The failure to secure a large supply of vaccines to help South Africa to reach herd immunity quickly, reveals a vacuity in thinking about the cost to the economy.

The fiasco over the supply of vaccines reveals fully the vacuity of South Africa’s approach to Covid-19. The deposit of R283m to secure a supply of vaccines was not budgeted for because we didn’t have the money for it – even though money for much else was found in the adjusted Budget.

In this context, I observe that the Treasury deposits at the Reserve Bank amounted to R160bn in October, boosted by loans from the IMF and other agencies with anti-pandemic action front of their minds. Has anyone in the Treasury or government attempted to calculate how much additional income will be lost for want of the vaccine – and how much tax revenue the Treasury will not be able to collect?

It will be many times more than the R20bn to be spent on the vaccine. Bear in mind too, that R7bn of this is to be funded by members of medical schemes, which in effect makes it a tax increase or expropriation by any other name, unhelpful given the state of the economy.

Yet a supply of additional money could have been made available by the Reserve Bank, in the same way that money is being created on a large scale by central banks all over the world to fund the extra spending that the lockdowns have made imperative. And the Bank could still do so, to help the Treasury fund the vaccine and the money cost of rolling it out. The idea of raising taxes to fund the extra spending when the economy is under such pressure makes little sense. A higher tax rate or taxing specific incomes will slow the economy even further and might lead to lower tax revenues of all kinds.

Moreover, there is little prospect of more inflation to come. Should inflation emerge at some point, a reversion to normal funding arrangements would be called for. The danger then is that central banks like our Reserve Bank might not act soon enough and inflation picks up. But it is a danger that pales into insignificance when compared with the present danger posed by the pandemic.

Governments around the world know enough economics to know that spending more to help employ workers (and machines) who would otherwise be idle was a costless exercise – costless in the true opportunity cost sense. But South Africa seemingly cannot bring itself to think through the problem this way. The upshot is that South Africa lacks the essential self-confidence to do what would be right now.

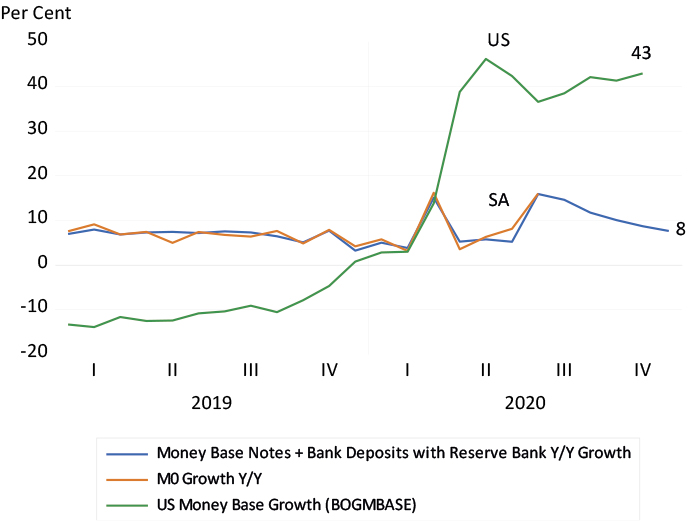

The monetary and financial market statistics tell us how unready the economy is to sustain any recovery of output and employment. The supply of extra Reserve Bank money in the form of notes and deposits by banks with the Reserve Bank, what is described as the money base or M0, rose by 8% in 2020. There was a flurry of extra such money in March and July 2020, since reversed. In the US, the money base is up by 43% (See figure 1).

Figure 1: Annual growth in central bank money, SA and US

Source: SA Reserve Bank, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and Investec Wealth & Investment

