A shorter version of this essay was published in the Financial Mail (Special Edition 1959-2019) October 24th– October 30th 2019

A full version is available here: Understanding the past and future of the rand

A shorter version of this essay was published in the Financial Mail (Special Edition 1959-2019) October 24th– October 30th 2019

A full version is available here: Understanding the past and future of the rand

Developed and emerging markets have very different expectations of inflation. The monetary authorities should think carefully about the consequences of austerity

The developed world is much agitated by very low interest rates. Rates are so low that it is hard to imagine them declining further, so emasculating monetary policy.

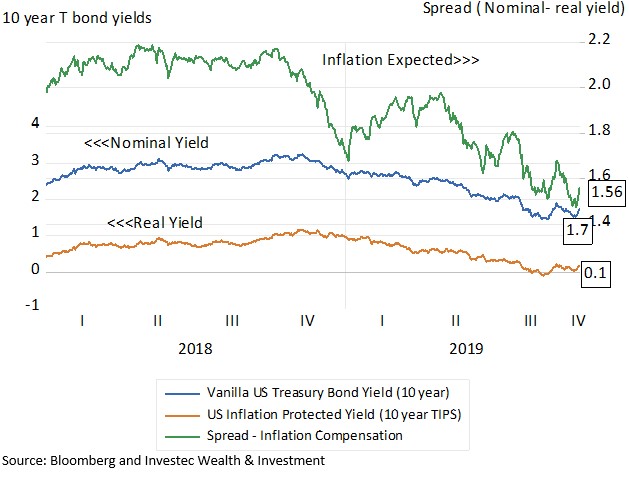

Interest rates reflect a relative abundance of global savings. Hence inflation (prices rise when demands exceed available supplies) is confidently expected to remain at these very low rates. Interest rates accordingly offer compensation for expected inflation. The US bond market only offers an extra 1.56% annually for bearing inflation risks over the next 10 years (see figure below).

The US Treasury bond market (10 year yields)

Deflation or generally falling prices, have rather become a threat to economic stability. When prices are expected to fall and interest rates offer no reward to lenders, cash (literally hoarding notes and coin) may be a desirable option. If prices are to be lower in six months than they are today, it may make sense for firms and households to postpone spending, including on hiring labour. Hence even less spent and more saved, compounding the slow growth issue.

An economy-wide unwillingness to demand more stuff is not a normal state of economic affairs. If demand is lacking, resources – land, labour and capital – become idle. In these unwelcome circumstances a government and its central bank can always stimulate more spending, including its own, without any real cost to taxpayers or economic trade-offs. More demand means no less supplied – therefore no output or income will be lost and more will be forthcoming, should demand catch up with potential supply.

Most simply, spending can be encouraged without limit by handing out money or jettisoning cash from the proverbial helicopter. For a government to be able to borrow for 30 years at very low interest rates is as inexpensive a funding method as printing money.

One can confidently expect unorthodox experiments in stimulating demand – should the developed economies continue to grow very slowly – and interest rates and inflation to remain at very low levels until growth and inflation picks up. Cutting taxes and funding a temporarily enlarged fiscal deficit with money or loans is another (better) option.

Quantitative easing (QE), the process whereby central banks create money to buy government bonds on a very large scale, mostly from banks, was highly unorthodox when first introduced to overcome the Global Financial Crisis of 2009. QE prevented the banks from running out of cash and defaulting on their deposit liabilities, thus preventing the destruction of the payments system that banks provide. But the banks, when selling bonds to their central banks, mostly substituted deposits at the central bank for previously held Treasury Bills and bonds. Bond holdings went down while deposits held by banks with the central bank went up by similar amounts.

The banks did not (much) turn their extra cash into loans. It would have been more of a stimulus to spending had the central banks purchased assets from the customers of banks (retirement funds and their like) rather than the banks. Had they done more of this, the deposits of the banks as well as the cash of the banks would have increased immediately. The growth in bank credit and bank deposit liabilities has remained very modest, especially in Europe, though the recent pick-up in growth in bank loans is noteworthy. Hence the persistently slow growth in spending in Europe.

Growth in bank loans in the US and Europe

Source: Thomson-Reuters, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Wealth & Investment

While the developed world struggles with low interest rates and subdued inflation and expectations of inflation, the world of emerging markets present very differently. Interest rates remain persistently high, with elevated expectations of inflation (and exchange rate weakness) to come. Accordingly, interest rates, after adjusting for realised inflation, remain at high levels as do inflation protected interest rates.

South African financial markets have continued to perform very much in line with other emerging financial markets. The JSE All Share Index gained about 2.6% in US dollar terms in 2019 (to 11 October) while the MSCI Emerging Market Index was up by 4.7% – both distinct underperformers when compared to the S&P 500, which was up by over 18% over the same period. The rand and emerging market currency basket had both lost about the same 2% against the US dollar over the same period (see figures below).

The USD/ZAR and the USD/emerging market currency exchange rates in 2019

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

The JSE and the emerging market equity benchmark in US dollars

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

On the interest rate front, emerging market local currency bond yields remain elevated – above 6% per annum on average for 10 year bonds. While the average emerging market bond yield has edged lower in 2019, SA bond yields have moved higher this year (see figure below). The market in SA bonds is factoring in more rather inflation and a still weaker USD/ZAR exchange rate. Unlike in the developed world, the cost of capital, that is the required rates of real return to justify expenditure on additional plant and equipment, remains elevated in SA. This means a continued discouragement to such expenditure and is negative for the growth outlook.

