As published in the Business Day on 23 November 2018: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/columnists/2018-11-23-brian-kantor-retailers-give-thanks-for-black-friday–and-all-of-december/

It was Thanksgiving in the US on Thursday, a truly interdenominational holiday when Americans of all beliefs, secular and religious, give thanks for being American, as well they should.

This is a particularly important week for US retailers. They do not need to be reminded of the competitive forces that threaten their established ways of doing business. Nor do investors who puzzle over the business models that can bring retail success or failure.

The day after Thanksgiving is known as Black Friday, when sales and the profit margins on them will hopefully turn their cumulative bottom lines from red to black. It has been Black Friday all week and month and advertised to extend well into December. Presumably, to bring sales forward and make retailers less dependent on the last few trading days of the year.

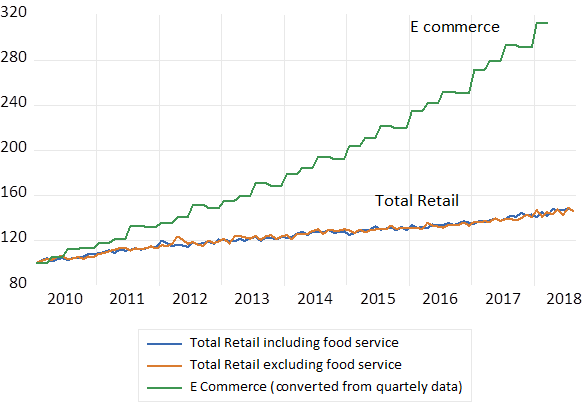

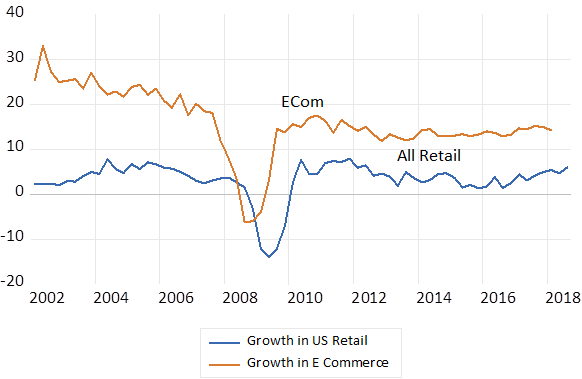

As we all know, competition has become increasingly internet- based from distributors of product near and far and yet only a day or two away. E-commerce sales have grown by over three times since 2010, while total retail sales including e-commerce transaction are up by half since 2010. Total US retail sales, excluding food services, are currently more than $440bn and e-commerce sales are over $120bn. The growth in e-commerce sales appears to have stabilised at about 10% per annum.

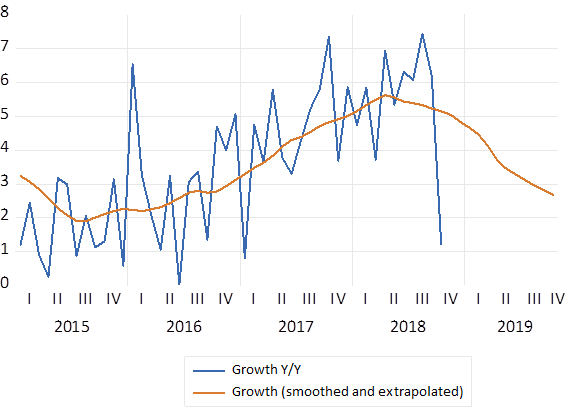

.jpg) Retail sales of all kinds have been growing strongly, though the growth cycle may have peaked. As may GDP growth, leading perhaps to a more cautious Fed. How slowly growth rates will fall off the peak is the essential question for the Fed, as well as Fed watchers, and answers to which are moving the stock and bond markets.

Retail sales of all kinds have been growing strongly, though the growth cycle may have peaked. As may GDP growth, leading perhaps to a more cautious Fed. How slowly growth rates will fall off the peak is the essential question for the Fed, as well as Fed watchers, and answers to which are moving the stock and bond markets.The importance of online trade is conspicuous in the flow of cardboard boxes of all sizes that overflow the parcel room of our apartment building, including boxes of fresh food from neighbouring supermarkets.

The neighbourhood stores of all kinds are under huge threat from the distant competition, which competes on highly transparent prices on easily searched for goods on offer, as well as convenient delivery. As much is obvious from the many retail premises on ground level now standing vacant on the affluent upper East side of New York. The conveniently located service establishments survive, even flourish, while local clothing stores go out of business because they lack the scale (and traffic, both real and on the web) to make a credible offering.

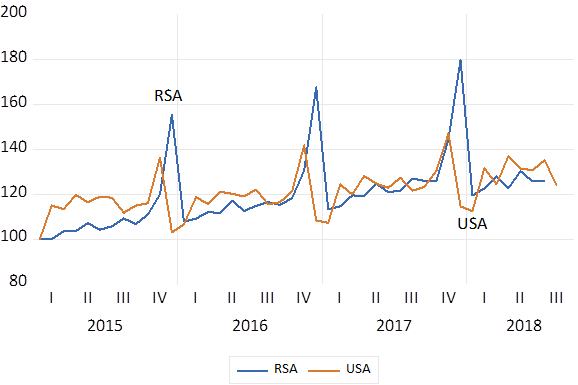

But spare a thought for SA retailers, for whom sales volumes in December are much more important than they are for US retailers. November sales for US retailers — helped by Thanksgiving promotions — are significantly more buoyant than December volumes. According to my calculations of seasonal effects since 2010, US retail sales in December are now running at only 90% of the average month, while November sales are well above average at 116% of the average month.

However, retail sales statistics in the US include motor vehicle and fuel sales, which are excluded from the SA stats. December sales in SA are as much as 137% above the average month, help as they are by summer holiday business, as well as Christmas gifts.

.jpg)

.jpg)