South African savers dependent ontheir pension and retirement plans will have become aware that the actions of the Chinese Communist Party are sometimes more important than the actions or non-actions of the ANC. This is because of their likely large stake in a Chinese Internet giant, Tencent, held through their shares they own in JSE listed Naspers, (NPN) and via its controlling stake in Amsterdam and JSE secondarily listed, Prosus. (PRX)

Because of the much greater uncertainty about the policies the Chinese will apply to the Tencents, the Alibabas and Baidus and their like, a share in NPN or PRX has become much more risky to hold and therefore less valuable. Shareholders taking on more risk require compensation in the form of higher expected returns, this almost always means a lower entry price, a lower current share price.

The risk to any asset holder is simply the risk that the price of the asset they hold may rise or fall from its current level, should they have to or be forced to cash in their investment at some perhaps unknown point in time. The chances of a rise or fall from the current market determined price, assuming a well-informed active market in them, will be about the same 50% on any one day. Market prices follow a random walk, rising and falling in an irregular sequence. Hopefully these random movements come with an upward drift to bring actual returns in line with the higher expected returns, that make holding risky assets a rational choice for the long-term investor.

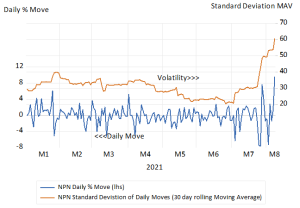

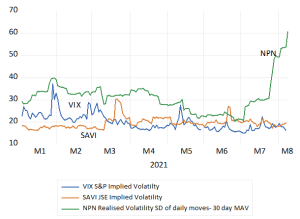

In riskier times the daily or hourly moves in both directions, up and down, become significantly wider, while the average move over any extended period will still stay close to zero. When the sense of the future becomes less certain, volatility of share prices increase, the standard deviation of daily moves about the average of almost zero widens, and the cost of insuring against such changes in market prices in the form of an option to buy or sell an option on the share or Index inevitably increases. As it has done in the case of NPN.

The recent increase in the daily volatility of NPN has been of extraordinary dimensions. Daily share price declines of 7% and then an increases of 10% on August 10th are truly exceptional and reveal how difficult it has been for well informed investors to make up their minds about what the future will hold for Tencent, NPN and PRX. The standard deviation of daily moves in the NPN share price (30 day moving average) has almost trebled since June 2021.

Daily % Moves in NPN and their Volatility Standard Deviation of Daily price Moves (30 day moving average of the Daily SD) to August 9 2021

Volatility compared; S&P 500 (VIX) JSE Top 40 SAVI and NPN Standard Deviation of Daily price Moves (30 day moving average of the daily SD) to August 9 2021

The rewards for holding on to your NPN or PRX shares remain to be seen. The China risks may decline to help add value. NPN management also hopes that the value of an NPN or PRX will be enhanced by the shares trading more closely to the market value of their Tencent Holdings. They are rejigging the allocation of its Tencent holding between Johannesburg and Amsterdam to attract stronger investor interest to reduce this discount to the sum of its parts, mostly Tencent.

My theory is that the value lost by shareholders is mostly because of scepticism about the value of the acquisitions and investments made by NPN/PRX. They are expected to return much less that the investors could earn for themselves taking on similar risks and so investors and analysts write down the value of this expensive investment programme when they estimate the value of NPN or PRX. The more invested, the more value destruction expected, the lower the value of an NPN or PRX share and the larger the discount. With the completion of the latest restructuring in sight we will see the alternative theories of the discount put to the market test.

The one possible for shareholders – if my theory holds – though it would be a bitter consolation, is that the lower the Tencent share price and the weaker the NPN and PRX balance sheets, the more disciplined and constrained will be their investment and borrowing programmes. And the lower the discount.