last September meeting, it should be obvious today. And the Moody report would, it may be hoped, have made it even more obvious: the risks to the SA economy are not inflation (over which the Reserve Bank has no influence in the short term) but to growth, over which interest rate settings may have some influence. However the market place yesterday was not expecting a 50bps cut. This is despite the short term Forward Rate Agreements having shifted significantly lower over the past week, raising the probability of a 50bps cut to over 50% within three months. The probability of a cut today was still only about 20%.

We can hope the Reserve Bank will get it right and that the market has misread its better intentions. Brian Kantor

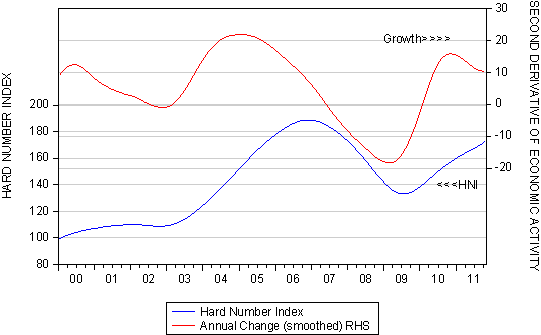

Hard Number Index: Noteworthy change

The economic signs from the Hard Numbers in October (vehicle sales and the note issue) provide some encouraging confirmation of the improving state of the SA economy.

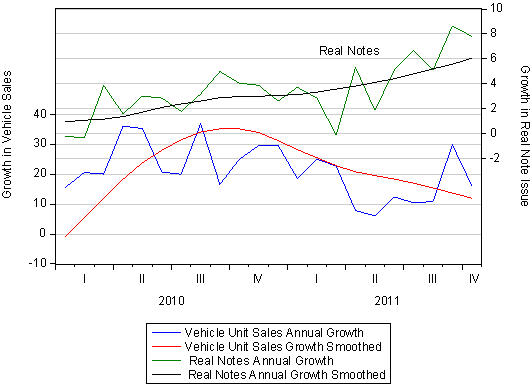

The Hard Number Index of Economic Activity in South Africa (HNI) continued its upward trajectory in October. This indicates that the economy – based on two hard numbers for October, unit vehicle sales and notes in circulation – maintained a positive rate of growth in October. The direction of the economy (forwards or backwards) is shown by the HNI: when it moves higher the economy is moving ahead; when lower it is going in reverse. The economy, according to these up to date and hard numbers, is clearly moving ahead. The speed at which the economy moved ahead in October may however have slowed down, as we show below.

The changing speed at which it moves forward is indicated by the growth in the HNI. The speed of the economy slowed because vehicle sales in October 2011, while very strong compared to a year before, were down on September sales that were extraordinarily strong that month. However the other half of the HNI is made up of the notes issued by the Reserve Bank. These are issued in response to the demand for notes by banks and the public adjusted for the CPI. These growth rates have picked up very strongly in recent months. (See Below)

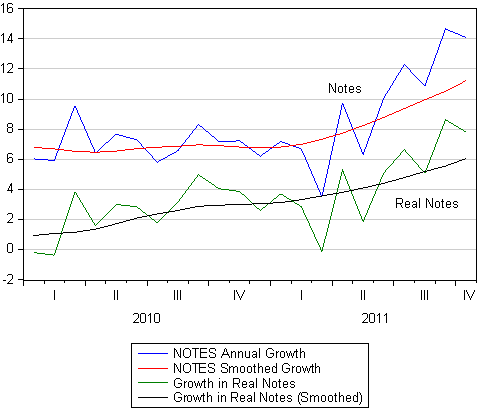

It may be seen below that the demand for and supply of notes has picked up significant momentum this year and that the pace at which notes are being issued is accelerating. Notes are held by banks in their branches and ATM machines and by the public in their wallets and purses to facilitate their spending intentions. It would therefore appear that at month end October, spending was gaining momentum. These trends will have to be confirmed but only much later by official estimates of retail activity. The most recent statistic of this kind for the retail sector is only for August 2011. These latest indicators confirm for us that the economy, after a slower patch in the second quarter, has picked up momentum.