SA and emerging market bond yields (10 year)

Source: Thomson-Reuters, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Wealth & Investment

Capital remains very expensive for SA borrowers and growth rates remain subdued.

Interest rates and spreads in the SA bond market

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

A combination of more inflation expected with less inflation realised, because demand has been so subdued, has been toxic medicine for the SA economy. As in the developed world, the slack in the SA economy calls for stimulation from lower interest rates. And, unlike the developed there is ample scope for traditional monetary policy – in the form of rate cuts.

The inflation expected of the SA economy reflects the well-understood dangers of a debt trap and that the SA economy will print sometime in the future print money to escape its consequences. Yet fighting these expectations, which have nothing to do with monetary policy, with austere monetary policy makes no sense at all. Rather it means more economic slack, less growth, a larger fiscal deficit and enhanced inflationary expectations. Eliminating slack with lower short-term interest rates would do the opposite.

One of my pleasures is to listen in conference to the accounts of great business enterprises, as told by their CEO’s and CFO’s. They seldom fail to impress with their grasp of the essentials of business success in a complex world. One that always contains the threat of competition from close rivals and even more dangerous the disruption of their business models and their relationship with customers from quarters previously unknown. They are in it for the long run – not the approval of the stock market over the next few months. Short termism does not make for business success.

They sense the growing opportunity data collection and analysis offers to produce distribute and market their goods and services more efficiently. To scale the advantages of their intellectual property and culture, they must have global reach that inevitably includes managing successfully in China, with all its opportunities challenges and trade-offs. They are well aware of meeting the demands society and its governments may make on them for them to be able operate legitimately. They know they have to play by rules over which may have little influence.

And one senses from them a new urgency about a more disciplined approach to the management of shareholders capital. Business success and the performance of managers is increasingly measured by (internal) returns on capital employed, properly calibrated, that adds value for investors by exceeding the returns they could expect from the capital market with similar risks.

The business corporation is the key agency of a modern economy. The success of the developed world in raising output and incomes – improving consistently the standard of living is surely attributable in large part to the design that accords so much responsibility to businesses large and small. The improvement in the average standard of living, and of those of the least advantaged of the bottom quartile of the income distribution (helped by tax payer provided welfare benefits) in what we define as the developed world has been at a historically unprecedented rate over the last 70 years or so. While the rate of economic improvement may have slowed down in the past twenty or ten years it sustains an impressive clip. Over the past 20 years GDP per capita in constant purchasing power parity terms in the largest seven economies (G7) as calculated by the IMF has grown by a compound average 2.8% p.a. Over the past 10 years this growth rate has slowed only marginally to an average of 2.7% p.a. A rate rapid enough to double average per capita incomes every 26 years or so.

One might have thought that the proven capabilities and potential of the modern business enterprise would enjoy wide appreciation and respect. That is for its ability to deliver a growing abundance of goods and services that their customers choose, many of which thanks to innovations and inventions sponsored and nurtured by business that were unavailable or inconceivable to earlier generations. In so doing to provide well rewarded employment opportunities to so many and to provide a good return to their providers of capital – both debt and share capital. A large majority of whom, directly and indirectly, are not rich plutocrats but are the many millions of beneficiaries of savings plans, upon which they rely for a dignified retirement.

But this is not the case at all. Even for the commentators in the leading business publications who present a view of the modern economy and its dependence on the corporation as in deep crisis. A sense of grave economic crisis that given the much improved state of the global economy and of the role corporations play in it that is very hard to share for the reasons advanced.

For example Martin Wolf in an op-ed in the Financial Times (September 18 2019) Why rigged capitalism is damaging liberal democracy Economies are not delivering for most citizens because of weak competition, feeble productivity growth and tax loopholes

To quote Wolf’s conclusion on the reformed role of the corporation

“……They must, not least, consider their activities in the public arena. What are they doing to ensure better laws governing the structure of the corporation, a fair and effective tax system, a safety net for those afflicted by economic forces beyond their control, a healthy local and global environment and a democracy responsive to the wishes of a broad majority? We need a dynamic capitalist economy that gives everybody a justified belief that they can share in the benefits. What we increasingly seem to have instead is an unstable rentier capitalism, weakened competition, feeble productivity growth, high inequality and, not coincidentally, an increasingly degraded democracy. Fixing this is a challenge for us all, but especially for those who run the world’s most important businesses. The way our economic and political systems work must change, or they will perish.”

However much you might or might not share this view of the corporation, a state of being that is not at all apparent in the accounts of the threats and opportunities provided by business leaders- or in their actions as suggested earlier. Particularly when they are seen as rentiers given some guaranteed source of income provided by a conspiracy of protection against competitive threats. You might agree that he would have the leaders of the large modern corporation accept much greater responsibilities for the (apparently) failing human condition – responsibilities that are surely the essential purview of government. It is to ask corporations to achieve much more than they are at all capable of achieving to the satisfaction of society at large. It is to set them up for failure and to threaten the essential role given to them by society