There was no good reason for the Reserve Bank to have surprised with a 50 basis point increase in its repo rate. There is in fact no good reason at all to subject the beleaguered SA economy to any further increases in interest rates. Given the bank’s own assessment of the state of the economy. To quote the statement of the Monetary Policy Committee of the 30th March. “Turning to inflation prospects, our current growth forecasts leaves the output gap around zero, implying little positive or negative pressures on inflation from expected growth”. The output gap is the estimated difference between potential growth in the economy (the supply side) and the growth in demand expected. The expectations for both growth in demand and supply are depressingly slow- no more than 1% p.a. over the next two years.. But clearly there are no demand side pressures on the price level.

The Bank’s forecasting model indicates that every 1 per cent shock to the repo rate will reduce GDP growth by 0.17% on an annual basis with the peak impact two or three quarters after the interest rate shock. While inflation is predicted to decline by 0.12% two years after the shock. While these are the estimated impact of higher or lower interest rates, other things equal, other things are very likely to change in highly unpredictable ways. For example exchange rates, or food prices or electricity tariffs or export prices- supply side shocks – over which the Reserve Bank has no control, nor any superior ability to predict. And which are as likely to move higher or lower over the forecast period and therefore should be ignored when setting interest rates. The strong focus of policy attention should be on the demand side of the economy- on the potential output gap over which the Bank does exercise influence. And without excess demand price increases cannot continue in an ever-higher direction- irrespective of recent inflation. Why the Bank would risk even slower growth by imposing still higher short term interest rates is hard to appreciate.

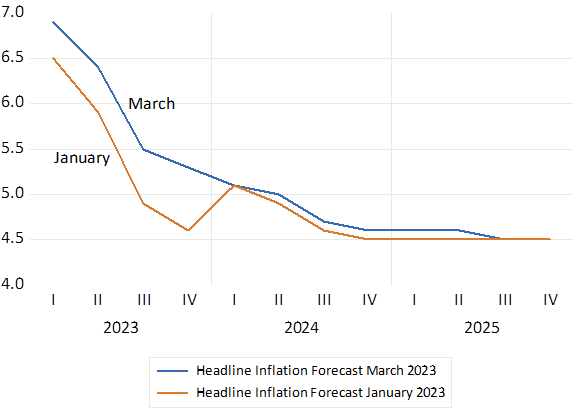

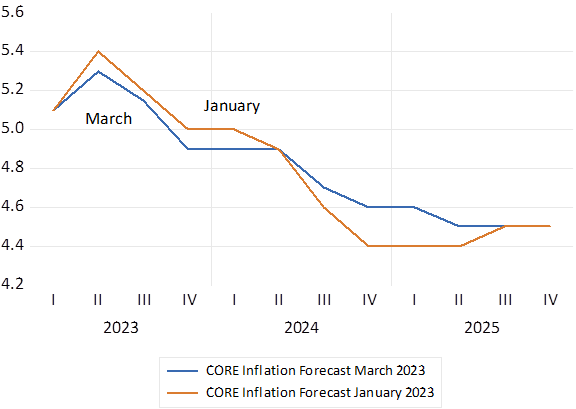

Since its January meeting the Bank, by no means alone, has been surprised by global inflation, by food prices, by rand weakness etc, enough to have taken recent headline inflation rates above what was predicted at earlier meetings. Though the longer term expected trend in headline inflation remains as it was – pointing distinctly lower below the targeted band. Incidentally the core inflation rate that excludes energy and food prices – large supply side shocks – has behaved almost exactly as expected. All further reason to have stood pat.

SA Headline Inflation. Actual and forecast by the Reserve Bank

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

SA Core Inflation. Actual and forecast by the Reserve Bank

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

There is perhaps more to the decision to raise interest rates than the usual focus on prices. The MPC statement and the Q&A session after the meeting cast unusual concern about the foreign financing needs of the SA economy. To quote the MPC statement again – “South Africa’s external financing needs are expected to rise. With a sharply lower export commodity price index, stable oil prices and somewhat weaker growth in export volumes, the current account balance is forecast to deteriorate to a deficit of 2.7% of GDP for the next three years. Weaker commodity prices and higher sate-owned enterprise financing needs will put pressure on financing conditions for rand-denominated bonds. Ten-year bond yields currently trade at about 11.2%, despite the expected moderation of inflation over the forecast period”

It therefore appears to me that higher interest rates to attract foreign capital interest rates may have played a decisive role in the MPC decision. The rand and the long end of the bond market did benefit from a wider interest rate spread in a modest way. But such experiments in exchange rate management are surely not to be recommended, given all else that can happen to exchange rates. I thought we have learned (expensively) to leave exchange rates and long-term interest rates to sort out balance of payments flows – and yet still to learn to set interest rates with the domestic economy front of mind.

RSA 10 year bond yields and the USDZAR – before and after the decision to raise the repo rate by 50 b.p.