Listen to the Podcast: 10 Years after the crash

It’s a decade since the global financial crisis shook the world’s financial system. The policy response prevented a global depression, but in the process rewrote the textbook on monetary policy. Professor Kantor examines the crisis and the policy response – and then looks beyond, with particular lessons for South Africa.

The backdrop to the global financial crisis

The global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008-09 was caused by the collapse in the value of US homes, as well as the globally-circulated securitised and mortgage debt that had funded a long boom in US house prices. The value of an average US home had increased by an average of 9.2% per year between January 2000 and December 2006. By the time house prices bottomed in February 2012, the average home had lost 32% of its peak value of July 2006. US mortgages on the balance sheets of banks around the world – not only in the US – had lost much of their once-presumed secure value. As a result, much of the capital of the highly leveraged banks was wiped out.

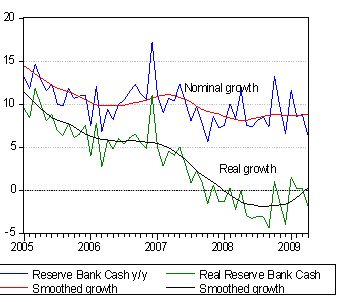

South African banks cannot flourish without a strong economy. Similarly, the economy cannot flourish without real growth in the supply of money and credit. Both have been lacking recently as we show in figure 1 , where we relate real economic growth to the real money and credit supply.

As was the case between 2003 and 2008, it will take a combination of better export prices, a stronger rand, less inflation, and lower short-term interest rates to spark the economy to a cyclical recovery. It will also take more encouraging economic policies for investors in SA businesses (less policy associated risks), including investors in SA banks, to permanently raise the growth potential of the South African economy. There is no reason to believe that South African banks would not be up to the task of funding a much stronger economy. What is required for both are higher returns on capital invested by banks and businesses generally: these would need to be risk-adjusted returns that would justify reinvesting earnings at a faster rate, and raising additional share and debt capital to sustain growth.

The price index of US bank shares peaked in May 2007 and troughed in September 2011, some 70% lower. Average house prices in the US regained their crisis levels by 2013, while the value of the average US bank share exceeded its value of September 2008 a little sooner. The values of both US banks and houses are now above their pre-crisis peak levels, though it took until 2016 or 2017 to get back to the heights of the pre-crisis boom (see figure 1 ).

The crisis for US banks has been long over, thanks to the bold and unprecedented interventions of the US Federal Reserve (the Fed), which pumped extraordinary amounts of cash into the banking system. The US Treasury recapitalised the banks, even those that it was argued didn’t need the helping hand. Europe took longer “to do what it took,” in the famous words of the chairman of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi, but largely succeeded in securing its banking system. The central banks and treasuries of Japan and the UK ran their own similar rescue operations.

South African banks were not directly exposed to the US mortgage market, although those with significant exposures offshore felt more of the draft. This was because the South African housing market held up well enough in its relevant rand value after 2008 to prevent any major write-downs of the value of the mortgage credit provided by the banking system. The price of the average middle-class house maintained its rand value after the GFC, while the fall in the value of the banks listed on the JSE was less severe than in the US.

South African banks and other financial institutions were, however, damaged collaterally by the collapse in the share prices of banks and financial institutions in the developed world. They were also damaged by sharp declines in the value of corporate and government debt, including South African government debt held on their balance sheets. The rand value of the JSE Banks Index declined by about 43% from its peak of April 2007 to its trough in February 2009 (see figures 2 and 3 in link ).

The impairment ratio of SA banks fell sharply between 2003 and 2007, but then rose sharply to ratios of about 2.4% to 2.8% of credit provided. These ratios have been more or less maintained since 2010.

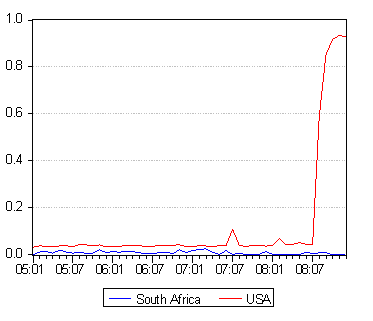

The South African Reserve Bank did not practice quantitative easing (QE), which are efforts to avert a liquidity crisis by pumping cash into the banking system through the purchase of government bonds and other securities in the market on a truly massive scale. Nor did the South African Treasury have to recapitalise the system by subscribing to additional share or debt issued by banks and insurance companies, as did the US government and the European Central bank.

