14th July 2020

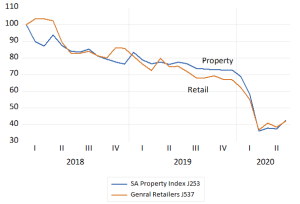

The SA bond market reacted sharply to the spread of Covid19 and the ever more likely prospect of a damaging economic lock-down. Long term interest rates were pushed higher earlier in 2020 in response to SA’s deteriorating fiscal trends even before the full damage to be caused by lock-downs to the economy and the budget deficits were recognized. Long rates then reversed as the crisis in financial markets passed by with lots of aid form central banks in the developed world. However the gap between long and short yields in SA had widened sharply and remained very wide, despite the bond market recovery, as the Reserve Bank cut its repo rate.

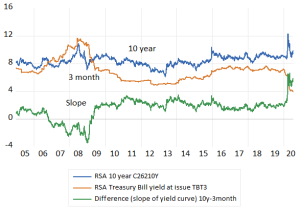

Fig. 1; RSA long and short rates Daily Data 2015-2020- July 10th

Source; Bloomberg, Iress, Investec Wealth and Investment

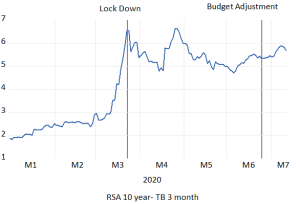

The RSA ten-year bond currently (July 10th) yields 9.67% p.a. while the yield on a three month Treasury Bill is 3.96% p.a. a positive spread of 5.67% p.a. This means that the slope of the yield curve is far steeper than at any time over the past 15 years. close to 10% p.a. Another way of putting this is that the SA taxpayer has to pay an extra 5.67% p.a. to borrow long rather than short.

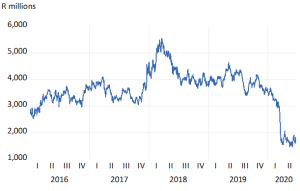

Fig.2: The slope of the RSA yield curve; 10 year – 3 month yields. Daily Data 2020 to July 10th

Source; Bloomberg, Iress, Investec Wealth and Investment

On the face of it this would appear to be a very expensive exercise for the SA government to borrow for a longer-term rather than to roll over short term debt. Given the current strains on tax revenues and the rapidly widening fiscal deficit and the government borrowing requirements is it a choice the Treasury is likely to exercise? Or is it going to finance a much greater proportion of its growing debt at the cheaper short term end of the term structure of interest rates? We think the answer will be and should be yeas to this question. We will attempt to provide more insight as to the borrowing choices the SA Treasury is likely to exercise over the coming months and years.

The answer is perhaps less obvious than it appears at first glance. The expectations theory of interest rates would posit, with very good reason, that the long-term rate is but the average of the expected short term rates over the period of any loan. Hence in principle there would be no good reason to prefer long over short-term lending or borrowing. Borrowing long or short and having to roll over shorter term debts should be expected to turn out about the same for borrowers or lenders with choices.

However, if interest rates at the short end rise faster than expected, borrowing long (and lending short) would turn out to be the better option. And vice versa if interest rates were to rise less than expected borrowing short and then rolling over short term debt would have been the better option. As would lending long.

The chances of unexpected fast or slow increases in short rates over the relevant period must be about the same- if the market behaves consistently with the consensus of expectations. Choosing to borrow short or long or lending long or short, given the freedom to choose either option, then represents speculation, the belief that the borrower or lender can beat the market, a belief that may turn out right or wrong- with the same probabilities- given the rationality of the expectations of interest rates.

This notion of equilibrium in the capital market surely makes sense, lenders and borrowers with the option to lend or borrow for shorter or longer periods would presumably expect to pay out the same or earn the same, one way or the other. If you could lend or borrow for three months at a time or for six months at an agreed rate today the expected interest, to be received or paid out over two consecutive three-month periods must presumably be the same as the interest rate fixed for six months. Thus the average (compounding) interest received or paid if the contract was fixed for three months at a known rate and then re-negotiated after three months at a rate, only to be known in three months time, must be expected to be the same. If the current three- month rate is below the six-month rate then it follows that the three months rate in three-months must be expected to rise to make the expected returns on the interest paid or received equivalent.

If this is not the case there would be every incentive to borrow or lend for longer or shorter periods depending on which was expected to suit better. It is the attempts to minimize or maximise interest paid or received that eliminates any such obvious market beating opportunities.

Thus according to the theory, if the three-month rate is below the six-month rate, then the three- month rate must be expected to rise above the current fixed six month rate in order to average out at the higher rate. Thus a positively sloped yield curve, long rates above short, implies that short rates are expected to rise above the current longer term rate over the duration of the lending and borrowing contract. And vice-versa if the yield curve is sloping downwards, short rates must be expected to fall below the alternative longer fixed-term rate. The same logic applies to longer term contracts. If the ten year RSA bond yield is above the yield on a five year bond, the five year bond yields will be expected to rise over the ten year period enough to provide the same expected, compounding, average return.

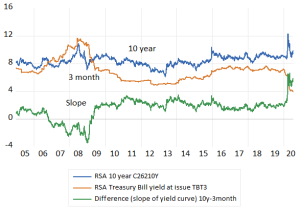

The RSA yield curve has had a consistently positive slope since 2005 with the exception of the boom period of 2006-2008 when short rates rose sharply and the rapid growth in the economy was clearly expected to slow down and bring lower short rates with it. As transpired with the aid of the Global Financial Crisis and the recession in SA that followed. As may be seen in the figure below the slope of the RSA yield curve has been at its most positive in 2020. It would therefore for almost all of this period been helpful to have borrowed short rather than long.

