What we already knew about the depressed state of the economy in Q2 2009.

We had been informed earlier by Stats SA that GDP, that is to say output growth, had declined further at a seasonally adjusted (-3.0%) annual rate in Q2 2009 for the third consecutive quarter making this a particularly severe recession. We also knew that the agriculture and particularly the manufacturing sector had suffered severe declines in production while mining sector output recovered showing positive growth for the first time in many quarters (See below). [Unless otherwise indicated all growth rates referred to in this report will be seasonally adjusted annual equivalent growth rates. All statistics and figures reproduced here are sourced from the Reserve Bank Quarterly Bulletin September 2009.]

The new bad news

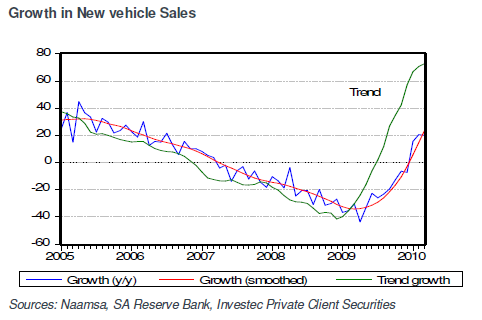

Not at all surprisingly we are now informed that aggregate spending on goods and services by households declined at a further very depressing (-5.8%) rate in Q2. The weakest component of household spending remained spending on durable consumer goods, including new cars (down -18.8% pa in Q2), which had suffered so much at the hands of the increase in interest rates through 2006, 2007 and 2008 that had continued long after such interest rate sensitive spending was in precipitate decline (See below).

Does income drive spending or spending drive incomes?

It will be said that the severe decline in personal incomes caused the decline in household spending. Both decline at about a negative 6% rate in Q2 (see below).

The reality is that the decline in household spending that constitutes such a large part (well over 60% of GDP) caused the decline in incomes. Expenditure in aggregate drives income and output as much as the other way round. The problem for the SA economy, as it has been the problem almost everywhere, has been a lack of demand, especially for exports, as global spending collapsed in the face of the financial crisis. Almost everywhere else very active attempts have been made to stimulate domestic spending and its corollary bank lending to compensate for the weakness of foreign demand.

SA had led itself into recession with severe monetary policy settings that undermined household spending and left the economy especially vulnerable to the weakness of exports after the crisis broke. And SA is surely almost unique in the reluctance of its central bank to reduce interest rates and ease quantitatively to encourage domestic spending. The obsession of SA monetary policy with inflation and inflationary expectations, over which monetary policy has little influence, has left the SA economy well behind in the economic recovery stakes.

The failure of monetary policy revealed

The failures of monetary policy are well revealed by trends in broader money supply and credit growth. Both are now in absolute damaging retreat.

This is a most unsatisfactory state of affairs which the authorities should be addressing urgently with all the means at their disposal, including purchases of foreign exchange to add cash to the system and generous and extended terms on which cash can be offered to the banks. Without a recovery in bank lending the weakness of household spending and the economy must persist. None of this central bank action has been forthcoming. As far as we can observe of foreign exchange reserves held by the Reserve Bank, little attempt has been made so far to inhibit unwanted rand strength. The very strong rand has been draining the competitive strength of domestic manufacturing, which is facing a large deflation of the prices of imported goods with which they compete and of export prices and volumes realised in weaker offshore markets.

It is the corporate sector that has become debt shy

The weakest part of bank lending has in fact proved to be lending to the corporate sector though lending to households remains weak with mortgage lending growing very slowly (See below).

Clearly the decline in corporate borrowing is the result more of a lack of demand by business for capital to expand output than an unwillingness of banks to lend.

The sort of good news

We can explain why SA business has so little demand for bank credit in current circumstances and why in part this may be regarded as good news in that it does portend a recovery in the economy. Spending on inventories in Q2 particularly by manufacturers of motor vehicles declined at an extraordinarily rapid rate in Q2. Real inventories are estimated to have declined by an annual equivalent volume of R52bn in Q2. This is equivalent to a 10% reduction in Gross Domestic Expenditure (GDE), which is defined as the sum of Consumption and Investment Spending plus the change in the level of inventories held by the business sector. GDE is estimated to have declined at an extraordinary -14.5% pa rate in Q2. Final demands (spending net of inventory changes) declined by only -3.5% pa helped by relative stability in capital formation (see below).