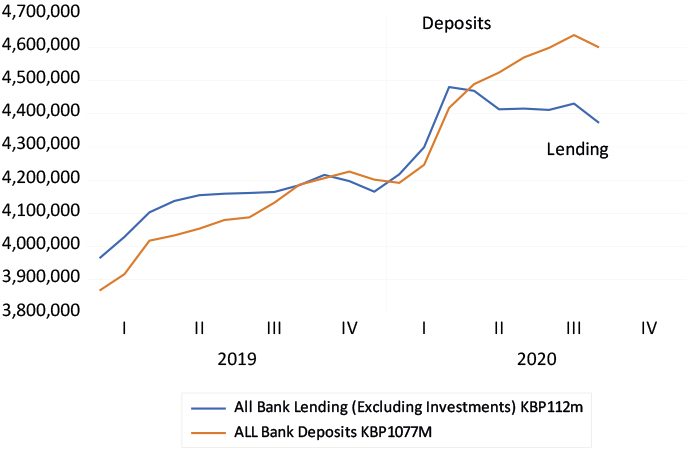

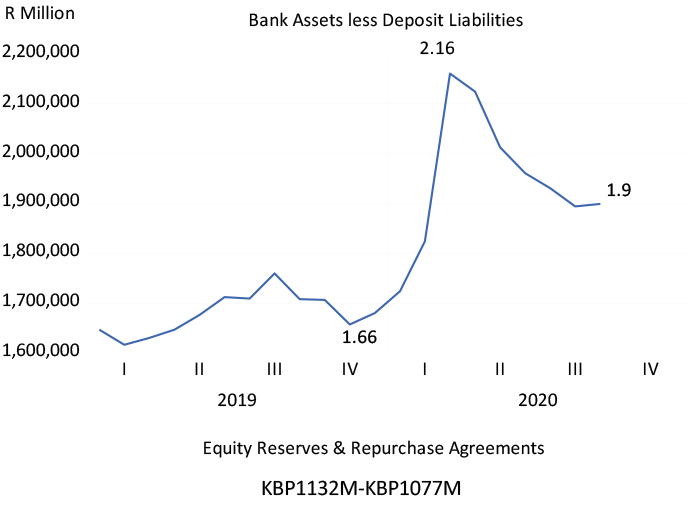

The SA banking system is hunkering down, not gearing up. Bank deposits have been growing at about an 8% rate, while lending to the private sector is up a mere 3%. The banks are building balance sheet strength, raising deposits and are cautious about lending more. They are relying less on repurchase agreements made with the Reserve Bank and other lenders, reserving more against potential bad debts while not paying dividends and hence adding to their reserves of equity capital. All of these act to depress growth.

Figure 2: SA bank deposits and lending (R million)

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment

Figure 3: SA banks – adding to equity capital

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment

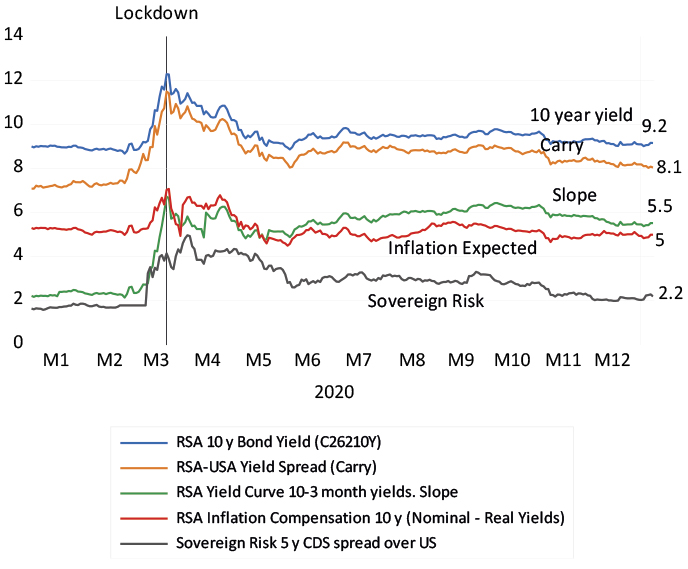

The financial metrics continue to paint a grim picture of the prospects for the SA economy. Long-term interest rates remain above 9%, even as inflation is expected to average 5% over the next 10 years. This makes capital expensive for potential investors who are therefore less likely to add to their plant and equipment. The difference between borrowing long and short remains wide, implying sharp increases in short-term interest rates to come and expensive funding for the government (that is taxpayers) at the long end. The risk of South Africa defaulting on its US dollar debt demands that we pay an extra 2.3% more a year than the US government for dollars over five years.

Figure 4: Key financial metrics in 2020-21

Source: Bloomberg and Invested Wealth & Investment

Poorly judged parsimony and monetary conservatism have brought SA great harm in the fight against Covid-19. They have made the prospects for a recovery in GDP and government revenue appear bleak. It is not too late to change course. We should be funding the extra unavoidable spending on the vaccine and its roll out by drawing on the cash reserves of the government or by raising an overdraft form the Reserve Bank.