Interview with Brian Kantor on CliffCentral.com, discussing the impact of the Covid-19 lockdown: http://cliffcentral.com/gcs/gareths-guests/professor-brian-kantor/

Month: May 2020

Is it time for money creation on a significant scale in SA?

Funding extra government spending via loans from the central bank, can be a helpful form of government finance when spending is growing rapidly to meet an emergency.

Today is a time of epidemiologists, central bankers and yes, of schemers too. We will discover in due course whose reputations will have survived the economic crisis better intact.1

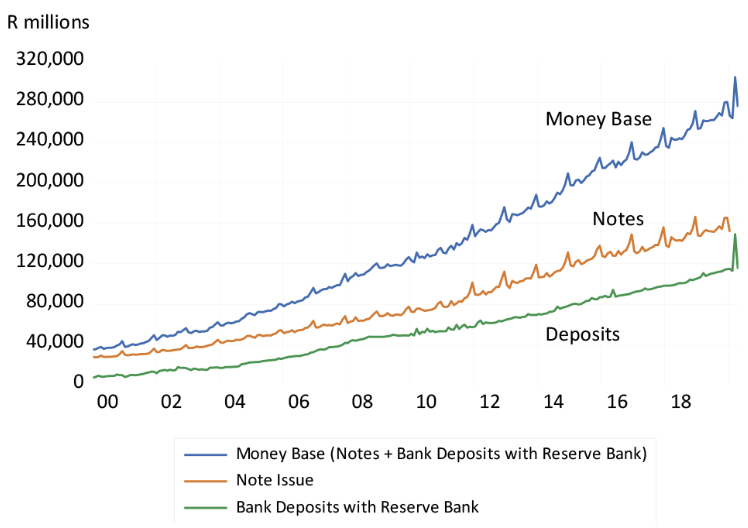

Central banks have an essential duty to create extra money for a growing economy. They do so on a consistent basis in normal times. Their extra money comes in two forms: as notes and coins and in the deposits private banks keep with their central banks.

The SA Reserve Bank has not failed in its duty to supply more cash to the economy over the past 20 years. For much of the period it might have supplied too much cash. More recently, it can be criticised for supplying too little for the health of the economy as we shall demonstrate.

The sum of the notes and the deposits issued by the SA Reserve Bank (the money base) grew by 7.9 times between 2000 and April 2020, from R35bn to R275bn at an average compound rate of 8.7% a year over 20 years.

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment

1 With apologies to Edmund Burke, responding to the excesses of the French Revolution: “Today is a time of sophists, economists and schemers.” – Reflections on the French Revolution