Capital formation by business is demand derived from household spending- both are very weak

Gross fixed capital formation held up supported by further strong growth in capital formation by public corporations and despite a sharp further decline in capex by the private sector (See below). The weakness in household spending has naturally undermined the willingness of businesses to add capacity. The decline in private sector investment spending together with the sharp run down in inventories has clearly reduced the demands for bank finance. Only a revival in household spending helped by increases in the supply of bank credit can get capital formation going again.

Slower growth has led to a surprising reduction in the current account deficit

That GDE (-14.5% pa) declined as much as it did relative to GDP (-3.0%), allowed total output (GDP) to exceed total expenditure (GDE) for the first time since the economy took off in 2003.

By definition the difference between GDP and GDE is the difference between exports and imports. For the first time since the economy took off in 2003 the economy ran a trade account surplus in Q2 2009 and surprised many (including the currency market) with a significantly reduced current account deficit. This more than halved in Q2 and declined from the equivalent of 7% of GDP in Q1 to 3.2% in Q2.

This deficit is about equal to foreign capital inflows. The current account deficit is the sum of the trade balance and the balance of interest and dividend receipts from abroad. SA is a net remitter of interest and dividends equivalent to about 3% of GDP (See below).

The good news, if it can be regarded as good news, is that exports declined by less than imports in Q2 2009 as we show below.

Less invested=less imported

The cut back in investment in capital goods and finished goods on the shelves and in the production progress took a full toll of imports. The good news about inventories is that they cannot continue this rate of decline and that a smaller rate of decline will add to growth rates to come.

Hoping for better news about faster growth and larger capital inflows

It would have been much better news had both exports and imports demonstrated the strong positive growth rates of much of the period since 2003. The growth in the SA economy since 2003 was willingly supported by net inflows of foreign capital, hence the debt service payments (See below).

As may be seen the capital continued to flow through the global financial crisis when they might have been thought particularly vulnerable to this heightened risk aversion. However the inflows have slowed down with the slower growth currently under way.

The current account deficit that rise with growth rates and the capital inflows that finance the sum of the trade and debt service accounts of the balance of payments are two sides of almost the same thing. The almost part is the usually very minor change positive or negative in foreign exchange reserves held by the banks, which solves the balance of payments equation. Therefore without the capital inflows the current account deficit would have to be smaller and the growth rates constrained. Without foreign capital inflows, growth would have been slower; however without the growth the capital flows would not have been forthcoming.

Growth self evidently leads capital inflows – fear of the balance of payments is harmful to the economy

The dependence of capital inflows to SA on growth in SA is now very apparent. The growth slowed down and the current account deficit and the capital inflows declined accordingly. It cannot be argued that it was withdrawals of foreign capital that forced a slowdown in the economy. The contrary is surely true: the self inflicted slowdown in the economy was accompanied by less foreign capital demanded and so supplied to SA borrowers. This was the case through the worst global financial crisis since the great depression of the 1930s.

Much less fear of the economic future called for

Thus it can surely be argued that if SA growth picks up, foreign capital will be forthcoming to help fund the growth. There is surely no reason to fear growth on the basis that it makes the economy vulnerable to the dictates of foreign capital markets. It was such fears that led to the excesses of monetary contraction in 2006-7 that eventually produced the recession of 2008. A more sanguine attitude to the balance of payments would have avoided such excesses of monetary policy zeal.

There is every reason to encourage growth in SA because it will lead to capital inflows. As has been pointed out by Governor Tito Mboweni, a current account deficit is not inflationary. Or in other words capital inflows fund imports that add to the supply of goods and support the rand and so help hold down prices. Hopefully such an understanding will help the monetary authorities engage actively in helping the economy recover. But even if the positive feed back loop between growth and inflation is not recognised the desperate state of the economy revealed by Q2 expenditure will surely bring the Reserve Bank in from the sidelines.