We look at the regional and other factors at play in the failure of to employ more people and draw some conclusions about what can be done about it.

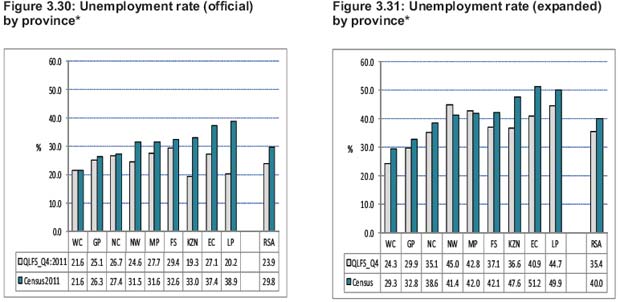

Unemployment as well as incomes varies significantly by Province.

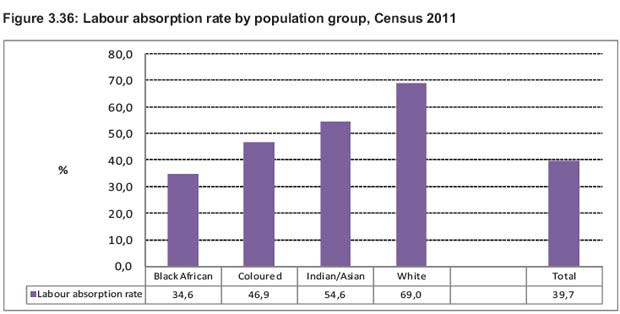

According to the 2011 Census a mere 39% of the adult population of SA is employed. The rate of absorption into the labour market varies from 70% for the white group to about 33% for households headed by black Africans (see below)

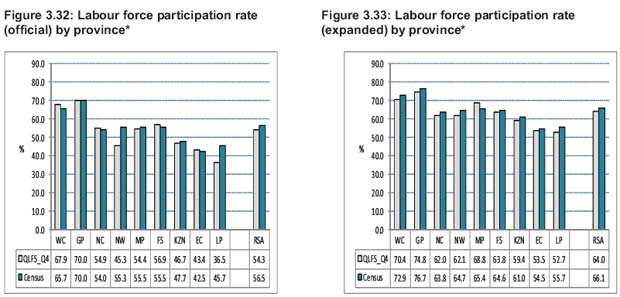

When those registered as unemployed by the census are added to those employed, the participation of the adult population in the labour market can be established. The average rate of participation of adults in the labour market is of the order of 55% of the adult population force, using the stricter definition of unemployed.

*Note The provincial order in the above two figures corresponds with the order used in the QLFS, and is therefore different from the geocode which is used in other publications.

Source: Census 2011

*Note The provincial order in the above two figures corresponds with the order used in the QLFS, and is therefore different from the geocode which is used in other publications.

Source: Census 2011

The census indicates not only significant income differences across the provinces, but also highly significant differences in the unemployment rate across the different provinces, as is shown above. The poorer the province, the higher the unemployment rate of that province and the lower the rate of participation of its adult population in the labour market. The unemployment rate ranges from about 20% in the Western Cape to nearly double 40% in Limpopo.

The participation rate in the labour force ranges from nearly 70% in Gauteng to barely 40% in the Eastern Cape. The divide between the provinces appears very much as an urban rural divide. It is the highly urbanised provinces, Gauteng and Western Cape, which deliver higher incomes and much faster growth in employment.

Population and employment has grown fastest in Gauteng and the Western Cape

The unemployment rate is lowest in the provinces to which people have migrated in significant numbers over the past 10 years: Gauteng, with net migration of over 1m people, and the Western Cape, which has absorbed over 300 000 extra people since the last census in 2001. The population of Gauteng, 12.27m in 2011, making it by far the most populous province, grew by 30% over the 10 years – twice the national average and that of the Western Cape (28%).

Clearly employment growth in the two fast growing provinces (given little change in the unemployment or labour force participation rates in Gauteng and Western Cape since 2001) has also been well above average too. The implications of these demographic and economic trends would seem to be obvious. If a greater number of South Africans are to be employed they are most likely to be employed in fast growing Gauteng and Western Cape. Or in other words, the rate of migration to Gauteng and Western Cape will have to accelerate further if the unemployment problem in SA is to be addressed in a meaningful way.

What it means to be employed, unemployed or not working and therefore not part of the labour force

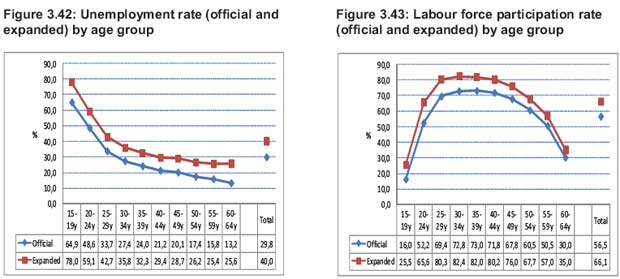

According to the census, of the SA working age population (16-65) of 33.2m, only 13.18m were employed – a “labour force absorption rate” of a mere 39.7%. The census counted 5.594m workers as unemployed, leading to an unemployment rate of 29.8%. The SA labour force is the sum of the employed (13.18) plus the unemployed (5.6m) or a labour force of 18.7m potential workers. The numbers of adults defined as “not economically active” by the census numbered 14.5m. Thus, the labour force participation rate in SA was but 55.6% of the adult population of 33.2m in 2011.

The Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) conducted regularly by Stats SA counted fewer officially unemployed in 2011, some 4.24m unemployed and so an unemployment rate of 23.9% – presumably because those conducting the QLFS applied a stricter interpretation of actively seeking work.

