The market reaction to the release of US CPI data shows the extent to which the inflation dynamics have changed. Central banks should take note.

New York on 10 November was one of those days that will be fondly remembered by those with skin in the game, in the form of investments in the equity and fixed-income markets. This was the day that the key S&P 500 index added 5.54% to its value by the close of trading and the more IT-exposed Nasdaq added even more, 7.35%. These moves were the largest on any one day since the world came to realistic terms with the damage caused to their economies by the lockdowns of 2020.

Government bonds, which typically make up 40% of any conservatively managed portfolio, also became significantly more valuable as longer-term interest rates receded sharply. The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury fell from 4.14% to 3.82, on the same day, the largest such daily move since 2009 (the dollar value of bonds moves higher as yields decline). On the following day, as an illustration, the JSE All Share Index had gained 3.2% by 11h15, while the rand was up 2. 7% against the US dollar by mid-morning.

The source of all the good news was unusually obvious. US inflation for October reported that day was surprisingly low. Simply put, the (new) expectation of less inflation implied less aggressive Federal Reserve policies and lower-than-previously-expected short-term interest rates. Furthermore, the higher probability of the US avoiding recession added present value to stocks and bonds. The trend to lower inflation was further confirmed later, with similarly favourable market reactions: producer prices also surprised on the downside with prices rising by a month-on-month 0.2% in October, half the rate expected by the market.

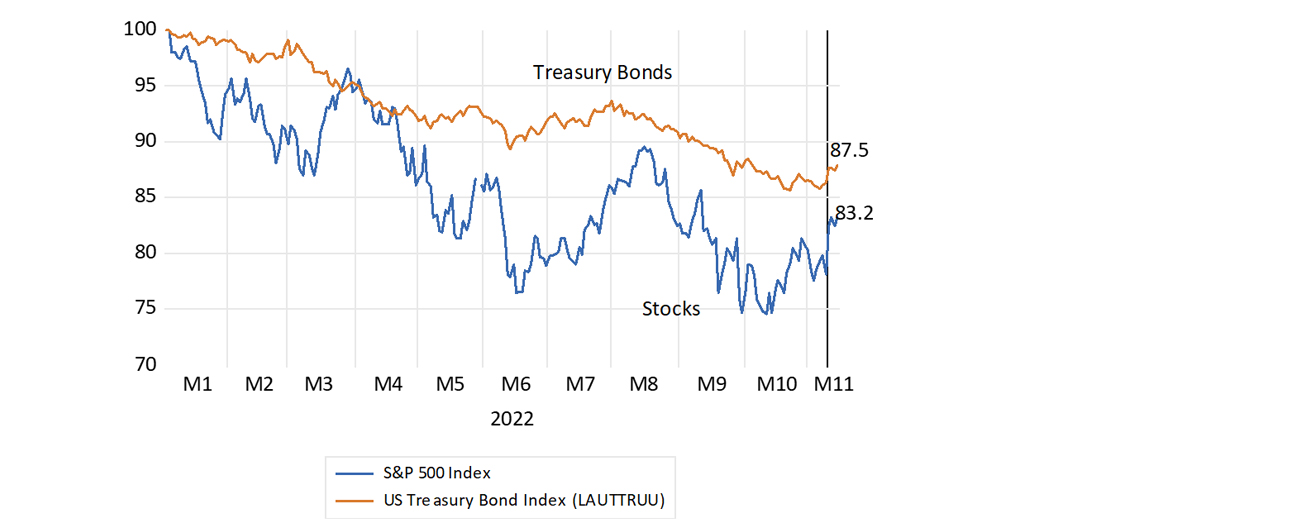

The Fed, having been so completely surprised by the surge in inflation in 2021, seems determined to march the US economy into recession to eliminate an inflation that they seemed unable to forecast with any degree of confidence. Monetary policy has become data-driven, guided by the view through the rear window. This has been accompanied by the fear that persistently high inflation could become a self-fulfilling tragedy for the US economy. The approach of the Fed seemed to be that, if a recession was the price to pay for avoiding permanently higher inflation, then recession it would have to be, much to the discomfort of the US share and bond markets. For the year to 15 November, the S&P 500 is down by 17% and the benchmark bond index is about 12% lower.

