The Budget statement and speech on Wednesday badly disappointed the market in the rand and in RSA bonds. Since the Budget statement, the rand has lost about 3.3% of its US dollar value and was nearly 4% weaker against other emerging market exchange rates. This indicates that rand weakness and additional SA specific risks are at work.

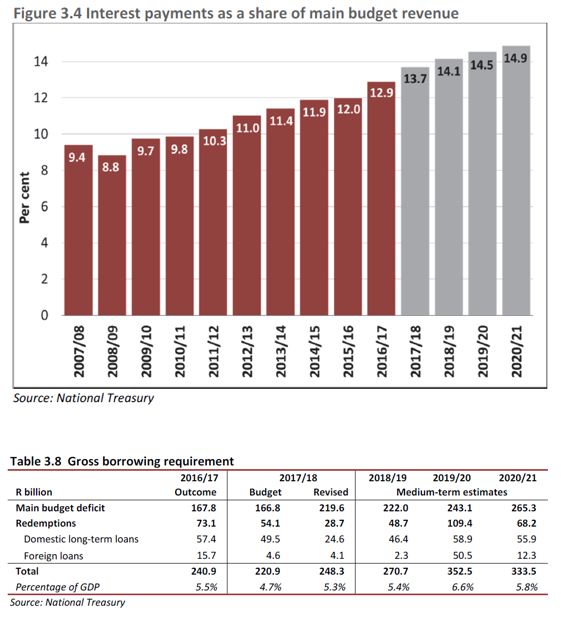

The government’s cost of raising funds for 10 years has risen by about 22 basis points (0.22 percentage points), while five year money has since become a quarter of a percent more expensive for the SA tax payer. The spread investors receive as compensation for the risk that SA may default on its US dollar-denominated debt has increased by approximately 13 basis points.

Given that SA, to the 2020/21 fiscal year, will have to raise about R1 trillion to fund the growing deficit and to roll over maturing debt, the Budget statement has been a very expensive failure for the SA taxpayer. Furthermore, by weakening the rand, widening the risks to our credit ratings and to the rand and by adding to the inflation rate, the prospects for faster economic growth have deteriorated.

Yet one has difficulty in understanding why the statement was so poorly received. The statement continues to commit the government to fiscal conservatism. That taxes collected were a very large R50bn less than estimated in the February Budget, was widely signaled, as was the breach of the spending ceilings incurred to keep SAA alive. Furthermore, the decision to increase the Budget deficit and the borrowing requirement, rather than raise tax rates, makes good sense in such dire circumstances.

The Treasury may be implicitly conceding that raising the income tax rates in February proved counterproductive. Higher tax rates have not increased revenues and have in all probability discouraged growth. Raising income tax rates in the near future may well have become less likely.

Strictly controlling government spending while selling government assets is the only way out of the debt and interest trap. But privatisation on any scale appears as unlikely after the Budget statement as it was before.

What then are the steps the SA government could immediately take that might raise confidence in the prospects for the economy, enough to encourage households to spend more of their incomes and for firms to add jobs and capacity to meet their extra demands? Confidence enough to lift growth rates closer to a highly feasible 3% rather than 1% a year?

What is essential is no less than a confidence boosting conviction that the SA government is capable of ridding the economy of those individuals who have gained destructive control of the commanding heights of the SA economy. It therefore takes more than a statement to improve the outlook for the SA economy and to escape the stagnation that makes sound budgeting so difficult. 27 October 2017