Many South Africans are condemned to a lifetime of inactivity for want of experience and the good habits acquired by having jobs. What are some of the practical steps that can be taken to solve SA’s unemployment problems?

In a well-functioning labour market, the number of employees who quit their jobs for something better will match those who are fired. The unemployed will then be a small proportion of the labour force. And it will not be a stagnant pool of work seekers. The number of new hires will roughly match the new work seekers, slightly more or less, depending on the state of the business cycle. Most importantly, the labour market will be reassigning workers to enterprises that are growing faster, from those that are growing slower or going out of business. It is a dynamic process that makes for a more efficient use of labour, and leads to faster growth in output and higher incomes from work over time.

To state the obvious, the above scenario does not describe the current state of the SA labour market. The unemployment rate since 2008 (the first year the current employment survey of households was released) and up to the just released for Q3 2020 survey, has averaged well above 20%. It was 23% in 2008 and 30.1% before the Covid-19 lockdowns. The army of the unemployed grew from 4.4 million in 2008 to 7.1 million in Q1 2020, compounding the problem at an average rate of 4% a year.

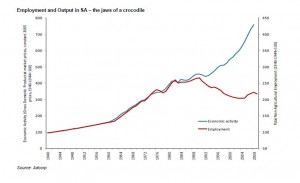

The numbers employed grew from 14.4 million to 16.4 million over the same period, at a 1.1% annual average rate, but therein lies the rub. The numbers of South Africans of working age who are neither working nor seeking work, nor are economically active, and therefore not counted as part of the labour force, numbered 15.4 million in Q1 2020. This is up from 12.74 million in 2008, having grown by 1.6% a year on average over the period.

The ability of the economy to absorb a growing potential labour force, defined as numbers employed divided by the working age population, now 39 million, declined from a low 45.8% in 2008 to 42.1% in early 2020. Even more concerning is the inability of the economy to absorb young people into employment. Of the 10.3 million between the ages of 15 and 24 years, 31.9%, or only 3.2 million, were working or seeking work. The economically inactive numbered 7.5 million. The absorption rate for the cohort fell from 17% in 2008 to 11% in early 2020. The economically inactive part of this group numbered 8.2 million in September. Of the cohort aged 15 to 34, the proportion who were not economically active was 40.4%.

A lifetime of inactivity

There is thus a large number of South Africans condemned to a lifetime of inactivity for want of experience and the good habits acquired on the job. What is going so very wrong in the SA labour market? We observe how vitally important it is for those with jobs to retain them. The struggle to hold onto well-paid jobs at state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as SAA and the SABC is an understandably bitter one with so much at stake. And the sympathies of the politicians are with the threatened workers rather than with the attempts to sustain the economic viability of these SOEs in the face of an ever more padded payroll.

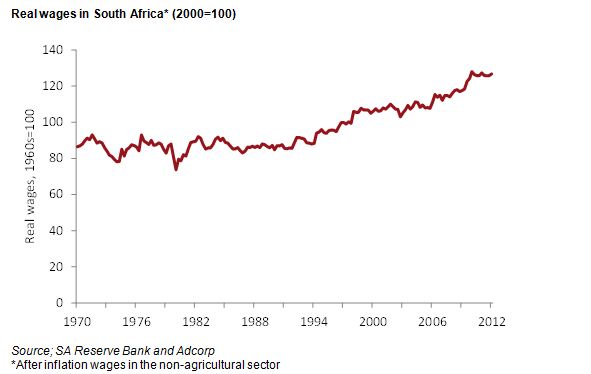

Being unemployed, especially for those retrenched form the public sector, is not part of a temporary journey to re-employment on similar terms. It is almost bound to be destructive of lifetime earnings. Even the competition authorities, who you might expect to focus on efficiency rather than job retention, make retaining jobs a condition for approving a merger or acquisition. Yet despite the large numbers of the unemployed and the economically inactive, the real earnings of those with jobs in the public sector have grown significantly and much faster than outside of it – by an average 2.2% a year after inflation compared with 1.52% for the privately employed. This perhaps explains why the SOEs have had such difficulty in balancing their books.

A system in SA has evolved that reinforces the better treatment of the insiders – those with jobs that are entrenched by law and practice – when compared with the outsiders who struggle. Many therefore give up the struggle to find “decent work”. A National Minimum Wage (NMW) is set at a level – R3500 per month – that regrettably few South Africans earn or are capable of earning. This is a major discouragement to hiring unskilled and inexperienced workers, particularly outside of the major cities. You would have to go well into the seventh decile of all income earners to find families with per capita incomes above this prescribed minimum wage.

