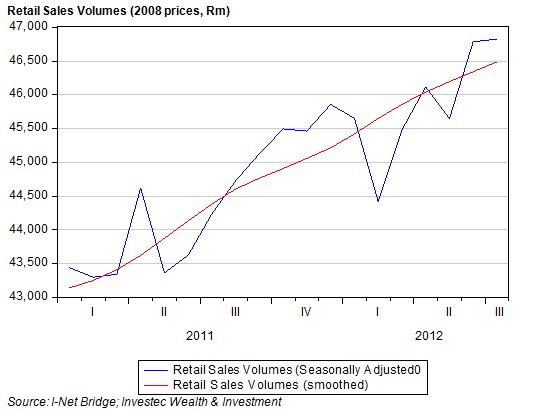

There would appear to be some disappointment with the retail sales numbers for July 2012, details of which were released on Wednesday. We would argue by contrast that sales volumes in July confirmed a strongly upward trend in sales that began in May 2012, gathered strong momentum in June and was well sustained in July 2012. Retailers and their shareholders have every reason to be satisfied with this sustained revival in sales volumes.

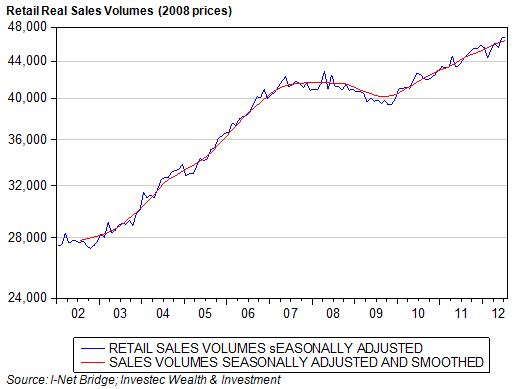

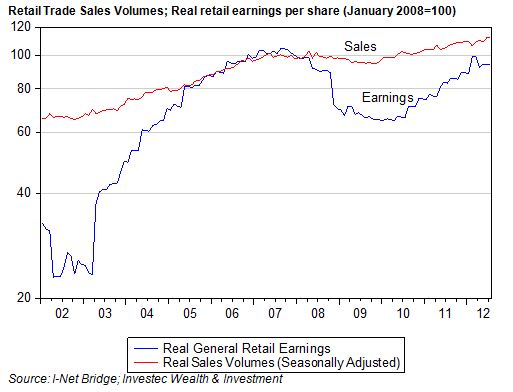

The highly satisfactory longer term and shorter term trends in recent sales volumes are shown below. It will be seen that retail volumes have recovered significantly from their recent recession which hit a trough in 2009. In constant 2008 retail prices sales volumes in July 2012 (at record levels as may be seen) were some 17.3% above their lows of October 2009.

The real (CPI) adjusted earnings per share of the General Retailers Index of the JSE has clearly benefitted from the strength in sales. Real Retail index earnings per share have responded even more strongly than sales volumes, having risen nearly 40% from their April 2010 lows – though they have still to exceed pre-recession real levels of earnings.

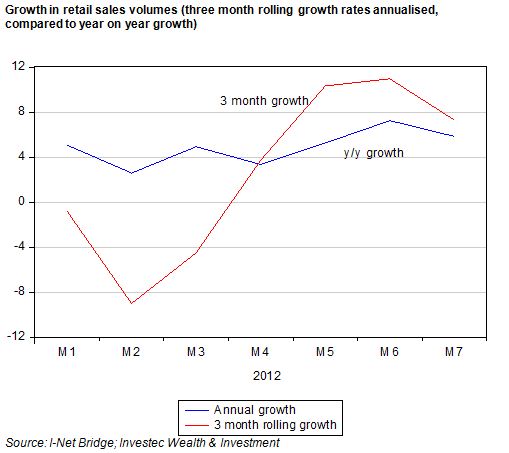

These differences in interpretation of the state of the retail trade sector owe everything to the period of time over which growth is measured. The year on year growth rates, comparing levels this month to the same month 12 months before, are highly smoothed estimates. They can easily miss much of what has transpired through the year. A year can be a very long time in economics as well as politics. The value in looking at retail sales trends over a shorter period than a year is particularly apposite this year.

