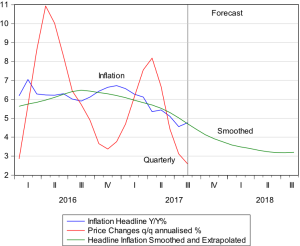

Inflation in SA rose to 4.8in August- up from 4.6% in July 2017. However in August 2017 prices were largely unchanged, rising by a mere one tenth of one per cent in the month. The statistical anomaly is that a year ago Consumer Prices had actually fallen by about the same 0.1 per cent. And so a monthly increase in August this year of 0.1% was enough to raise the year in year increase in Consumer Prices by 0.2%.

Of further and greater importanc% e is that the Consumer Price Index has been largely stable since April 2017. In April prices increased by 0.1%, in May by a still minimal 0.3%, in June by 0.2% and in July by 0.3%. Helped by a consistently stronger rand compared to a year before, and stable food prices following the drought of last year, the direction of inflation has been decidedly lower. Thus as we show below the increase in prices, measured over consecutive three month periods, has declined sharply. Were such trends to continue headline inflation would fall to three per cent. A time series forecast indicates a much lower rate of inflation next year of about 3%.

The Reserve Bank forecasting model of inflation, upon which it will determine its interest rate settings, is not a time series extrapolation of recent trends. It will have the trade weighted rand and food prices as amongst its more inputs. Chris Holdsworth of Investec Securities runs a simulation of the Reserve Bank model that suggest that the forecast rate of inflation for Q1 2018 will have declined marginally and would imply a further reduction in interest rates .[1] He remarks as follows

- Since the last MPC meeting CPI inflation has dropped from 5.1% in June to 4.6% in July. The MPC’s previous forecast was for CPI inflation to average 4.8% for Q3. The slightly lower than expected print should marginally lower the MPC’s estimate of the inflation trajectory.

- PPI has dropped from 4.8% in May to 3.7% in July. The fall in PPI inflation should further lower the inflation trajectory.

- We don’t expect the MPC to make meaningful adjustments to its ZAR and oil price assumptions.

- Subsequent to the last MPC meeting SA GDP growth for Q2 has come out at +2.5%, up from -0.6% in Q1. Given our understanding of the MPC’s macro-economic model, that should imply a small upward revision to the MPC’s growth assumption for the year (currently 0.5%). This should see a reduction in the expected output gap and an associated increase in the inflation trajectory but we expect the effect to be minimal.

- The net result is that we expect a minor reduction to the SARB’s inflation trajectory over the medium term. We expect that the SARB will forecast inflation to reach 4.4% in Q1 next year.

A further reduction of 25 basis points in the repo rate therefore seems likely. Especially given the continued absence of any demand side pressures on prices. And so given to the near recession state of the economy. And were the stability of the rand to be maintained and a normal harvest delivered in 2018 the current underlying trends in consumer prices in SA would be sustained and lead to further reductions in headline inflation and forecasts of it and be accompanied by still short term interest rates. Rates that could fall further and until very welcome strength in spending by households and firms becomes manifest. The conditions for a normal cyclical recovery are falling into place. One can only hope that political developments do not reverse the direction of the rand and the SA risks spreads that have also been receding. Presumably on the belief that better government is in prospect.

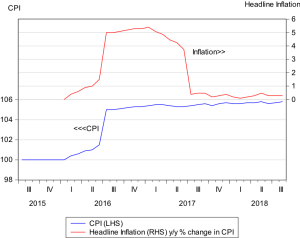

It is perhaps worth making an observation about inflation – measured as a year on year increase in prices and – and the advantage in identifying underlying trends in prices within a twelve month period that may be much lower. And portend lower headline inflation to come. The problem for inflation watches and commentators on it – and drawing implications for interest rates- is that 12 months is a long time in economic life. That much of importance can happen to prices or any monthly series within a year that makes year on year comparisons out of date. This is illustrated in a hypothetical example shown below. We show a case of a sharp increase in the price index after a period of stability and low inflation and how this may lead to more and then sharply lower inflation after twelve months.

In the figure below we show a sharp 5% increase in the CPI in early 2016. An increase in the VAT rate or a collapse in the ZAR might be responsible for such a sharp increase. Thereafter prices are assumed to stabilise for an extended period of time. Perhaps this is because he exchange rate recovers somewhat and the VAT and other tax rates do not increase further. As we show inflation – measured as a year on year increase in prices – initially increases sharply to about 6% p.a and remains at these elevated levels for a full twelve months- where after it collapses back to about zero inflation.

Thus the impact on inflation of an inflation shock will be very temporary provided the underlying trend in prices is a very stable one. Presumably also inflationary expectations as well as models of inflation are fully capable of see through a temporary price shock. One would hope that monetary policy settings can also see beyond temporary year on year changes in prices. As we hope the SA Reserve Bank is looking ahead rather than behind and will take the opportunity to help stimulate a recovery in spending that is desperately needed.

|

||