The SA economy was in a holding pattern in the second quarter, helped by infrastructure spend, capital inflows and a sympathetic Reserve Bank

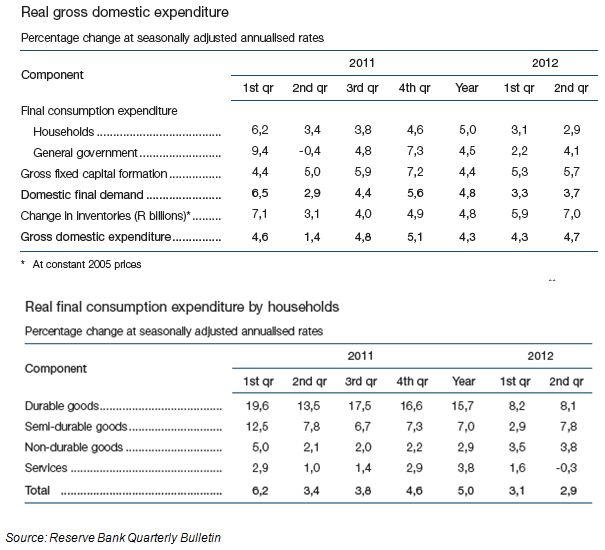

The SA economy did better on the demand side than it did on the supply side in the second quarter of 2012. Statistics on domestic expenditure, only now released by the SA Reserve Bank, complete the national Income accounts for the quarter. They show that Gross Domestic Expenditure (GDE) grew by 4.7 % in the second quarter at a seasonally adjusted annual rate – compared to GDP that grew at a 3.2% rate.

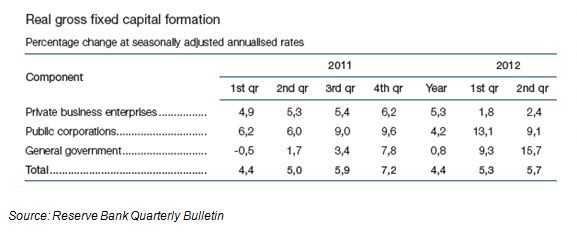

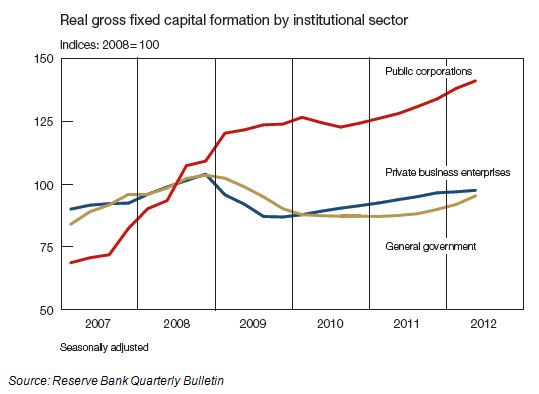

The fastest growing component of demand was Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) that grew by 5.7%. Households increased their spending on consumption goods by a pedestrian 2.9%, but household spending on durable goods (vehicles and appliances etc) and semi- durables (clothes etc) grew much faster than this while spending on non-durables (food) and especially services grew much slower: spending on services actually declined.

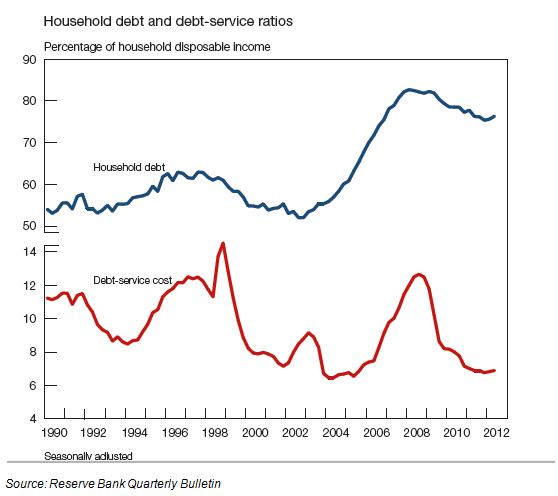

No doubt relative prices and, to a lesser degree, extra credit played a large part in these outcomes. Food and service prices rose faster than the prices of cars, appliances, clothes and perhaps especially services provided by municipalities. Consumers adjusted their spending accordingly, as they have been doing for some time. The Reserve Bank shows that the household debt to disposable income rose slightly after this ratio had fallen for an extended period. Thanks to lower interest rates, the debt servicing to disposable income ratio has stabilised at a very low 6%.

Where is the infrastructure spend?

This is a question often asked. The growth in spending on infrastructure is very apparent in the numbers. Capital expenditure by the government and the public sectors grew very rapidly in the quarter: by 9.1% pa and 15.75 pa respectively. Perhaps the impact is not easily seen or felt because of its high import content.