Retail sales volumes grew strongly in the final quarter of 2011; they were especially buoyant in December 2012 when seasonally adjusted – as they have to be given the strong seasonal influence on sales. This is especially important in the Southern Hemisphere when Christmas spending is combined with summer holiday spending. The seasonal adjustment factor is 1.36 for December and 0.96 for August. That is to say: December sales can be expected to be about 36% stronger than the average month and July sales about 3.3% weaker than the average month.

The growth in retail sales volumes of 4.2% year on year was reported by I-Net Bridge as being well below market consensus that expected a 7.2% rise in sales volumes. The sales volumes reported were based on a new sample survey of the retail sector, making consensus forecasts perhaps less relevant than they usually are.

Based on these new sample sales volumes, seasonally adjusted as they have to be to make good sense of them, the level of real sales volumes in July were only up a marginal 0.1% on June 2012. However June 2012 was a very good month for retail sales volumes. Moreover estimates of sales in June 2012, applying the new sample estimates, were also revised upwards providing a higher base from which growth in July was estimated.

These trends are well captured by annual growth measured on a three month rolling basis. After rising sharply in late 2011, the rolling three month growth in the seasonally adjusted sales volumes fell off sharply in the first quarter of this year and then recovered strongly. The current year on year growth rate in the seasonally adjusted volumes is a robust 5.9% (not 4.2% as per the unadjusted numbers) while the rolling three month growth rates, having risen to over 10% in May and June, have receded to a 7.3% annual pace.

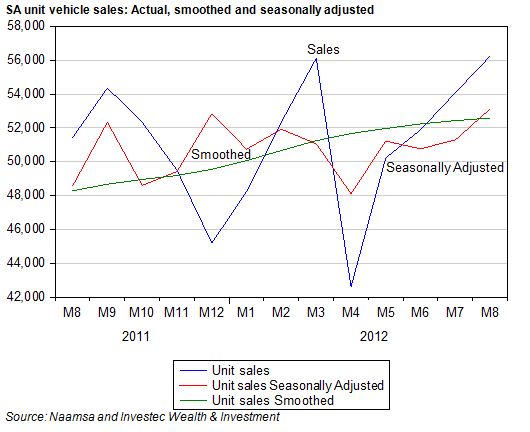

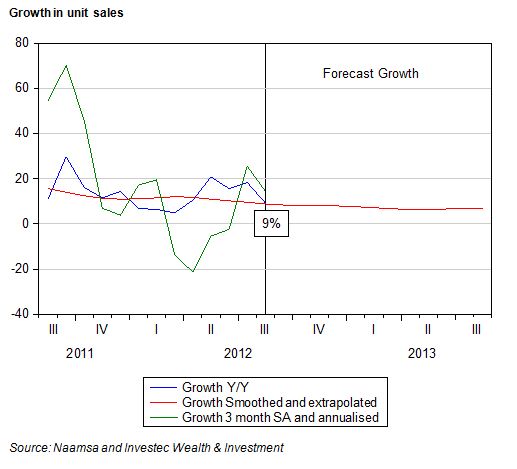

This momentum in retail sales volumes in July is highly consistent with other economic indicators we have reported upon. Retail sales volumes, like unit vehicle sales and the value of notes in circulation, when seasonally adjusted, were no higher in May 2012 than they had been in December 2011. Retail sales volumes, vehicle sales and cash in circulation had similarly demonstrated very strong growth in late 2011,