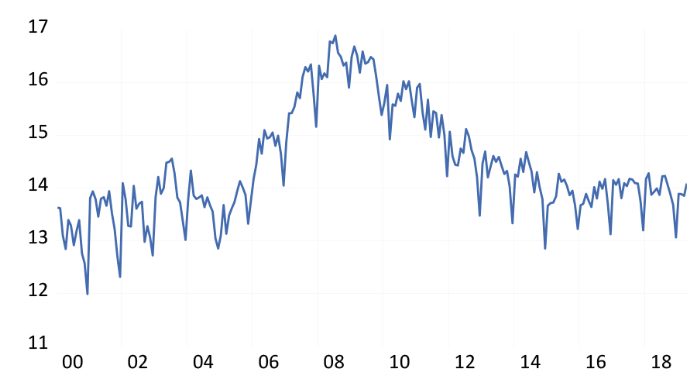

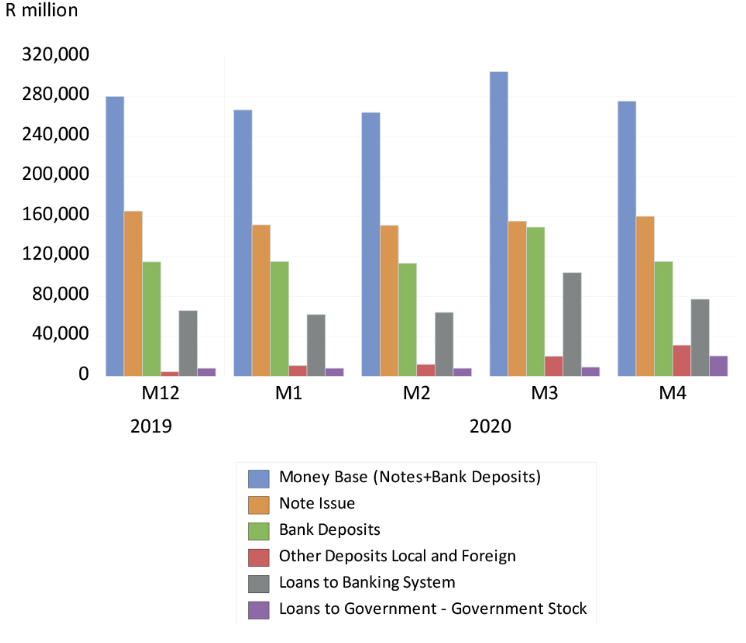

Figure 2: Calculating the money multiplier – the ratio of broad money (M3) to central bank money (money base) 2000 to 2019

The Reserve Bank balance sheet has been updated to April 2020. The money base (notes plus bank deposits) as at the end of April 2020 was in fact R5bn smaller than it was at 2019 year-end, despite the crisis. The money base fell by R29.4bn between March and April 2020, even though the note issue itself rose by R4.82bn in April, surely in response to crisis fears. The deposits of the banks however fell more sharply, from R103.4bn in March to R77.34bn by April.

The Reserve Bank’s portfolio of government stock, a small part of its asset portfolio, grew from R8.1bn at year-end to R20.6bn in April. This may be compared to loans made by the Reserve Bank for the banking system. They grew from R65.8bn at year-end to R103.9bn by March, but then (surprisingly in the crisis circumstances) fell back to R77.34bn by April month-end.

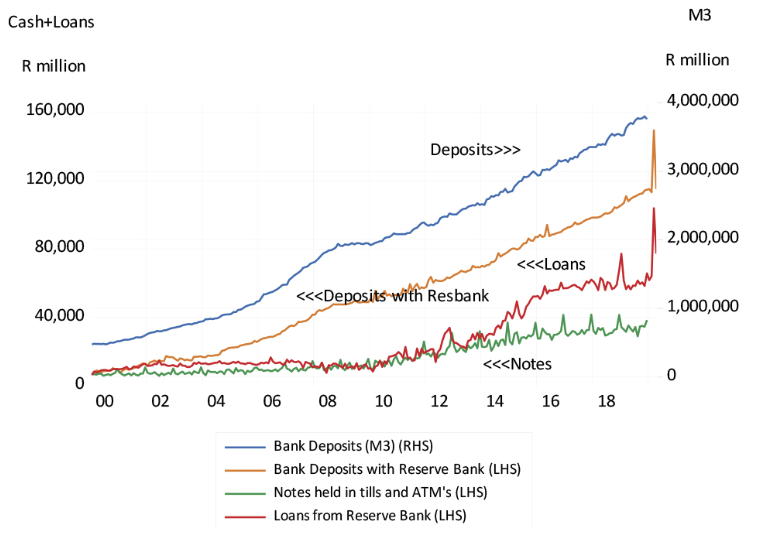

If the Reserve Bank were to embark on meaningful money supply growth loans to the banking system, its holdings of government stock would have to increase meaningfully. An increase in Reserve Bank lending to the banking system on favourable terms would allow the banks to support extra issues of short-term Teasury obligations at hopefully much lower rates of interest (see figures below for details of the balance sheets of SA banks since 2000 and of the Reserve Bank balance sheet this year).

Figure 3: SA banks deposit liabilities (M3), and uses and sources of cash

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment

Figure 4: The Reserve Bank balance sheet (selected items) to April 2020

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment

There is always a temptation for a government to borrow money from its central bank to fund its expenditure by issuing money. Almost zero cost money may be issued as an alternative to raising taxes or paying interest on the debt it raises to fund its expenditure. It is a temptation that is widely (but not always) resisted.

How much money should be created as a service to an economy and its banks that manage the payments system? The answer in very general terms is for a central bank to supply not too much and not too little cash for the economy. Not too much – that is not to supply more than the households, businesses and banks would willingly hold as a reserve of spending power. But to supply enough extra cash to satisfy demands that would grow normally in line with real economic activity.

It is not the supply of money and of associated bank and other credit that represents inflationary dangers or the danger of asset price bubbles that must all end badly for an economy. It is the excess of the supply of money – over the willingness to hold the extra money supplied – that is to be avoided if inflation is to be controlled.