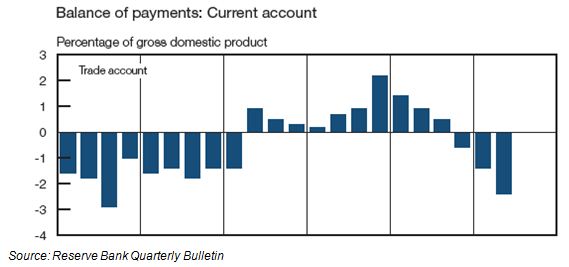

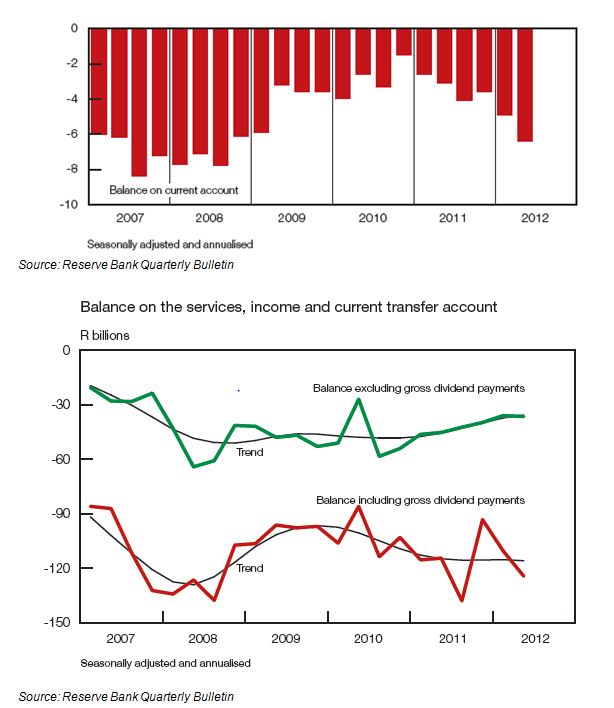

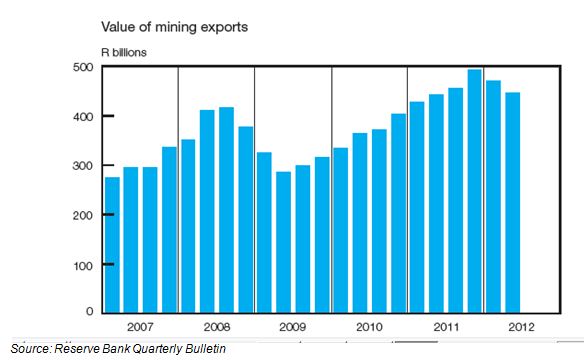

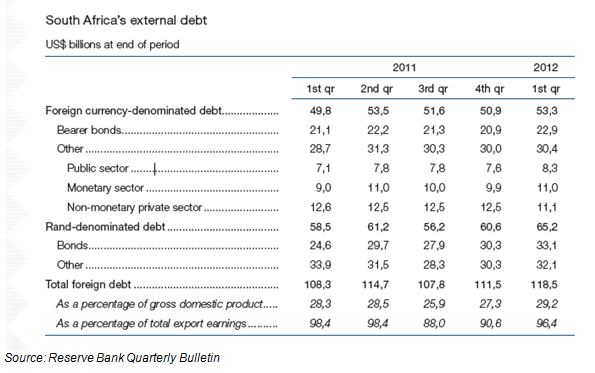

When spending rises faster than output, imports grow faster than exports and the balance of trade deteriorates. The major contributor to the very large current account deficit (which ran at a annual rate of over 6% of GDP in the second quarter) was a weaker trade balance. Export volumes nevertheless grew at a good rate of 5.9%, while imports grew even faster at a 9.7% real rate. Yet while export volumes grew strongly, prices for minerals and metals realised on global markets were less favourable, leading to a decline in rand revenues from the mining sector. Mining sector output in fact recovered very strongly from a low base in the quarter, so making an unusually important contribution to GDP growth in the quarter.

The outflows on the current account were fully matched by net inflows of foreign capital of R48bn. This is not a coincidence – it is much more like two sides of an equation. Without the capital the rand would have been much weaker, prices of imported and exported goods would have been much higher and demand for imports lower.

The economy would also have grown at a still slower rate without support from foreign investors. This makes the current account deficit and the accompanying capital inflows much more of an opportunity than the problem that it is so often and simplistically portrayed as. It is economic growth in SA that drives the returns on capital and the interest rates that attract foreign capital. Less growth means inevitably less capital attracted. Faster growth attracts more capital. Had growth in SA been even slower in the second quarter the current account deficit would have been smaller and capital inflows smaller. The rand might then have been even weaker (it lost 4.8% of its traded value in the second quarter, having gained 4.4% in the first) and inflation higher. These clearly would not have been desirable outcomes.

That much of the growth in imports was attributable to capital formation – which adds to the economy’s growth potential – is therefore helpful in attracting capital. Also helpful is that foreign currency debt issued by the SA government and the banks remains at manageable levels and has shown very little growth. A further helpful factor is that foreigners have shown a strong appetite for rand denominated debt, upon which default is technically impossible. Since there is no limit to the number of rands the SA government (via the Reserve Bank) could create to pay off rand debts, this demand for rand denominated debt represents a vote of confidence in SA’s fiscal conservatism and in the strength of its banking system.

The banks raised nearly US$9bn of rand denominated debts from foreign lenders between the first and second quarters. The private sector outside of the banks reduced their foreign debts over the same 12 months.

There are clearly upper limits to the liabilities SA and South African households and businesses can incur. What these limits are, are not known. Until they are known and a lack of foreign capital becomes an actual problem for the economy, it makes no sense to sacrifice growth for fear of reaching these limits. In fact slower growth would in all likelihood exacerbate, rather than help resolve any lack of capital inflow.

If the economy picks up momentum over the next 12 months (hopefully stimulated by faster global growth and higher export volumes and prices) returns on capital invested in SA business will improve and interest rates may well rise. These trends will attract foreign capital and the rand would very likely strengthen in what will be a more risk-on environment.

If the economy fails to pick up momentum in the absence of a recovery in the global economy, domestic demand will need and get encouragement from perhaps lower interest rates. A weaker rand would seem likely in such less hopeful circumstances. Should growth rates remain unsatisfactory over the next 12 months, the Reserve Bank is no more likely to feel restrained in its interest rate settings by the current account deficit than it has been to date. The best monetary policy reaction to the current account deficit or capital inflows is one of benign neglect. The Reserve Bank seems capable of ignoring the balance of payments. Brian Kantor