The Reserve Bank however has never seemed to regard the narrow or broader definitions of the money supply and its growth as an objective of policy or of interest rate settings. Its decisions to lower short term interest rates at its meeting this week not are unlikely to be influenced by the accelerating growth in the note issue. Furthermore the growth in broader money (to September 2011) remained rather modest when viewed on a year on year basis. This may be so, but if interest rates are cut this week, this may add some pro-cyclical impetus to monetary policy. Brian Kantor

Interest rates: Inflation now and into the future

The SA chances of an interest rate cut have improved markedly. Insuring against the risks of more inflation has also become more expensive. What does this mean for equities?

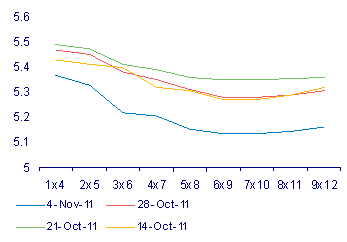

This week the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Reserve Bank will meet to set the Bank’s repurchase (repo) rate. Their deliberations were preceded last week by a very sharp downward shift in the Forward Rate Agreements (FRAs) set by the commercial banks. These rates, at which the banks are willing to lend for three months in three months’ time and beyond, indicate the direction of the repo rate to be set by the MPC.

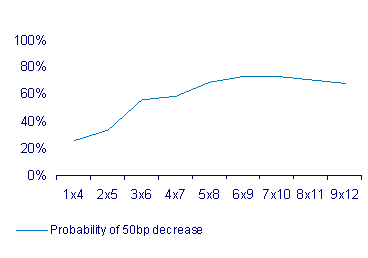

With the bodily shift of the FRA curve lower and the negative tilt of the FRAs, the SA banks have significantly raised the prospect of a cut in short term interest rates in the near future. This probability can be inferred from the level and direction of the forward rates. As we show below the probability of a 50bps reduction in short term interest rates is about 20% this week, rising to over a 70% chance of a cut within six months.

We had judged that the MPC had come very close to cutting rates at its last meeting, having every good reason to do so, given that the economy had been operating well below its potential. But the MPC then blinked and passed on the opportunity. Since then the MPC would have noticed how the Australians and the Europeans have cut rates with a deteriorating global and European growth outlook.

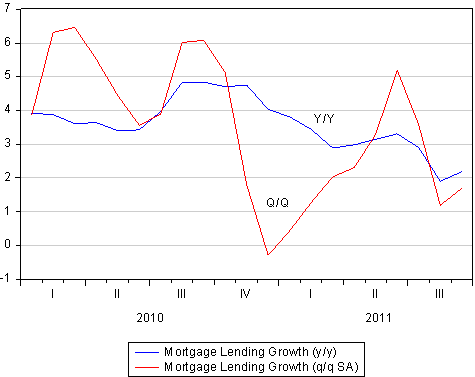

However the rand has not regained the ground it was losing at the time of its last meeting and so the SA inflation outlook will not have improved. Our sense as we have reported from retail and vehicle sales and the growth in cash, is that the local economy has picked up some momentum, even as the global outlook has deteriorated. But any incipient recovery has not been rapid enough to suggest that the gap between actual and potential GDP growth will have closed in any significant way. The housing market in SA has not shown any signs of a recovery in demand or house prices – meaning accompanying weakness in bank lending and, more important, construction activity and the employment that comes with construction and the renovation of homes.

Thus the case for lowering the repo rate is as strong as it was. The question is whether the MPC have had time to gain courage and take the leap to lower interest rates. As indicated such a leap will not come as a complete surprise to the market place.

The outlook for interest rates over the longer term has also changed to a degree. Implicit in the term structure of interest rates is that one year rates will now be lower than previously thought until year five and to be higher thereafter. The yield curve is accordingly steeper – lower interest rates for now but higher over the long term.