Also to be avoided is to supply too little money. If the supply of extra money is constrained, economic actors would be inclined to cash in assets or save more to build up a cash reserve. This too would not be good for an economy.

The task central banks set themselves is to smooth the business, money and credit cycles by adjusting the cost of the money they supply to the economic system. They raise the repo or discount rates they charge the banks who borrow from them, when the economy and the supply of bank credit appears to be accelerating too rapidly. They will also lower the cost of their money, reduce the repo or discount rates, to encourage the banks to extend more credit to avoid or overcome a recession. However this fine balance of additional supplies of and demands for money is seldom achieved. The business cycle has not been eliminated by modern monetary policy.

The business cycle – extended periods of above and then below potential real growth – can be mostly linked to phases of more rapid and then much slower growth in money supply and bank credit. Inflation, for which a central bank usually has a target range, will tend to follow the direction of the business cycle.

The times when the price level takes a course independently of the direction of the business cycle calls for particularly sensitive attention by the monetary authorities. Raising interest rates in response to a supply side shock to the economy that results in temporarily higher prices (for example following a shock to the oil price, food supplies or to the exchange rate) may well prove to be pro- rather than counter-cyclical. It may slow the economy down further than it might otherwise have done.

These norms and objectives for monetary policy do not apply in the extremes of a crisis, when sudden demands for extra cash threaten the banking financial and payments system. The solution for a crisis is for a central bank to supply as much extra cash as is necessary to prevent ordinarily sound businesses and financial institutions from going under and dragging the economy down with them.

Shutting down an economy to fight a pandemic is a new challenge for monetary policy. It also calls for a rapid increase in the supply of central bank money and sharply lower interest rates where there is room to lower them.

Funding extra government spending via loans from the central bank, or funded by a banking system well supported with loans from the central bank, is a helpful form of government finance when spending is growing rapidly to meet an emergency, and correctly so. Funding with money or near money avoids the long-term burden for taxpayers of funding extra debt issues at high interest rates in an unwilling capital market. And by adding extra money to the system, it makes a much-needed recovery of spending more likely when the economy comes out of lockdown.

The extra money cannot be inflationary until the economy and spending recovers. At that point, the growth in the supply of money and credit can be reduced or reversed in the usual way.

When an economy is forced to its knees, an emphasis on inflation targets makes little sense. SA urgently needs and deserves (proportionately) as much extra money as is being provided in the developed world. By contrast, the money base in the US has been increased by 40% this year with more money on the way.

South Africa should not be held to a different fiscal or monetary policy standard in a time of crisis.

The history of the Corona virus catastrophe will come to be written. The costs as well as the benefits of lock downs will be calculated as best they can. The benefits and costs of not locking down as in Sweden or Brazil, will provide useful comparisons.

The benefits will be measured in infections avoided and in lives saved. The future incomes of those spared to continue productive working lives will be measured as part of the economic benefits realised. As should all the collateral damage from other medical threats to survival not adequately dealt with because of the attention focused so heavily on the victims of Corona virus. On the positive side of the cost benefit equation, damage avoided from fewer fatalities and injuries on the roads or in the factories and mines will be part of the calculation. The costs of the lock down will be calculated, much less controversially as the value of incomes and output sacrificed in the lock downs.

The history lessons learnt may teach us about how best to cope with a future pandemic of inevitably uncertain cause, effects and consequences. And where the appropriate policy responses can never be obvious before the spread of the disease. The relationship between the economic costs and medical benefits of any policy responses to an epidemic deserve the most careful consideration. We are not at all sure they have been properly calibrated.

The case for governments building a large and yet very expensive reserve of medical capacity will have been greatly strengthened by what has happened. If only to allow for more time for leaders and their advisors to assess any new unknown pandemic threat to the community. A reserve that would allow more time for science to come to the rescue, before hospital facilities are overwhelmed, and so perhaps avoid the highly expensive lock downs.

What the lock downs will have cost their economies before economic life returns to something like normal will be measured with some degree of accuracy after the event. It will be the difference between all that might have been produced or earned (that is measured by gross domestic product (GDP) had economies not been shut down to a lesser or greater degree, and what has been produced and earned despite the lock downs.

