What inflation adds by way of higher prices, revenues or incomes, weaker exchange rates can be expected to reduce their value abroad. If the move in exchange rates was equal to the difference in inflation rates between SA and its foreign trading partners, the different fields on which we work or play across the globe would be a level one.

Clearly economic life does not work that way. Our rands almost always have bought us more at home than they do abroad – when exchanged at the prevailing exchange rates. The difference between what our rands can buy at home or abroad can be calculated as the difference between the market rate of exchange and its purchasing power equivalent, as determined by the differences in inflation rates.

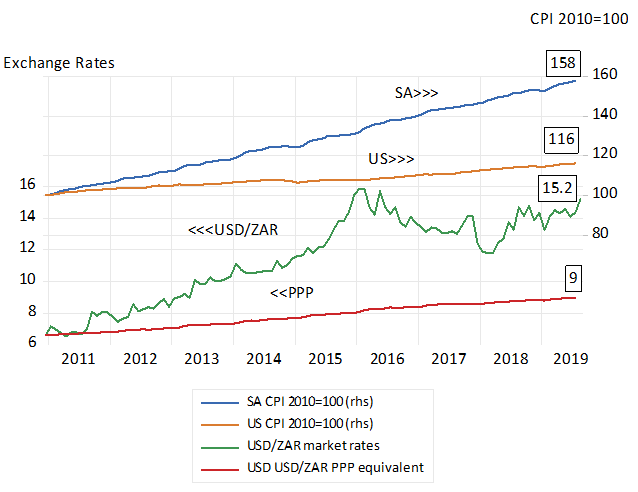

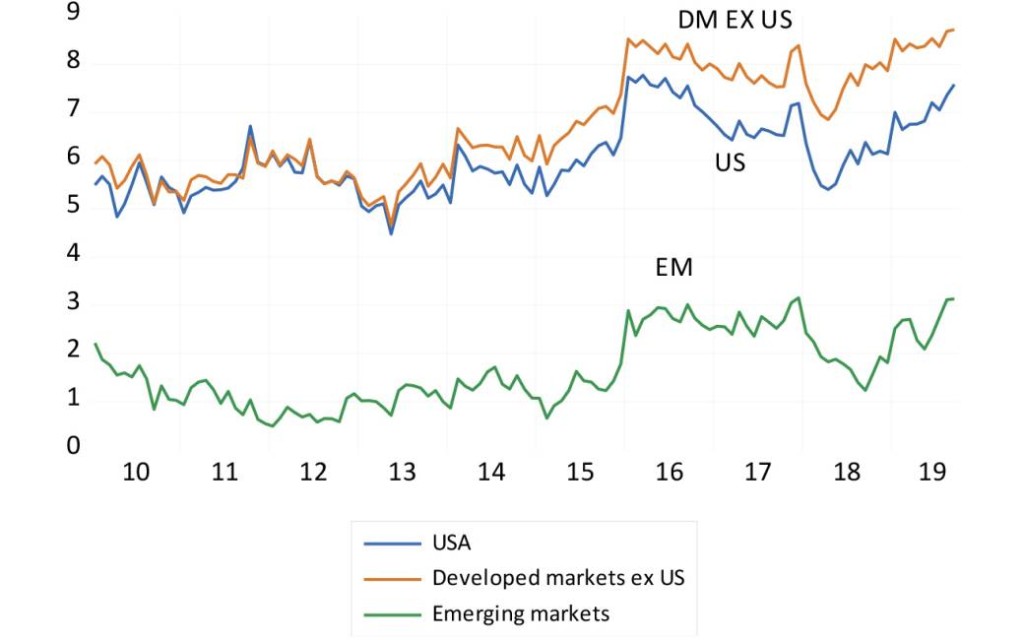

Since December 2010, when a US dollar cost R6.61, consumer prices in SA have increased on average by 58%. In the US average prices were up by a mere 16% over the same period. If the USD/ZAR had moved strictly in line with the changing ratio of consumer prices in the two economies (168/116 or 1.36) the dollar would have moved from 6.61 rands to 9 rands for a dollar in August 2019. (9/6.61 =136) A weaker exchange rate of 9 rands to the US dollar would have levelled the playing field. (see chart below)

2010 is a good starting point for such a calculation. The rand then was very close to its PPP equivalent were you to use 1995 as a starting point for the calculation. It was in 1995 that the rand became subject to largely unrestrained capital flows. Until then the (commercial) rand traded consistently close to its purchasing power value

The reality is that exchange rates are determined by forces that may have very little to do with actual price changes in the markets for goods and services. They move in response to global capital flows between economies that can dominate the flows of currency rather than to the flows of exports and imports that are price sensitive to a degree.

As a particular economy becomes more risky capital tends to flow away and exchange rates weaken and interest rates rise to balance supply and demand for the local currency. And if the shocks to the exchange rates are sustained, the inflation rate will respond as the prices paid for imported and exported goods in the local currency, increase or decrease- but with a time lag. This time lag determines the degree to which exchange rates diverge from PPP. The exchange rate leads and inflation follows – not the other way round – as theory might have had it. And convergence to purchasing power equivalent may take a long time.

Converting your SA wealth or incomes from rands into the equivalent purchasing power in the US at August month end would therefore have required the following adjustment. That is to reduce the 6.6 dollars received for R100 at market exchange rates by about 60%. This being the ratio 9/15.2 Having to pay only nine rand for a dollar would have been enough to net out the inflation impact. Rather than the R15.2 you actually had to give up for an extra dollar to spend in New York. (9/15.2*6.6 =3.9)

Thus any R100 of spending power in SA would have provided the equivalent of less than 4 dollars of roughly equivalent spending power in the US. Or in other words what would be regarded as a substantial fortune of R100m in SA would have provided a mere 4 million dollars of buying power in the US. Perhaps not enough to live well – or not nearly as well – as you could live in SA off your capital.

Consumer prices in SA and the USA and exchange rates (2010-2019)

Source; IMF World Economic Outlook Data Base. StatsSA, Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth and Investment

This purchasing power discount (((6.6-3.9))/6.6)*100= 40% at August month end) is a significant deterrent to the relocation of wealthy and skilled South Africans with only rands to support a life style in the developed world. Mobile younger South Africans, with a life of income earning and saving opportunities ahead of them, could undertake a similar calculation. That is multiply the prospective hard currency salaries they might be offered abroad, when measured in current exchange rates, by approximately 6/10’ths to account for their lesser purchasing power. Earning and saving rands at home (and perhaps investing abroad) might yield improved life-time consumption.

We should be relying more on better economic fundamentals than on an undervalued exchange rate to keep capital at home- especially our most valuable human capital. If South Africa would play the economic growth cards more effectively and reduce its risk premium it would retain and attract more capital on better terms. The nominal rand could then again approach its PPP value and the cost of borrowing rands (and dollars) would come down with less inflation expected. SA Incomes after inflation could grow at a much faster rate – encouraging immigration rather than emigration of capital and skills.