Fig.3; Long and Short Term interest rates in SA and the Slope of the Yield curve. Daily Data 2005- July 10th 2020.

Source; Bloomberg, Iress, Investec Wealth and Investment

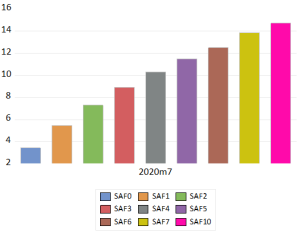

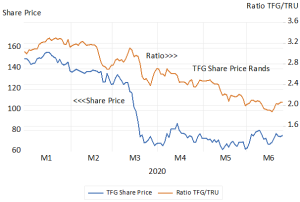

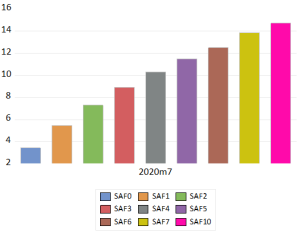

The slope of the term structure of interest rates, the differences between longer and shorter yields, allows us to interpolate the shorter-term interest rates expected in-between. Thus for a portfolio manager at a SA insurance company to prefer the 3.44% p.a. received currently for a 12 month RSA Treasury Note Bill rather than the 7.07% on offer for a RSA bond fixed for five years, or the fixed 10.05 % p.a. available from a ten year RSA bond, must mean that the one year yield is expected to rise sharply over the next five or ten years. That is to make lending short rather than long the sensible choice to make.

To provide equivalent returns lending long or short and rolling over each year the one year rate (now 3.4%) would have to more than doubled to 7.31% in two years. Then increased further to 8.91% after three years and then on to to 11.5% after five years. After ten years the one-year rate would need to be as much as 14.75% to make preferring one-year loans to five or ten year ones the sensible decision. (See figure below)

Fig.4; RSA one year (forward rates) implicit in the current slope of the yield (for on to ten years)

Source; Thompson-Reuters, Investec Wealth and Investment

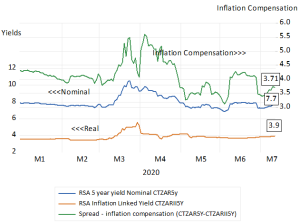

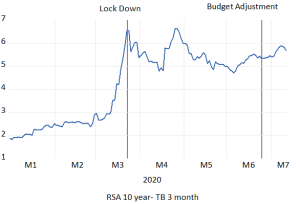

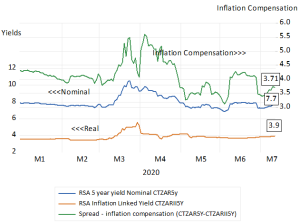

It is very difficult to reconcile such expectations with the likely reactions of the Reserve Bank over the next few crucial years. The outlook for GDP growth is very grim and the expectations for inflation over the next few years remain highly subdued. The compensation for taking on inflation risk in the RSA bond market is currently only an extra 3.9% p.a. to be earned over five years. That is 3.9% is the extra yield available from a nominal 5 year bond over its inflation protected alternative.

Fig.5; RSA nominal and real 5 year bond yields and their spread- inflation compensation for five years.

Source; Bloomberg, Investec Wealth and Investment

Therefore if we subtract this estimate of average inflation expected over the next five years implied in the bond market, from the one year interest rate expected in five-year’s time, we get an after inflation expected return that year 5 of about 6%. This measure of inflation expected is now very close to actual inflation. As are the inflation expectations surveyed and reported by the Reserve Bank and forecast by them. They will all have declined further since the beginning of the year given the global pressures on inflation and the likely reluctance of SA households and firms to spend more over the next few years.

It is very difficult to imagine that the SA economy will be strong enough, or the Reserve Bank aggressive enough, over the next few years, to tolerate real interest rates of the order implied by the yield curve and the spread between nominal and real yields now available in the bond market. Therefore many borrowers, especially the SA government, is surely likely to take the risk that short term interest will not rise nearly as rapidly as implied by the current slope of the yield curve. After all short-term rates are directly controlled by the Reserve Bank itself.

Borrowing long can be avoided and the growing SA government debt can much better be funded short rather than long, and by rolling over short term debt for as long, provided the level of long-term rates remains where they are. Drawing further on the government deposits at the Reserve Bank is a further low interest cost option. The Reserve Bank can also provide the banks with enough extra cash, on favourable enough terms, to have them support the growing market in short-term debt. Any reduced supply of longer-term paper will help take pressure off longer term yields.

For the government to elect to borrow long rather than short in current circumstances would surely now seem the wrong, very expensive option. The current state of the bond market could be argued to be something of an aberration in a world of global bond markets that have been monetized to an extraordinary degree. In the longer run the task for the SA government is to prove to the world that it can manage its debt in a sensible way. This means convincing potential lenders that it can bring government spending closely in line with its ability to raise tax revenues. This will help to bring down the long-term cost of raising RSA debt. In the short term, until the crisis is over, and the economy normalizes, what is called for from the government and its Reserve Bank, is the ability to manage the unavoidably larger national debt and short-term interest rates in a sensible way. If we call it good debt management rather than money creation- that it will be to some degree- then so describe it that way