It is possible to forecast potential GDP by extrapolating the underlying trend in outputs and incomes before the crisis. A more complicated econometric model could attempt the same forecasts. The difference between this potential GDP and the GDP delivered over the two or three years, post the crisis, will give us an accurate enough estimate of the costs of the lock down.

We have estimated a GDP loss ratio for SA under lock down. We have made a broad-brush estimate of how much of potential GDP will be produced each quarter in SA. It is assumed in Q1 2020 that SA GDP will run at 90% of its potential, then in Q2, when the knock down impact will be at its most severe, we judge that the GDP will then run at 75% of what have been delivered without the crisis. Thereafter each quarter, the loss of output ratio reduces by 5% per quarter. That is GDP will rise to 80% of potential GDP to be produced in Q3, 90% in Q4, 95% in Q1 2021 and then back to 100% in Q2 2021.

This would mean a V shaped recovery bringing the economy back to its potential by mid-2021. This might be an optimistic scenario. But even so the loss in GDP each quarter on these assumptions could amount to a large over R1 trillion by Q2 2021. Whatever the more precise measure of actual GDP over the next few years, there are undoubtedly very large opportunity costs in the form of sacrificed output and incomes that South Africans will be bearing.

It would be a loss equal to about 25% of GDP delivered in 2019. And may be compared with the extra R500b rand the government plans to spend or provided tax relief to assist an economic recovery. Though not all of this R500 billion spending or tax relief programme will represent extra spending by government that will have to funded one way or another. Some of it will be covered by re-allocating some of the previous budget. Is the government plan generous enough? Such a judgment would depend upon on the estimate of its economic costs and benefits -rather than a narrow view of its financial implications. It can be funded with extra money created for the purpose. It does not have to rely on issuing extra interest-bearing debt raised that would be a burden on future taxpayers.

The less reliant the government is on funding the spending with expensive debt, the better it will be for future taxpayers. The case for funding a temporary increase in government sending with a temporary increase in the money supply, as well as with the almost free money provided by the IMF and World Bank, is surely the right way to budget. There is nothing ever to stop a sovereign as for example SA with its own currency, issuing more money to pay for goods and services that none would refuse. Issuing non-interest bearing central bank money is not normally used as an alternative to taxes or genuine borrowing to fund government spending because if pushed to excess, beyond the willingness of those who receive money in exchange to hold that money, it leads to inflation. Prices would tend to rise when the surplus money held by economic agents, including banks, is exchanged for goods and services and financial securities of all kinds including bank overdrafts. But in current crisis circumstances, when demand for goods and services is so depressed higher inflation, runaway inflation, is a distant threat. And one that can be removed by taking money out of circulation when the state of the economy is strong enough.

The sacrifices of income and output will not be shared equally by all South Africans. Many will lose jobs that will be difficult to replace. Others will lose their jobs and the businesses that self- employed them. Some businesses will survive better than others in the new world of business after Corona virus. Many will see the value of the pensions and retirement plans, their hard earned savings, painfully reduced.

Businesses to survive will need a reserve of working capital to start up again. The banking system, with assistance from the government and its central bank, as is the intention, can help those with viable businesses, but without the means to start them up again without additional bank credit. It would only be fair for the government that has so damaged the value of these enterprises, to help the banks do so- by creating money for the banks to deploy in the form of extra bank credit. And overspending to mitigate the damage caused would be better than underspending- especially if the charge to future taxpayers can be limited by money creation. At times like these traditional parsimony is not called for.

Would it be unfair to point out that those in SA who are employed by the government at all levels, will lose neither incomes nor the pension benefits the SA taxpayer has guaranteed them on retirement. Their willingness to accept a wage and salary freeze to help our fiscus when the economy returns to normal might seem a proper form of reciprocation.

The extra spending or tax relief offered by governments in response to the lock down, might add not only to demand for goods and services over the next two years, but can also encourage more output of goods and services. This stimulus to the supply side of the economy, as it is allowed to revive, will reduce the net loss of income and output. If this is the case such extra expenditure can in a real sense pay for itself. More demand that leads to more supply avoids any opportunity costs, the trade-offs that normally apply when resources are fully employed.

The actual GDP numbers over the next two years will be closely watched and used to update our GDP loss ratio in order to gauge the shape of the recovery. It will hopefully be a V shaped recovery as we have estimated – it could be a less helpful more prolonged U shaped recovery, with an extended bottom to the U should the economy struggle to revive its spirits and confidence. The economic recovery might worse even take a double u (W) course. That is a brief recovery followed by a further decline and then only later a recovery.