It is possible to dismiss or retrench workers or managers in SA. But in addition to any regulated retrenchment package, it is not a low cost exercise to fire underperforming workers of all grades. Employers have to satisfy the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) to do so. Funding a human resources department, with skilled specialists well versed in employment and unemployment procedures, to whom dealing with the CCMA can be delegated, is one of the economies of scale available to big business. The small business owner-manager attempting to navigate the system is at a severe disadvantage that will surely discourage job offers.

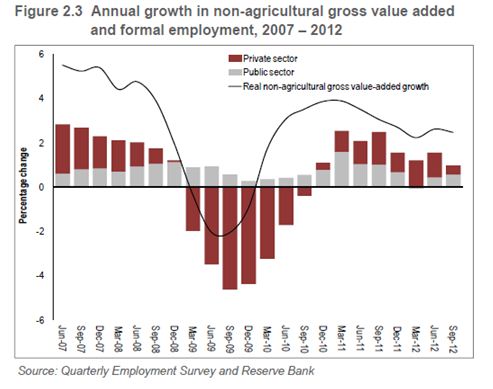

The impact of Covid-19

It is not just the regulations and practices that inhibit the willingness of employers to take on more labour. Post-Covid-19 reactions reported by the latest survey of households give some important clues to the forces at work. During lockdowns, numbers employed fell from 16.3 million in Q1 to 14.15 million in Q2, and recovered slightly to 14.7 million in Q3. The numbers counted as unemployed fell sharply from 7.1 million in Q1 to 4.3 million in Q2 and then rose to 6.5 million in Q3, after the lockdown. The numbers of those who were not economically active rose dramatically in Q2 from 15.4 million in Q1 to 21 million in Q2, when it made little sense to actively seek work. The numbers of the economically inactive then fell dramatically by over 2 million in Q3, as more people sought work and were physically allowed to do so.

The numbers employed in Q3 rose, but were not as many as those additional work seekers and so the unemployment rate picked up. It was a development highlighted in the survey. It made sense for more people to look for work because it was more likely to be found, and also presumably because the declining economic circumstances of the family, perhaps the extended family on which many depend, made the search for work and additional income imperative.

South Africans understandably have a reservation wage, below which working does not make good sense. It has to pay to work. And the economically inactive in SA who are overwhelmingly low or no income earners are presumably able to survive without work by drawing on the resources of the wider family. They will not have accumulated much by way of savings to draw upon. The family resources, on which they rely, are likely to be augmented by cash grants from government and from subsistence agriculture or occasional informal employment. Covid-19 may well have damaged the ability of the extended family to provide support for those not working or intending not to work, hence the fewer inactive members of the workforce.

The failure of SA’s mix of economic policies is revealed by what is still for many a reservation wage that remains higher than the wage employers are able and willing to pay them. Hence the discouraged employment seekers who are among the economically inactive. It seems clear that South Africans choose to some extent to supply or not to supply their labour, depending on their circumstances including their skills and earning capacity as well as the state of the economy. They have a sense of when it seems sensible to work or to seek work at the wages they are likely to earn.

Practical solutions

What can be done about this essentially structural issue for our economy? Businesses surviving Covid-19 have increasingly learned to manage with fewer workers and managers. Abandoning the NMW or the CCMA or reducing the legal powers of trade unions and collective bargaining would help increase the demand for labour, but this course of action is unlikely. Meaningfully improving the quality of education and training (on the job as lower-paid interns and apprentices) to raise the potential earnings of many more over their lifetimes of work, also seems wishful thinking. Reducing the value of the cash grants paid, so reducing the reservation wage to force more of the population to seek and obtain work, would be cruel and is as unlikely. Some form of welfare payments for work seems to be on offer in the form of the internship scheme announced recently by President Cyril Ramaphosa.

The Employment Incentive Scheme allows employers to deduct up to R500 off the minimum wage paid to workers under 29 and for all workers in the special economic zones. Employers simply deduct the subsidy from their PAYE transfers. It takes very little extra administration by either the firms or the SA Revenue Service. In 2015/16, 31,000 employers claimed the subsidy for 1.1 million workers and the scheme cost R4.3bn in 2017-18. The subsidy may well have to be raised to keep pace with higher minimum wages imposed on employers.

Raising taxes to subsidise the employment of young South Africans may be the only practical and politically possible way to provide more opportunities for them, especially if the market is not allowed more freedom to address the employment issue, by offering wages and other employment benefits that workers are willing to accept. Abandoning the NMW, the CCMA and nationwide collective bargaining agreements, all so protective of the insiders, would increase the willingness to hire and raise real wages for the least well paid in time. But it would be unrealisitic to expect the unemployment rate in SA to rapidly decline to developed market norms. It will take faster economic growth, which leads to higher rewards for the lowest paid and least skilled, to make work the better option for many more. And it will take many more workers to raise our growth potential.