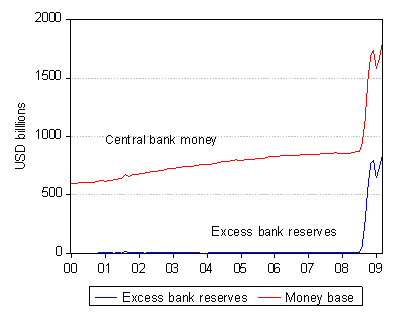

Much of the extra cash supplied to the banks of the US, Europe and Japan ended up on the asset side of their balance sheets as deposits with their central banks. The scale of these bank deposits with their central banks grew to be well in excess of the cash reserves they were required to hold against deposit liabilities. The extra cash supplied by central banks to their member banks was held as cash rather than used (as would have been usual) to fund bank loans or investments. Holding excess cash reserves that usually earn no interest is not profitable for banks, though the US Fed offered interest on these deposits. The other central banks do not do so, and the ECB charged banks to hold deposits.

The extra spending normally associated with additional cash supplied to banks thus did not materialise. This was because the extra cash supplied to the banking systems was closely matched by extra demands for cash. Inflation was restrained accordingly, in response to QE. Indeed, central bankers worried more about deflation than inflation after the crisis, a concern that encouraged still more QE until 2015. Only then did the Fed balance sheet stop increasing. A reversal of QE – reduced central bank holdings of assets – is still to transpire in Europe or Japan.

In figures 5 and 6 we demonstrate QE in action in the US. Note the increase in the size of the Fed balance sheet – from less than US$1 trillion in 2008 to over US$4 trillion by 2014. Note also the equivalent increase in cash reserves (deposits with the Fed) of close to an extra US$3 trillion – almost all of which were in excess of required reserves. Cash supplied by a central bank is described as high powered money because it leads to a multiple expansion of bank deposit liabilities (and bank credit on the asset side of the balance sheet of the banks). This is because the cash supplied to the banking system by the central banks is then loaned out by the banks and put to work by the customers of banks.[1]

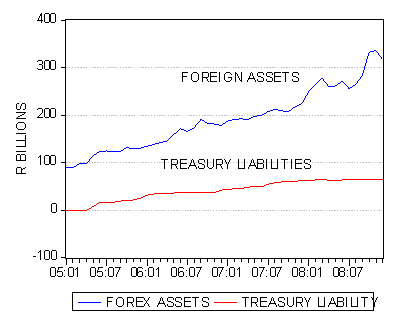

The contrast with South African banking developments over the same period is striking. The assets of SA banks declined very marginally after 2008, while those of the SA Reserve Bank increased at a steady pace. Moreover, the cash reserves held by SA banks, as normal, were held almost entirely to satisfy required reserve ratios set by the Bank. Excess reserves were kept at minimal levels while the commercial banks continued to borrow cash from the Bank – rather than supply more cash to the central bank, as has been the case in the US, Europe and Japan. It is of interest to note how much more dependent the SA banks have become on the cash they borrow from the central bank since the crisis. Currently, the liquidity supplied to the SA system by the Bank is of the order of R60bn. We return to a possible explanation of these SA trends below, where we consider trends in the equity capital ratios of SA banks.

The study can be found on my blog, www.zaeconomist.com. It is perhaps worth emphasising that it is not the supply of money, however broadly defined, that matters for the level of spending and so prices, but the excess supply of money over the demand to hold that money that can be inflationary.

SA and US economic trends before and after the GFC

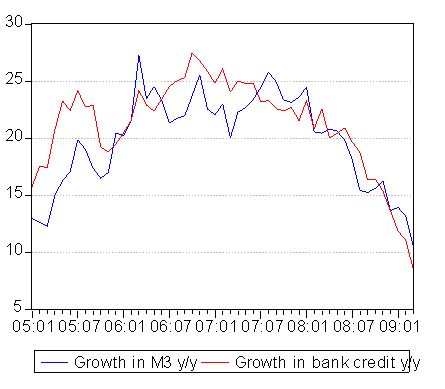

When comparing the developments in the US and SA before and after the GFC, it is relevant to note the very different circumstances that prevailed in the SA and US banking systems before (see figure 8 ). Between 2003 and 2008, SA banks were on a lending and money (mostly bank deposit) creation spree that accompanied and financed a period of rapid growth in the SA economy. This boom period has sadly not been repeated. Credit and money supply growth in the US, despite the housing boom, was more subdued at that time, though the temporary pick up in US money supply growth after the GFC should be noted. This response softened the blow of the recession that followed the GFC.

In 2006 at the peak of the bank credit cycle, bank lending in SA was growing at a very robust rate of over 25% per annum. Lending on mortgages had been growing at close to 30%. Mortgage loans can account for as much as 50% of all bank credit provided to the private sector in SA.