Those officially unemployed according to the Census would have responded affirmatively to the question in the census questionnaire (P25) “…that they had looked for any kind of job or tried to start a business in the four weeks before October 10th 2011”.

In other words you are only regarded as unemployed if you have recently actively sought work. You may not be working for a variety of reasons, including studying or having retired early or a full time home maker, or more simply because you prefer not to work. If you are neither working nor seeking employment you are understandably not counted as part of the labour force. By neither working nor seeking work your actions can have no influence on the numbers employed or employment benefits (wages and salaries) offered and accepted –hence you are not participating in the labour market.

The census asked a number of further questions as to why people were not seeking work. Among the possibilities considered included “no jobs available in area” , “ Lack of money to pay for transport to look for work” and“No transport available”. The census also asked a supplementary question “If a suitable job was available would you take up the job within 7 days”? A job to be regarded as suitable must include a sense of attractive enough pay as well as within easy reach of the household. Thus it is surely unlikely that any potential worker not working or seeking work would respond anything but positively to such a hypothetical, probably highly unrealistic, offer of a suitable job at an attractive wage nearby. If an attractive employment opportunity were on offer many of the currently not working in rural SA would happily take it up. But the prospect of finding such work in the rural areas is very poor. Answering yes to such a purely hypothetical question would therefore not make you a member of the labour force in the sense considered earlier, in the sense of your actions or intentions having any influence on the supply of demand for labour or rates of remuneration.

Including those who would work, if only an attractive enough opportunity were offered them, greatly increases the numbers of the unemployed. It would include as unemployed all those whose experiences seeking work and not finding it would have discouraged them from seeking work and so led them to withdraw from the labour force and to stop looking for work that is practically not available. However should these discouraged workers be included in the ranks of the unemployed, a higher expanded unemployment rate would follow. Perhaps the census unwittingly included many more discouraged workers as unemployed compared to the QLFS.

Why those not working – especially in rural SA – should be regarded as not working and therefore as not part of the labour force or unemployed

For many potential workers, particularly in the rural areas of SA, the knowledge that there is no realistic chance of a job in the area does not make them unemployed and therefore they are not part of the labour force.

Workers in rural areas might be willing (even if reluctantly) to accept employment at lower wages if given the opportunity to do so within easy reach. The clothing workers in Newcastle, KwaZulu-Natal, provide such a case study. The reasons why there are in fact so very few jobs offered in the rural area may have a great deal to do with the regulation of wage rates (minimum wages and nationwide wage agreements for example).

These regulations discourage potential employers, using labour intensive methods, from offering employment at lower wages that workers outside the major urban areas might well be willing to accept, as an alternative to not working. It is perhaps only lower wages that can make rurally based enterprises competitive with those employers operating in the urban areas. In the major centres, well established firms are able to provide better employment benefits, because of all the other advantages an urban area offers to business, for example, being close to customers or transport nodes and having easy access to essential services and skills. These advantages are not typically available in more remote regions and the opportunity to pay lower wages may be the only reason for operating in a more rural location.

The realistic alternative for many potential workers now not working in the rural areas is to seek work in the cities where opportunities to seek and find work are a realisitic alternative. When typically younger workers migrate to the urban areas to seek work they qualify as part of the potential labour force – and hopefully they will be only temporarily unemployed. Their decisions to migrate to the cities will have an impact on the labour market in the urban areas.

It is not accidental that labour force participation rates in SA (those in work and looking for work) as a percentage of the adult population peak at between 70% and 80% for the cohorts between the ages of 25 and 45. (see below)

But potential workers, by electing not to migrate to the cities of opportunity for whatever reasons, are unlikely to ever be able to find work in the rural areas in significant numbers. But it makes little economic sense to describe such non-workers as unemployed. They are however part of a potential labour force that, with very different economic policies, might become a much more productive part of the labour force.

Regional policies to encourage employment and participation in the labour force

Such policies might usefully include better, well targeted Budget support for those urban regions of the country that have proved able to create additional employment. The right policies might include better funded housing, schools, vocational training and hospitals and the transport systems that could make these regions still more attractive to potential migrants and potential employers.

Poverty relief in the form of cash grants provided on a means tested basis to support children, the aged or the disabled can and has had the unintended consequence of discouraging entry into the labour market, especially from the rural areas of SA. As economists put it, such support for poor families raises the reservation wage of labour: it raises the wage that makes it worthwhile to accept or even seek work. Such work, at wages attractively higher than the reservation wage, may simply not be available in significant volumes outside of the urban areas.

It should be understood that for the unskilled the only work available might be physically onerous work at relatively low wages. But the incentive to work or seek work does depend on the improvements in the household’s standard of living that may be realised by some family members accepting work (or by not seeking or accepting work by subsisting on the welfare system) or the family relying on some mixture of work and welfare.

The fact that the participation and employment rates in the labour force are so much higher for the average white than the average black SA resident has everything to do with these economic incentives. The white South Africans participate much more fully in the labour force because they can earn much more on average than they could expect from welfare.

Conclusion: the path to faster growth in the labour force

The best form of poverty relief in the long run is the creation of employment opportunities and of the skills that qualify workers for higher earnings. The best prospects for employment and income growth in SA are in those regions that have performed so much better in attracting and employing labour. Improving the economic performance of the provinces with competitive advantages should be a clear objective of economic policy. In this way the successful regions can better facilitate the creation of higher incomes and employment over time. Allowing for more flexibility in wage determinations across a diverse geography should be another.