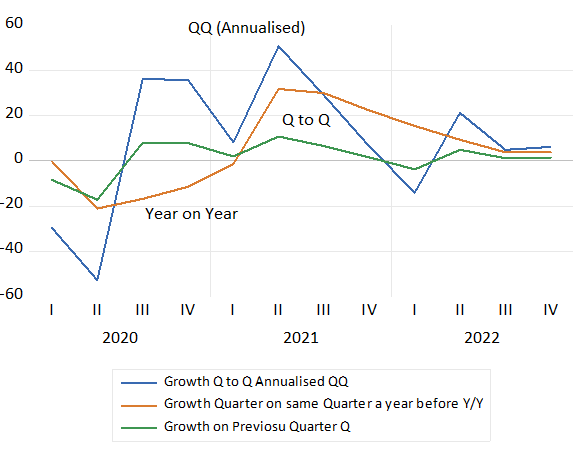

The economic growth rates as they unfold will not mean what they usually do. And therefore should be treated with great care over the next few years. GDP growth rates are most often presented as annual percentage growth from quarter to quarter, when the GDP has been adjusted for seasonal influences and converted to an annual equivalent That is growth from one quarter in seasonally adjusted GDP to the next quarter is then raised to the power of 4 to provide an annualized growth rate. This is the growth rate that attracts headlines.

Two consecutive negative growth rates measured this way are regarded as indicating a ‘technical recession’. The implication of this annual equivalent growth rate is that quarterly growth is expected to continue at that pace for the next year. Clearly under the influence of lock downs growth, so measured, is likely to become even more variable than it usually is.

This will be especially true of Q2 2020 when the impact of the lock down will be at its most severe, perhaps reducing growth in GDP to a truly shocking negative rate of minus 50% p.a or thereabouts.

Estimating growth on this quarter to quarter basis over the next few years will be a very poor guide to the underlying growth trends. Following our estimates of the loss ratio and GDP, as an example, would show a very sharp contraction in Q2 2020, to be followed by positive growth of 40% p.a. in Q3 and Q4, 10% in Q4 and then as much as 50% again in Q2 2021. The recession will seemingly have been avoided and the economy will soon be recording boom time growth rates. This would present a highly misleading account of what has been going on with the economy.

If GDP is compared to the same quarter a year before we will get a much smoother series of growth rates. It is likely to show negative growth throughout 2020, (down by as much as -20% p.a in Q2) with strongly positive growth of 30% resuming in Q2 2021 when measured off the highly depressed base of Q2 2020, when the lock down was at its most severe.

The better way to calculate the impact of the lock down in terms of growth rates would be to calculate the simple percentage change in GDP from quarter to quarter (not seasonally adjusted or annualized) as the impact of the lock down unfolds and gradually, we should hope, dissipates. The worst quarters measured this way will be Q2 and Q3 2020 after which quarter to quarter growth in percentage terms will become positive. See the figure below that turns our estimates of quarterly GDP in current prices over the next few years into the alternative measures of growth rates.

Estimated Quarterly Growth rates between 2020 and 2022 under alternative conventions.

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

The upshot is that growth rates will not be able to tell what has happened to an economy when subject to a severe supply side shock – that is temporary in nature. Measuring in absolute terms, in money of the day GDP sacrificed each quarter, as we have attempted to estimate, will tell the full tale of economic destruction under way after the events.

Monetary and fiscal policy should be fully engaged avoiding such disappointments. Much lower short-term interest rates, combined with a degree of money creation by the Reserve Bank, to assist the banks and other lenders to take up the extra short dated and low yielding Bills to be issued by the Treasury, will be necessary to the purpose. A mixture of significantly more government spending, hopefully well directed, and funded as cheaply as possible is called for to help revive the SA economy when it is given the opportunity to do so. Moreover there should be no sense of improper fiscal or monetary conduct acting this way.

It would be the right thing to do, and to do it openly without any sense of equivocation. As right a set of economic policy measures as they are being adopted in all the developed world whose economies are subject to similar proportionate losses of income and output. The developing world and South Africa does not deserve to be held to a different fiscal and monetary policy standard in circumstances like these. The time to resume sensible fiscal conservatism is when the economy is back to something like normal.