Such growth was regarded by the Bank as unsustainable and was then inhibited by significant increases in interest rates and borrowing costs. The slowdown in the growth in bank credit was therefore well under way when the GFC broke, as may be seen in the figures below . Hence it is difficult to isolate the impact on the SA economy of what was the end of a boom and the shock to the economic system that emanated from abroad. It is nevertheless clear that the GFC made any smooth adjustment to more sustainable growth in SA output, money and credit growth perhaps impossible, whatever might have been the reactions of the Bank.

The boom in money supply, the real economy between 2003 and 2008 and the subsequent

slow-down thereafter is demonstrated further in figure 10 below. While GDP growth turned negative immediately after the GFC, the economy soon improved and registered GDP growth of over 3% in 2011, with money supply growth rising from negative growth in 2009 to about a 10% annual rate by 2012.

The decline to sub 2% GDP growth rates occurred only after 2014, accompanied by a decline in the money supply and credit growth rates. It should be noted how rapidly short-term interest rates were allowed to fall soon after the GFC. They were increased in 2014 despite the persistent slowdown in GDP growth, which contributed to the higher interest rates.

In figure 11 we show exchange, interest and inflation trends before and after the GFC. The GFC brought with it a much weaker rand, and was preceded by higher inflation and interest rates. The recovery in the USD/ZAR exchange rate after 2009 was accompanied by much lower inflation and interest rates, resulting in the short-lived recovery in GDP.

The forces driving the SA economy, before and after the GFC

However, supporting these economic trends was the state of the global economy and the effect it had on metal and mineral prices that are so important for the balance of payments (including capital flows). It also had an effect on the direction of the rand and therefore, in turn, resulting in less or more inflation and so lower or higher interest rates. In figure 13 we show the key and related cycles of GDP growth trends, and those of the export and mining deflators.

The 2003-2008 boom was accompanied by improved mining and export prices. The downturn in the economy after 2008 was accompanied by a fall-off in mining and export prices. The GDP recovery after 2009 was accompanied by the revival of the commodity supercycle that ended in 2014. It is no coincidence that GDP and money and credit growth slowed so severely after 2014. The accompanying increase in interest rates added salt to the wounds of weaker commodity prices and the inflation that followed a weaker rand. The hope is that the recent recovery in the commodity price cycle, should it last, can help stimulate a recovery in GDP and credit growth.

SA banks: profitability and capital adequacy

Figure 14 shows the total assets of the SA banking system, the equity capital raised by the banks, and the ratio of equity to total assets between 1990 and 2018. The ratio of equity to total assets and liabilities of the banks rose through the 1990s. It peaked to about 27% in 2002 and then rose again with the GFC. The equity ratio has since declined and more or less stabilised around 17% of total assets and liabilities.

Figure 15 shows JSE-listed bank earnings and dividends per share and the ratio of earnings to dividends (the payout ratio). Dividends have been growing faster than earnings since about 2000 and the payout ratio (earnings/dividends) has declined consistently since the GFC.

Between 2000 and the GFC, annual growth in earnings averaged an impressive 19.1% a year. The best month saw growth in earnings of 45% and the worst saw earnings decline by 6%. Dividends grew at an average 18.4% a year, with the worst month recording positive growth of 5.5%. Since the GFC, JSE bank earnings have grown on average by 7.3% a year and dividends at a more robust 12%. The worst month for earnings growth, a decline of 27%, was recorded in February 2010.

Since 2012, bank earnings have grown at a steady 13% average annual rate and dividends at over 16%, though this growth has been declining with slower growth in the economy and in the pace of lending. The lack of demand for bank credit, and perhaps some lack of willingness to provide credit, has reduced the profitability of the SA banks and the case for retaining profits to fund growth. Additional reliance on cash borrowed from the Reserve Bank, noted previously, perhaps served a similar purpose to maintain generous dividend payments.

Conclusion – the future of the SA banks and the economy will depend on the returns to investing in SA

South African banks cannot flourish without a strong economy. Similarly, the economy cannot flourish without real growth in the supply of money and credit. Both have been lacking recently as we show in figure 17 , where we relate real economic growth to the real money and credit supply.

As was the case between 2003 and 2008, it will take a combination of better export prices, a stronger rand, less inflation, and lower short-term interest rates to spark the economy to a cyclical recovery. It will also take more encouraging economic policies for investors in SA businesses (less policy associated risks), including investors in SA banks, to permanently raise the growth potential of the South African economy. There is no reason to believe that South African banks would not be up to the task of funding a much stronger economy. What is required for both are higher returns on capital invested by banks and businesses generally: these would need to be risk-adjusted returns that would justify reinvesting earnings at a faster rate, and raising additional share and debt capital to sustain growth.

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Securities

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Securities