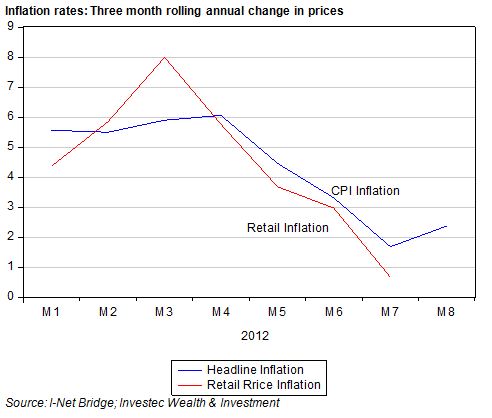

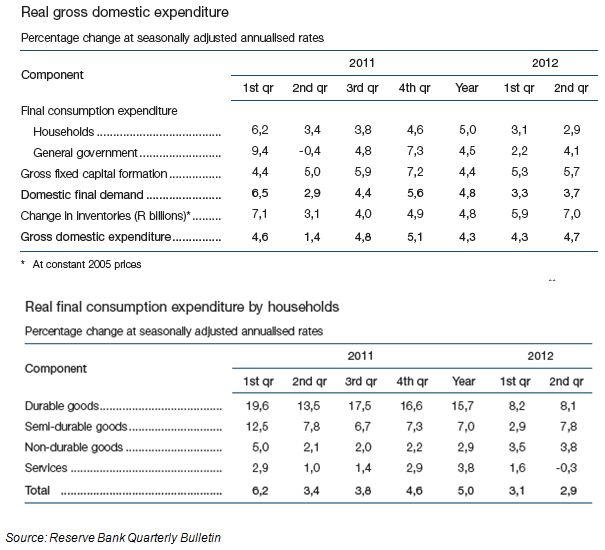

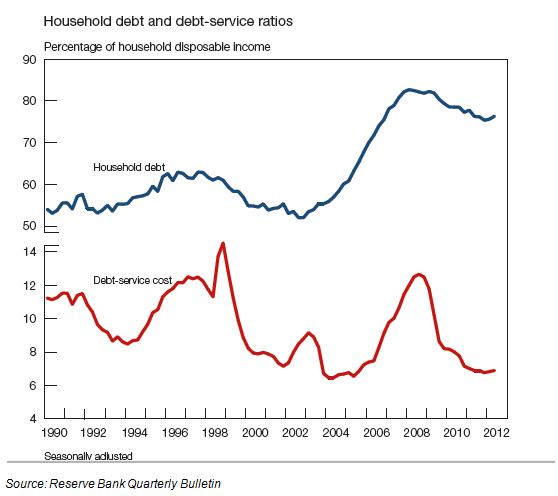

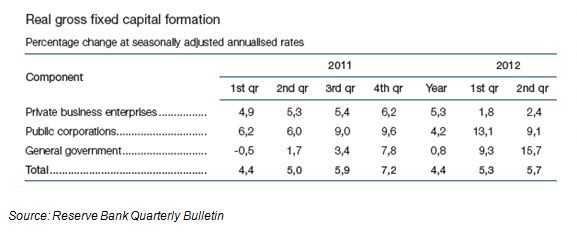

The economy therefore would seem to have a little more life in it than is usually recognised. Household consumption spending grew very slowly in the second quarter, at a less than 3% rate. It would appear that spending growth has picked up since then and perhaps a lot more so for the merchandise supplied by retailers and motor dealers. This is in contrast with the demand for services by households. Low rates of inflation have helped encourage demand for goods; while much faster inflation of the prices of services (as much as 10% per annum faster) has discouraged the demand for services.

The difference between year on year changes in the CPI (headline inflation) and more recent trends in consumer prices has also become vey significant recently. While year on year the CPI was up very marginally from 4.9% to 5%, recent trends in the CPI have been much more favourable. On a three month rolling basis CPI inflation slowed down to below 3% p.a in August, the result of a succession of very small monthly increases. The CPI increased by 0.24% in August 2012 from 0.325% in July, 0.24% in June and 0.08% in May 2012. Retail goods inflation, as represented by changes in the retail goods deflator, slowed down almost completely in the three months to July 2012, as we also show below.

A sense of inflation trending down (as per the rolling three months growth rates in the CPI) or trending up (as per the year on year growth rates) leads to implications for the inflation outlook and so perhaps to interest rate settings. That monthly increases in the CPI were very high in the early months of 2012 means that there is every chance of a sharp decline in the year on year inflation rates in early 2013. Monthly increases in the CPI in late 2011 were by contrast very subdued, meaning that the year on year headline rate of inflation is likely to rise in the months immediately ahead.

These month by month blips in the headline inflation rate should surely be ignored. It is the underlying trend that will be either friendly or unfriendly for the longer term trends in the CPI. And this trend will be dominated by the rate of exchange for the rand – over which interest rates and monetary policy have no predictable influence if again past performance is the guide.

The notion that year on year headline inflation should lead the direction of interest rates in SA – rather than the state of the domestic economy – is an idea that has fortunately lost credibility at the Reserve Bank if not yet in the media. Brian Kantor