US stocks and bonds in 2022. (1 January 2022 = 100)

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment, 16/11/2022

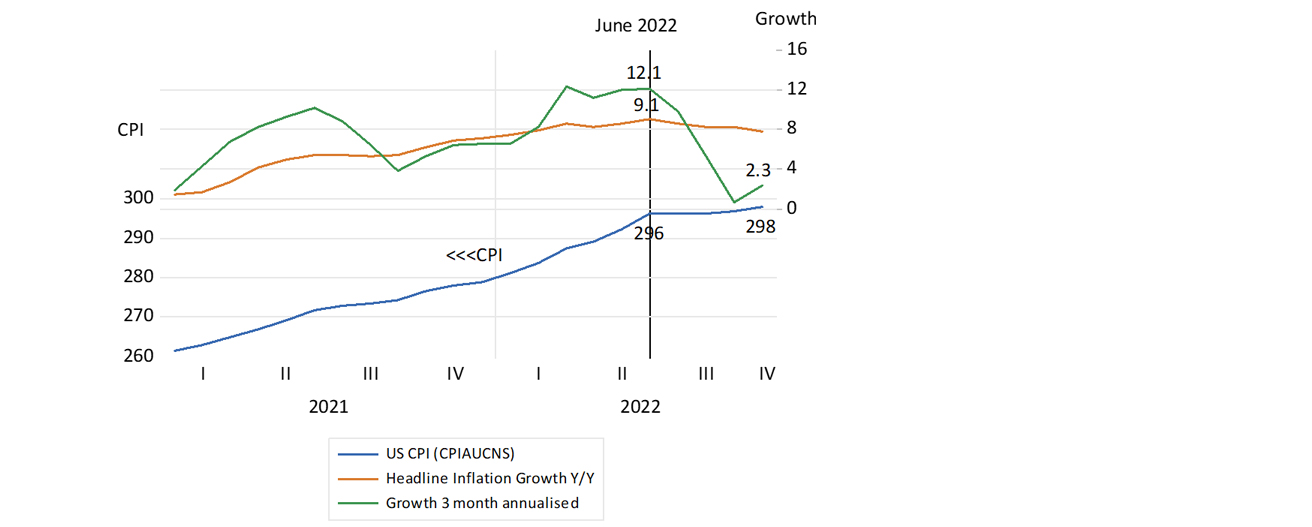

But should the Fed and the market have been so surprised? Surely not – if it had been closely following recent trends in inflation and spending by households and firms, then it would have appreciated why inflation had come to a screeching halt since its peak of 9.1% in June 2022. A year can be a very long time for an economy. The consumer price index (CPI), which was 9% higher in June 2022 than a year before, has flat-lined since June 2022. Consumer prices had stopped increasing in June and the increase over a rolling three-month period has slowed to a 2.3% annualised rate. If this trend in the CPI continues, then the inflation rate will still be a high 6.9% at year-end, but will then fall away sharply to less than 1% by June next year. US headline inflation is apparently on a path to zero.

Inflation in the US

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth & Investment, 16/11/2022

The Fed should be acting accordingly, by recognising that aggregate spending in the US by households and firms has already slowed down markedly and does not threaten higher prices to come. The weakness of aggregate demand is restraining price increases. Higher prices to date have largely absorbed the spending power that was so boosted by vastly extra money supply and Treasury handouts provided in response to the lockdowns. Higher prices have their demand and supply side causes, but higher prices have their negative effects on spending power. Higher prices absorb disposable incomes and spending power. Higher wages – even given full employment in the US – have not fully kept up with higher prices, further restraining spending.

