What permanent shape will the global economy take after the lock downs are fully relieved? How fast can the global economy grow when something like normality resumes? There are those who argue that the major economies have entered an extended period of economic stagnation. Some even argue that demand will have difficulty in keeping up with minimal extra supplies of goods services and labour. That monetary policy has shot its bolt because interest rates cannot go much below zero.

We should dismiss such underconsumption theories. Monetary stimulus comes not only from lower interest rates but also occurs directly as excess supplies of money are converted into demands for other goods or services and for other assets. Higher asset prices and greater wealth also have positive effects on spending. There is no technical limit to the amount of money central banks can create to stimulate more spending. The only limit is their own judgment as to how much extra is necessary to the purpose of getting an economy up and running again.

Stagnation will be for a want of willingness to supply goods services and labour. If demand remains weak we should expect ever more injections of central bank cash until demand increases enough to make inflation rather than growth the problem for central banks. This is unlikely any time soon and global interest rates will remain low until then. Such policies can be reversed when the time is right to do so.

These low interest rates encourage a flow of capital to those parts of the world where real interest rates are much higher. As in South Africa where the market still rules the determination of long-term interest rates given the clear unwillingness of the SA Reserve Bank to monetize government debt on any significant scale. The SA government has to offer nearly 10% for ten-year money. Adjusted for expected inflation of around 5% this provides a very attractive expected real return of around 5% per annum over the next ten years.

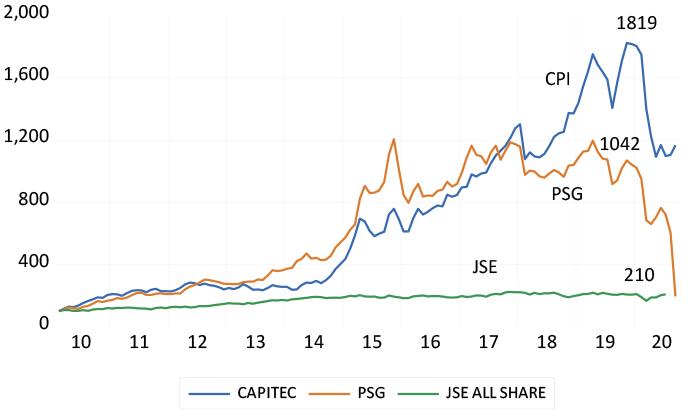

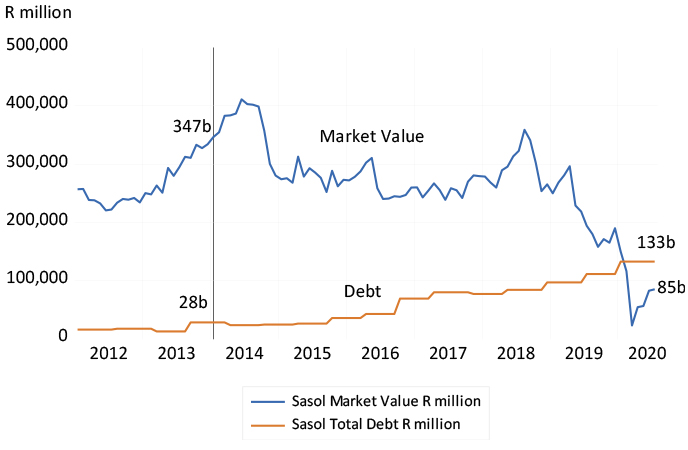

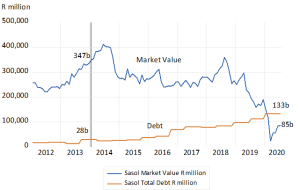

The average private firm contemplating investing in plant and equipment in SA would have to add a risk premium of another five per cent to establish the returns required to justify such an investment. These expected returns would therefore have to be of the order of an expected 10% p.a. after inflation. A requirement that is prohibitively high and explains in large measure the lack of capital expenditure in SA. And reinforces the prospect of a permanently stagnant economy. It also explains the depressed value of SA facing companies on the JSE regarded as without good prospects for growth. For faster growth in capex, interest rates have to come down or, less happily, inflation must go up to reduce required returns on capex.

Improving our growth prospects requires a steely economic realism in response to current very difficult circumstances. It necessitates more central bank intervention to lower long-term interest rates and much more reliance on short term borrowing that will be much less expensive for taxpayers. It calls for still lower interest rates at the short end. It calls for money creation and debt management of the kind practiced almost everywhere else as a temporary, post lock-down stimulus to more spending and growth- but alas not here.

The blow out in the borrowing requirement of the government –because revenue has collapsed with incomes – is a best regarded as unavoidable. Realism means no increases in tax rates on expenditure or incomes. Doing so would further slow-down the economy and revenue collections with it. Higher expenditure taxes and charges would also raise headline inflation, depress spending on other goods and services and raise demands from public sector unions for better pay. These now pressing demands for improved employment benefits for comparatively well paid and protected public sector employees must be strongly resisted. This will help demonstrate that the SA government can spend within its capacity to raise revenue over the longer term. The debt trap is avoidable.

It calls for policy responses that would best serve the economy now in crisis and act as a bridge to permanently sound policies of a market friendly nature. So providing a signal of improving prospects that would justify significant inflows of capital to lower interest rates and required returns. That in turn would lead to much higher levels of capital expenditure necessary for permanently faster growth.