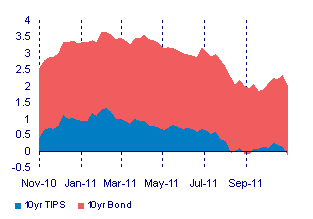

This also indicates that the market expects inflation to rise rather than fall over the next 10 years. And so investors in SA, as elsewhere, are prepared to pay up for insurance against higher inflation in the form of accepting much lower (even negative) yields on medium dated inflation linked bonds. The yield on the key 10 year inflation linked US bonds (TIPS) has turned negative again while the benchmark inflation linked RSA bond (the R189) that matures in March 2013 now offers a minimal 5bps yield – meaning that investors are being offered an extra and seemingly attractive 6.5% a year to carry inflation risk over the next few years. The bond market in the US is indicating that over the long term inflation will average about 2% a year. Given all the cash pumped into the US monetary system, but now idle on the balance sheets of banks, and all the cash pumped into and still to be pumped into the European banks, there must be a wide distribution of possible inflation outcomes about this benign 2% average. Hence the low inflation linked yields and the high price of gold (and also by comparison with lower interest rates, both real and nominal, the relatively low costs of entry into equity markets).

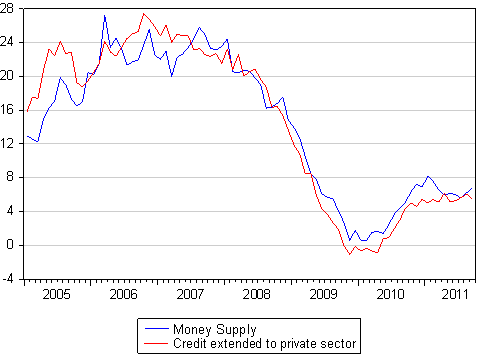

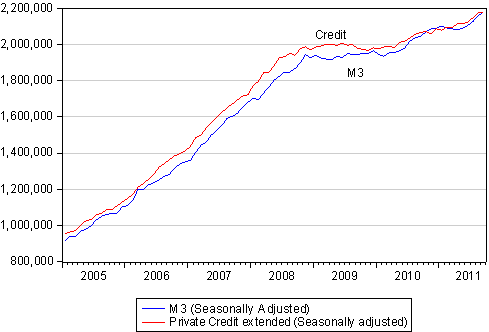

Money supply and credit growth: Confirming a more positive picture

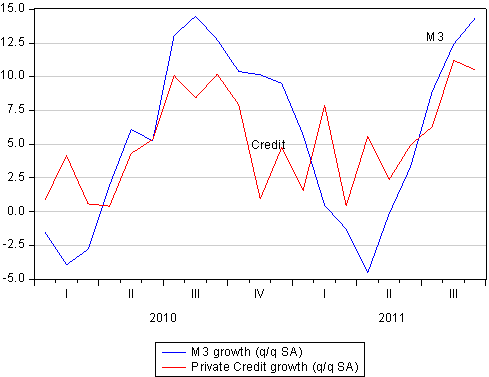

Money supply and bank credit numbers have been updated to September 2011. The year on year growth rates have recovered from their cyclical lows of late 2009 but appear to have stabilised in the 6% range. Broadly defined money supply covers almost all of the liabilities side of the balance sheets of the banks; while credit extended to the private sector accounts for almost all of the assets held by banks and so the growth rates are bound to be almost identical.

A closer look at the bank statistics over the past three months reveals a somewhat more encouraging picture. On a seasonally adjusted basis both money supply (M3) and bank credit have picked up momentum.

When these statistics are converted into a rolling quarter to quarter annualised rate of growth we observe a strong recovery to growth rates of +10% from the slower rates of growth realised earlier in the year.

Mortgage credit demanded and supplied (accounting for about half all bank lending) however remains highly subdued, with growth rates tending lower rather than higher. House price inflation leads mortgage credit supplied and it would appear that the housing market remains in the doldrums.

The money supply and credit trends confirm our impression from vehicle sales, activity at retail level and the growth in the narrowly defined money supply (notes in circulation) that the SA economy has rather more life in it than is perhaps generally recognised. We await data on the note issue and vehicle sales in October, due to be released this week to give us a more up to date impression of the current state of the economy.