Inflation cannot perpetuate itself unless it’s accompanied by continuous increases in the demand for goods, which has not been the case in the US or Europe. The notion, endorsed by the Fed and many other central bankers (including the SA Reserve Bank), that higher prices and wages can simply perpetuate themselves, is a false notion. Inflation expectations soon run aground on the rock of deficient demand and unintended excess inventories. This theory of self-perpetuating inflation will not pass the test of evidence. The Fed and the market should be following the weak trends in spending closely. Ever higher interest rates could in these circumstances turn minimal growth in spending into spending declines – truly the stuff of recessions.

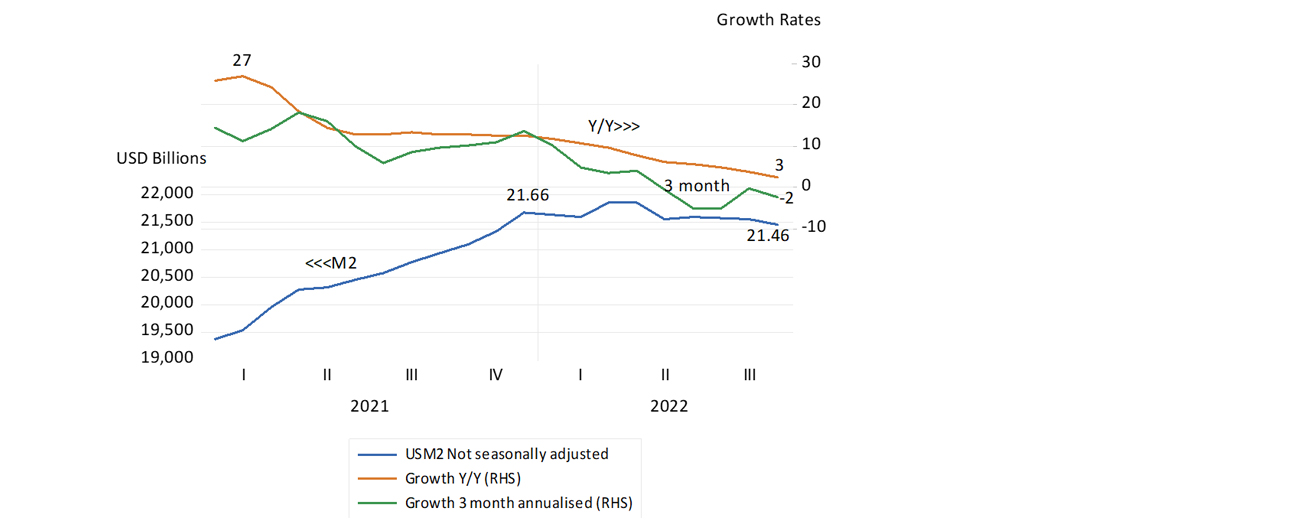

The Fed and the market would also be well advised to pay close attention to the trends in money supply growth. Inflation may be defined as a continuous increase in prices caused by an increase in the supply of money over the willingness to hold that extra money. All inflation is associated with excess supplies of money and the recent inflation in the US is no exception to this well-established rule.

A money supply explanation of the weakness of aggregate spending in the US also helps to explain why the demand for goods and services is growing so slowly. The important monetary facts are that money supply, broadly defined as M2 in the US, is now no larger than it was at the beginning of 2022. M2 amounted to US$21.62 trillion in January. By September, M2 had declined to US$21.46 trillion. The year-on-year growth in M2 that had peaked at an extraordinary 27% in early 2021 has slowed to a barely positive 3%, with the three-month growth rates now negative. Growth in commercial bank credit has also slowed down markedly. Year-on-year growth in bank credit was 7.6% in October 2022 while growth in bank credit provided has slowed to an annualised 1.6% over the past there months. The monetary, credit and price trends are pointing strongly to deflation rather than inflation by the end of next year. The market hopes that the Fed will recognise this in good enough time and avoid recession.

Money supply in the US (M2)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth & Investment, 16/11/2022